Teaching may matter

Teaching Culture and Peace. Teaching May Matter

A case study: International Seminar in Hiroshima 2023

Mikael Søndergaard, Aarhus University

Ingrid Van Rompay-Bartels, HAN University of Applied Sciences

Fuyuko Takita, Hiroshima University

Introduction

Culture and peace are linked conceptually and historically. There has long been an assumption that knowledge and respect of other cultures promote peace, despite that war is an armed conflict to solve also culturally declined solutions, now (since war in Vietnam) broadly understood as “our way of life.” The link between culture and peace is, however, not straightforward.

Teaching, in a wide sense, has long been associated with efforts to facilitate our understanding in favor of peace. For instance, student exchange programs are historically linked to the aftermath of WWI and WWII as such programs started in 1919 and further expanded in 1946 (Bu, 1999). They assume that understanding various cultures is related to peace. The motivation of these exchange programs is that if you know by firsthand observation about the other culture, you should have a friendly rather than non-friendly relation with individuals from other cultures. Current armed conflicts in the Middle East and in Europe reminds us about other key variables at stake, too.

Understanding cultural competence and knowing and acting in foreign cultures with success is a longstanding interest in the fields of business and academia as a teaching method. These teaching methods have been systematically developed over many decades.

Various methods have been employed by teachers for students to gain knowledge, skills and attitudes that address cultural differences to achieve or maintain peace culture in the long term. For example, exchange programs offer in and out of classrooms experiences such as multicultural opportunities, the ability to interact with a diverse population, and provide students with full immersion in a foreign country for a continuous period of time.

Some parts of teaching cover culture and peace topics in a traditional classroom teaching. Insights via a mixed set of teaching methods offers experience and feedback on students’ participation with diverse populations within a controlled, simulated setting. One example of a simulation directly involving parties regarding the open conflict in the Middle East was developed by Bjørn Ekelund using students from Israel and Gaza working in teams (Ekelund, 2019; Ekelund, 2023).

Ekelund’s simulation is one example of highly developed and sophisticated simulation games that teach students hands-on experience and produce important reflections effectively by the participants. A widely used simulation in this category is Bafa Bafa (Bruschke et al., 1993; Köroğlu & Kimsesiz, 2023; Shirts, 1977).

Most participants report learning beyond a superficial level as a result of these simulations. Describing their experience as transformative, the students reported they learned a substantial amount after being brought out of their comfort zone. However, is this transformation something that occurred in actuality? This begs the question whether learning is acquired at a deeper level that eventually led to change that are reflected in students’ choices and behavior. And if so, how can we demonstrate such learning effects in a controlled, subjective measurement process?

A study shows that measuring learning effects of participants with a change in intended behavioral patterns when comparing pre- and post-simulation choice-making of the participants, based on questionnaire answers. Provided with well-designed feedback, changes in student behavior and choices were observed, which supports the intended teaching goals of making able to select a solution that fit the other culture in addition to increased cross cultural awareness (Heidemann & Søndergaard, 2022).

We learned from these simulations that post-simulation analysis along with participants’ transformational learning experience are the most rewarding parts since it allows us to connect theoretical tools with the participants’ experience.

However, that does not reflect participants actual learning experience through the simulation without proper subjective and controlled assessment and identified teaching goals.

When discussing peace and culture, changes in basic assumptions must be addressed. These changes are very difficult to measure as this requires a designed, controlled setting and more relevance that can be allowed in a purely laboratory setting.

We report on a study that succeeded in demonstrating these fundamental changes in students related to teaching goals within a seminar setting that focused on facilitating cultural studies and peace. Our study utilizes the BEVI analytical tool to facilitate a designed control setting regarding students’ change in growth pre- and post-seminar. The BEVI analysis was developed to help evaluate students’ values, beliefs, and behaviors before and after intercultural experiences and systematically compares the result (Shealy, 2004, 2015, 2016).

Focusing on an International Seminar that was held in early August 2023 in Hiroshima, Japan (commemorating the 78th anniversary of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in August 1945), student data was collected pre- and post-seminar and analyzed. This study examines how the attitudes of students changed significantly as a result, which is an important aspect relating to the teaching goals of the seminar.

The teaching method can be said to be in alignment with Galtung’s positive peace concepts (Galtung, 1969) since this International Seminar includes an A-bomb survivor’s testimony and intercultural interactions with students.

We find that teaching may matter. The teaching impacted the students at a deeper level illustrated by the change in students’ attitudes at most of the BEVI scales.

A Case Study of International Seminar in Hiroshima, Japan 2023

The Seminar

For a case study analyzing the effects of teaching with respect to culture and peace we use an International Seminar held annually since 2006 in early August. This established seminar focuses annually on varying global themes with high level of teaching methods and faculty members from around the world. Previously, student data from the same seminar was utilized in order to analyze patterns of learning during and post the recent pandemic in 2021 and 2022 (Søndergaard et al., 2023).

The context of time and location of this International Seminar draw the attention to the disastrous effects of nuclear weapons on people and the environment as well as the destructive sides of war. Using the history of Hiroshima, Japan, Japanese students and students from other countries engage in discussions about global citizenship and peace in order to understand that we are connected as citizens and that our challenges for a future with peace transcend geographical borders. In this sense the seminar facilitates Global Citizenship Education aiming to play an active role in building a peaceful, tolerant, inclusive, and secure society (UNESCO, 2023).

If culture and peace cannot be taught in such a powerful context such as the International Seminar held in Hiroshima, Japan, it cannot be taught anywhere else!

Teaching Goals of the International Seminar

Teaching goals reflect the idea of getting the students a working knowledge of being or becoming a global citizen in respect to peace, in particular. The seminar is designed to make the students see problems from a multidisciplinary perspective. During the seminar, efforts were made to discuss solutions to social economic and cultural challenges in the world. The 2023 seminar was designed to address climate issues, including energy, security, and sustainability, from multiple perspectives.

Based on the goals hoped to be reached by the seminar, the organizers of the seminar have an understanding the concept of global citizenship. This understanding rests on and develops from previously used concepts, such as cross-cultural competence and global mindset elements, which are contained in the following model.

Model

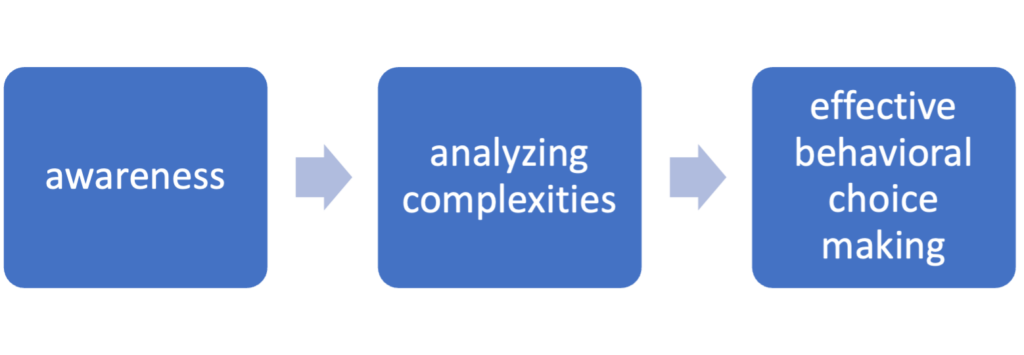

Classic dimensions of cultural competence are awareness of self and the other. The ability to take and navigate while regarding multiple perspectives is a learning outcome that is rooted in the standard global mindset understanding. In addition, as shown in the model below, awareness and complexity analysis seek to facilitate the development of cross-cultural settings and important interactions with individuals from other cultures effectively within the seminar. In other words, understanding awareness via analyzing complexities should lead to effective action.

The goals exceed the classic understanding of cross-cultural competence by including behaviors and actions. “Knowing” (knowledge) and “Doing” (action) are connected.

The seminar has teaching goals which are both rooted in the classic concepts of cross-cultural competence. However, this seminar builds upon these concepts, exceeding these teaching goals in an innovative way.

BEVI

We use BEVI, Beliefs and Values Inventory which is a suitable tool to evaluate teaching in international courses (Shealy, 2004). BEVI conducts surveys on participants’ same beliefs and values before and after a specific program seminar or course. Therefore, the BEVI tool is helpful to assess effects of teaching on changes in participants’ beliefs and values. We use BEVI scales to reflect the effectiveness of participants’ learning and the teaching purpose of the International Seminar. BEVI indicated reliable results in respect to a change of world view because of effective teaching practices in a seminar with students from diverse backgrounds (Grant et al., 2021).

International Seminar on Culture and Peace

The 2023 International Seminar continued focusing on U.N. related topics, teaching the understanding and skills in the practices of U.N. decision-making.

To achieve an understanding of the objective, content, and principles of peace education, a comprehension of how the concept of peace is approached and interpreted is essential. Galtung proposes a two-dimensional framework for understanding peace that distinguishes between positive and negative peace. (Galtung, 1996). Negative peace is defined as the absence of violence, while positive peace is understood as a state of social justice in which conflicts have been transformed constructively without the use of violence.

Feedback from students of the seminar indicates that the seminar was aligned with Galtung’s conceptualization of positive peace.

The reflection comments indicate that many students perceived that they had achieved their personal learning objectives during the seminar. For instance, one student shared that their perception of what they found most enjoyable about the seminar, which was in alignment with Galtung’s conceptualization of positive peace.

Our selection of citations aims at illustrating how the students noticed and reacted to the teaching goals of the seminar. Student feedback focused on answering what was found as the most enjoyable part of the seminar in relation to culture and peace:

The whole seminar has been enlightening. I’ve never been in this kind of situation before, with individuals from all over the world. Learning about cultural differences and similarities only added to the friendships made. Attending the peace ceremony was a humbling and powerful experience, one that I never would have envisioned. It’s one thing to learn about the impacts of war in a classroom, it’s another thing entirely to hear from survivors, see how a city has reacted, and view the museum telling stories of tragedy. The lectures and workshops too, are on completely different topics to my chosen discipline, but the most different ones I found the most interesting, as it was new and facilitated a deeper understanding of the planet we live on. I’m so, so grateful for this rich experience, and I believe I have developed my understanding as a result.

The reflections offer insights into the perceived outcomes in terms of academic knowledge, personal development, and cultural understanding. For instance:

The knowledge in peace, what is crucial for keeping peace (person-to-person communication and understanding of the history), what is critical in international conferences and overall communication, knowledge of UN, international law, culture, technology… I also learned my own personal quality that I might be good at pacifying a tense situation.

It can be reasonably assumed that the International Seminar has had some influence on the students’ worldviews, at least to some extent, because of their participation and engagement.

My time at the INU conference in Hiroshima has deeply impacted my perceptions of the world. Being surrounded by students and leaders from different backgrounds and cultures pushed me to challenge my own beliefs, while allowing me the opportunity to view complex topics through a different lens.

These examples of feedback presented here reflect subjective evaluations regarding quality and effectiveness of teaching methods in the event. By employing a BEVI-based analysis, it’s possible to gain a more profound understanding of the subjective learning effects that occur in a controlled setting.

BEVI ANALYSIS

The theme of the 2023 International Seminar was climate related topics in the world. The BEVI measured changes in students’ values and beliefs pre- and post-seminar. The BEVI global resonance dimension measured significant changes in students’ values by the end of the seminar. It was assumed that students possessed a high level of interest regarding this International Seminar’s topic—the environment—as they invested their time and resources to attend this abroad summer seminar.

Despite this assumption, the survey results indicated that this International Seminar had some effects on the students concern about climate change by the end of the program.

Changes on 17 BEVI Scales

| BEVI Domains | BEVI SCALES | MEASUREMENT | Significant Difference |

| Formative Variables | Negative Life Events | Difficult childhood parents were troubled; life conflict/struggles; many regrets | Yes |

| Fulfillment of Core Needs | Needs Closure | unhappy upbringing/life history; conflictual/disturbed family dynamics; stereotypical thinking/odd explanations for why events happen as they do or why things are as they are | Yes |

| Needs Fulfillment | Open to experiences, needs, & feelings; deep care/sensitivity for self, others, & the larger world | Yes | |

| Identity Diffusion | indicates painful crisis of identity; fatalistic regarding negatives of marital/family life; feels “bad” about self and prospects | Yes | |

| Tolerance of Disequilibrium | Basic Openness | open and honest about the experience of basic thoughts, feelings, and needs | Yes |

| Self-Certitude | strong sense of will; impatient with excuses for difficulties; emphasizes positive thinking; disinclined toward deep analysis (e.g., “You can overcome almost any problem if you just try harder | No | |

| Critical Thinking | Basic Determinism | prefers simple explanations for differences/behavior; believes people don’t change/strong will survive; troubled life history | No |

| Socioemotional Convergence | open, aware of self/other, larger world; thoughtful, pragmatic, determined; sees world in shades of gray, such as the need for self-reliance while caring for vulnerable others | yes | |

| Self-Access | Physical Resonance | receptive to corporeal needs/feelings; experientially inclined; appreciates the impact of human nature/evolution | Yes |

| Emotional Attunement | emotional, sensitive, social, needy, affiliative; values the expression of affect; close family connections | Yes | |

| Self-awareness | introspective; accepts the complexity of self; cares for human experience/condition; tolerates difficult thoughts/feelings | Yes | |

| Meaning Quest | searching for meaning; seeks balance in life; resilient/persistent; highly feeling; concerned for less fortunate | Yes | |

| Other Access | Religious Traditionalism | highly religious; sees self/behavior/events as mediated by God/spiritual forces; one way to the “afterlife” | Yes |

| Gender Traditionalism | men and women are built to be a certain way; prefers traditional/simple views of gender and gender roles | No | |

| Sociocultural Openness | Progressive/open regarding a wide range of actions, policies, and practices in the areas of culture, economics, education, environment, gender/global relations, politics | Yes | |

| Global Access | Ecological Resonance | Deeply invested in environmental/sustainability issues; concerned about the fate of the earth/natural world | Yes |

| Global Resonance | invested in learning about/encountering different individuals, groups, languages, cultures; seeks global engagement (e.g., “It is important to be well informed about world events. | yes |

Note BEVI scales derived from thebevi.com/about/scales.

Figure 1

The 17 BEVI scales offer insight into if participation in the seminar contributed to the development of the key goals intended for the seminar. Paired t-tests showed significant changes in the values indicated by the students before and after the teaching of the seminar, see figure I. Three scales (self-certitude, basic determinism and gender traditionalism) which reported no significant changes are not directly relevant to the 2023 International Seminar.

Figure II

In respect to developing an awareness of self and awareness of others, students’ answers in the relevant BEVI scales include ‘needs fulfillment’, ‘identity diffusion’, ‘basic openness’, ‘emotional attunement’, and ‘self-awareness’. These results reflect the effectiveness of the 2023 International Seminar’s teaching methods which has impact on students’ fundamental values and attitudes.

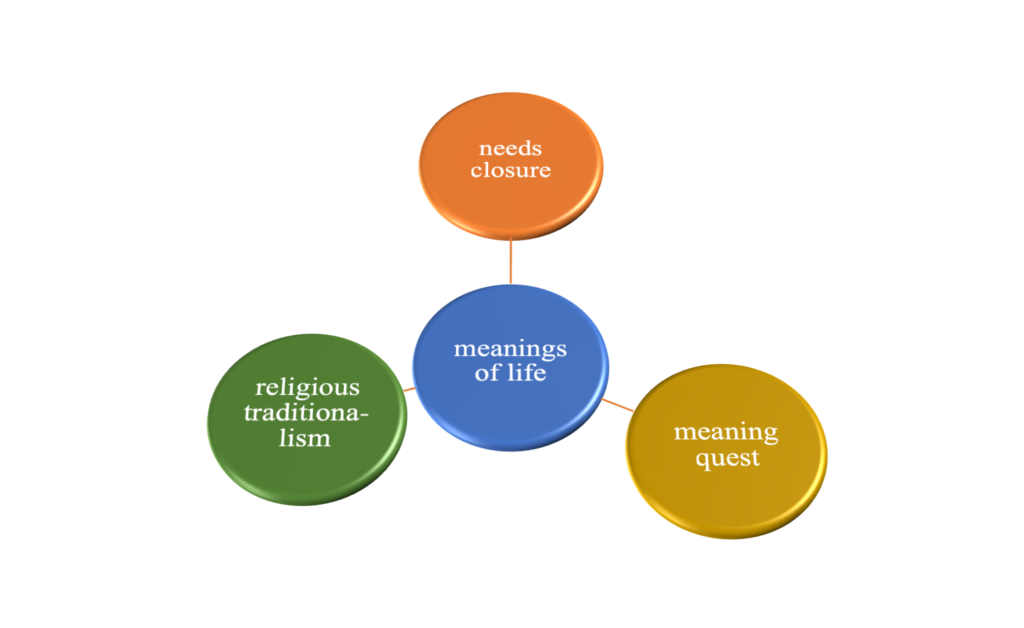

Through the seminar, students partake in complex practical training in analyzing situations with multiple perspectives. These actions, aimed at the relevant teaching goals, lead to significant changes in scores on BEVI scales. In particular, the BEVI scales of ‘needs closure’, ‘meaning quest’, and ‘religious traditionalism’ differed significantly at the end of the course compared to the scores taken at the beginning.

Figure III

In addition to the forementioned scales, students’ answers in the further parameters in BEVI of ‘effect of overall awareness’, ‘search for meaning’, and ‘concern for the unfortunate’, may present significant changes as a result of the Hiroshima atomic bomb victim’s testimony as part of the seminar. This testimony seemed to impact students’ overall awareness, value, and meaning of human life and suffrage, as indicated by the change in score within the BEVI parameter of ‘search for meaning’.

Likewise, in respect to the general theme of the 2023 seminar, students answered the BEVI scales of ‘ecological resonance’ and ‘global resonance’ differently at the end of the course. This indicates an increased awareness of the complexities of the climate issues presented in the seminar, relating to multilevel social, cultural, and political concerns.

Dimensions of Country Cultures and Peace

The teaching goals of the 2023 International Seminar assume a link between social values and global peace. This link was suggested for instance by Fischer and Hanke (Fischer & Hanke, 2009). A study demonstrates the link between different tools for country differences and attitudes toward peace related issues (Basabe & Valencia, 2007).

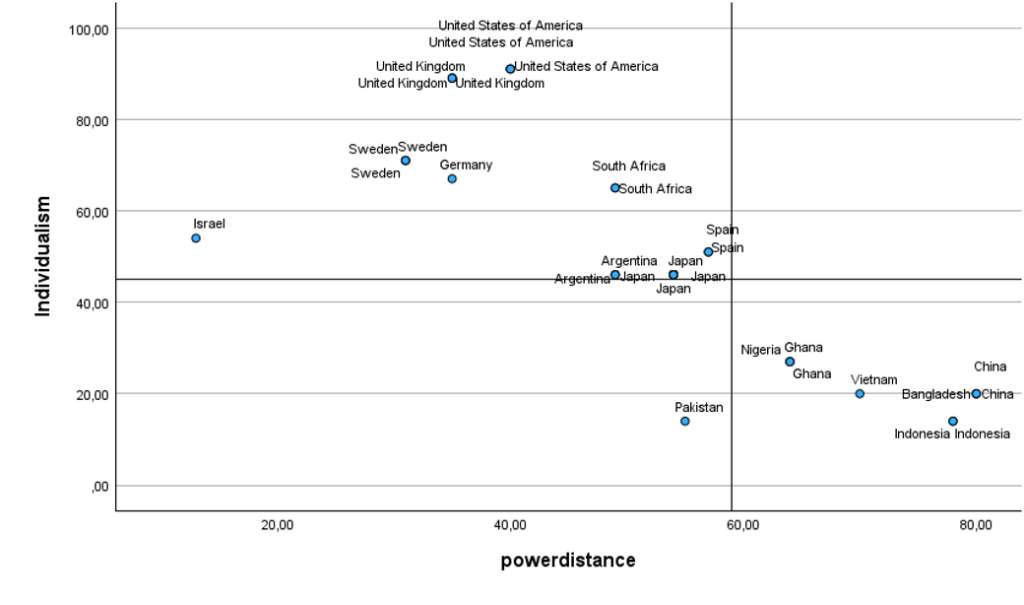

Differences in attitude regarding positive peace relate to the upbringing of the individual. The country’s cultural background of participants predicts the attitudes toward positive peace an individual may have. In this special issue of the Culture Impact Journal, Rieko Tashiro argues that people from countries with low power distance and high individualism relate differently to positive peace than peoples from high power distance and collectivist countries. (Tashiro, 2024)

35 participants in the 2023 International Seminar spent their primary years of upbringing in countries with low power distance and high individualism. Figure IV positions the two groups of participants.

The mean scores of the two dimensions are derived from the average score of all the countries with Hofstede’s dimensions.

Home country of Participants and Power Distance and Individualism

Figure IV

The group of participants whose background is associated with low power distance and high individualism consistently changed their attitudes towards a more positive stance on all BEVI scales. The changes in this group of participants are higher on the BEVI scales of sociocultural openness, ecological resonance, and global resonance—which are the most relevant scales in respect to the teaching goals of the 2023 International Seminar. See figure V

Figure V

This pattern of attitude changes may be indicative of their upbringing, where explicit communication of individual opinions and outlook is encouraged without concern for hierarchical roles.

On the scales of ‘negative life events’ and ‘needs closure’, these participants show large changes to a more positive stand. In contrast, on these scales a change to a more negative stand is shown by participants from a home country with high power distance and collectivist cultures, a hierarchicalmindset. See figure VI. In fact, the post-seminar scores of this group of participants indicate negative stances on five scales (i.e. negative life events, needs closure, identity diffusion, physical resonance, and basic determinism).

Figure VI

A limitation of this observation lies in the overgeneralization of participants’ behavior and beliefs between the two groups in the 2023 International Seminar. However, the findings may indicate that the home country background could predict different readiness and openness to change attitudes, regardless of an individual’s personal stance.

The focus of this study assesses the effectiveness of teaching goals and learning outcomes of the 2023 International Seminar. However, due to this study’s emphasis on particular dimensions such as BEVI analysis and student feedback, this study may not have fully explored the effectiveness of teaching goals and learning outcomes present 2023 International Seminar.

Therefore, a learning effect may also be an increased insight in attitudes held before the teaching took place. The learning effect that also facilitate an insight in own attitudes which may produce an even stronger and firmer stand in attitude that participants had before the teaching at the seminar begun. The role of group averages calls for including other instruments for a more complete understanding of the teaching effects.

Conclusion

Our case study of the 2023 International Seminar Hiroshima emphasizes the impact of teaching with real life world situations and promoting learner autonomy. Our study provides an illustrative example of Galtung’s principles of positive peace education.

Our findings indicate that the pedagogical approach during the International Seminar in Hiroshima has had a positive impact on students. Students’ feedback as well as BEVI assessment results support the effectiveness of selected teaching approach demonstrating that positive peace education may be taught effectively.

Teaching methods implemented in the program had a significant impact on the student participants. The findings of our study indicate that student’s attitudes changed on BEVI scales related to the goals of the seminar.

Furthermore, our results suggest that participants’ home country’s cultural values may influence their changes in attitudes, behaviours, and beliefs, as reported in the pre-and post-seminar BEVI surveys.

This finding suggests that further research should investigate how participants’ countries of origin and backgrounds affect changes in participants to understand the effects of teaching better. Our study is a big step towards understanding the intricate relationship between historical power context, teaching design, and quality and how such dimensions of teaching influence attitudes), as indicated by the BEVI analysis.

References

Basabe, N., & Valencia, J. (2007). Culture of peace: Sociostructural dimensions, cultural values, and emotional climate. Journal of Social Issues, 63(2), 405-419.

Bruschke, J. C., Gartner, C., & Seiter, J. S. (1993). Student ethnocentrism, dogmatism, and motivation: A study of BAFA BAFA. Simulation & gaming, 24(1), 9-20.

Bu, L. (1999). Educational Exchange and Cultural Diplomacy in the Cold War. Journal of American Studies, 33(3), 393-415. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27556683

Ekelund, B. Z. (2019). Unleashing the Power of Diversity. How to Open Minds for Good. . Routledge, Francis & Taylor.

Ekelund, B. Z. (2023). An Inclusive Language of Diversity. In Inclusive Leadership: Equity and Belonging in Our Communities (Vol. 9, pp. 121-131). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of peace research, 6(3), 167-191.

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by peaceful means: Peace and conflict, development and civilization. Peace by Peaceful Means, 1-292.

Heidemann, C., & Søndergaard, M. (2022). Systematic cross-cultural management education: a quasi-experimental analysis of guided experiential learning during intercultural simulations. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management(ahead-of-print).

Köroğlu, Z. Ç., & Kimsesiz, F. (2023). Use of Game-Based Teaching and Learning to Foster Intercultural Communication in English Language Education. In Handbook of Research on Fostering Social Justice Through Intercultural and Multilingual Communication (pp. 139-161). IGI Global.

Shealy, C. N. (2004). A model and method for “making” a Combined‐Integrated psychologist: Equilintegration (EI) Theory and the Beliefs, Events, and Values Inventory (BEVI). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60(10), 1065-1090.

Shealy, C. N. (2015). Making sense of beliefs and values: Theory, research, and practice. Springer Publishing Company.

Shealy, C. N. (2016). Beliefs, events, and values inventory (BEVI). Making sense of beliefs and values: Theory, research, and practice, 113-173.

Shirts, R. G. (1977). Bafa bafa. Del Mar, Calif.: Simulation Training Systems.

Søndergaard, M., Takita, F., & Van Rompay-Bartels, I. (2023). International Students’ Perceptions towards Their Learning Experience in an International Network Seminar in Japan: During and Post the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 15(11), 8641.

Tashiro, R. (2024). A Call for Many Peaces: The Power of Hibakusha Stories and Cultural Analysis of the Concept of Peace. Culture Impact Journal.

UNESCO. (2023). What is Global Citizenship Education? Retrieved 22 april

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge exceptional support of research assistant, Kylee Brahma, Hiroshima University