To build bridges, you must know where the shorelines are.

Huib Wursten. Author and consultant

Abstract

Worldwide trends like globalization, digitalization, climate, and energy transition are accelerating and deepening, strongly affecting our minds. We must tackle these urgent global problems by forming complex, adaptive coalitions.

But the definition of “we” is unclear. Instead there is fragmentation and polarisation between “Identity groups” originating from cultural and religious “clans.” Some of these groups feel neglected in liberal open democracies where the rule of law should prioritise equal rights and treatment. The need to be seen and recognized is a precondition to living in peace with each other. But parallel to this struggle, there is also an urgent call not to forget that there is a need to look into the future and solve the accelerating and deepening global problems. We are in this together.

This means that we should be able to define diversity in terms of real, existing differences. To cope with urgent global challenges, we need to know where the shorelines are before building bridges

In this article, 16 shorelines will be discussed. According to the author, these are mainly based on differences in country culture and personality. Some of the shorelines are the consequence of the interaction between Country culture and personality profiles

Keywords:

Country culture, Personality differences, Gravitational influence, Value preferences.

Introduction

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion are hot topics for organizations. International newspapers are writing editorials about this and CEOs worldwide are held accountable for putting this on the agenda. From a global perspective, it is clear though, that highly publicized issues in the USA, like Identity wars, White supremacy, White fragility, Woke and anti-Woke, are not the same as the issues in India, France, Nigeria, Germany, Japan or the Netherlands

National culture is an important cause of these differences. There are different “rules of the game” at work. This is analyzed in the paper on Mental Images and DEI programs.

In this paper, there will be an analysis of the meaning of the concept of diversity and the implications for Inclusion

Introduction:

The first question is: why is Inclusion important?

Three main answers:

-Democracy

Inclusion needs to be understood in the context of a functioning democracy. Democracy is not simply about “the will of the people”. It is about accepting that different groups have different interests and outlooks on life in every society. Democracy is about a system to “balance” diverse interests and find peaceful solutions for tackling problems. It requires that people from different groups feel represented.

-Sense of belonging

It creates a sense of belonging for individuals in various social and organizational settings. Inclusive practices recognize and value individual differences in culture, ethnicity, gender, age, ability, sexual orientation, and religion. By creating an environment that accepts and celebrates differences, Inclusion allows individuals to feel valued, respected and accepted for who they are, rather than being excluded or discriminated against. Individuals who feel included are likelier to engage in collaborative work and contribute to a positive work culture. Inclusion can lead to greater creativity, innovation, and productivity, as people with diverse backgrounds and experiences bring different perspectives and ideas to the table.

-We are in it together, but there is no we

At a Nexus web conference in March 2021, intellectual giants like Hariri, Kahneman and Thomas Friedman discussed what is happening in the world and what they expect about the future.

Friedman showed how trends like globalization, digitalization and the climate and energy transition are accelerating and deepening, strongly affecting our minds. This includes how algorithms influence our preferences and opinions through big data use. Friedman said we must tackle these urgent global problems by forming complex, adaptive coalitions.

Hariri was eloquently elaborating on how history is about storytelling, not just about the past but also about the present and the future. To him, storytelling adds meaning to the bits of information we get every second.

Kahneman was rather reluctant to make sweeping statements. Instead, he simply reacted to the first two speakers saying, ” There is no we.”

This is the heart of the problems. If there were an elected world government, all issues could be tackled with a consistent point of view. But there is no such centralized decision-making unit.

We see fragmentation and polarization between “Identity groups” originating from cultural and religious “clans.” Some feel neglected in liberal open democracies where the rule of law prioritizes equal rights and treatment. The need to be seen and recognized is a precondition to living in peace with each other. But parallel to this struggle, there is also an urgent call not to forget that there is a need to look into the future and solve the accelerating and deepening global problems. We are in this together.

Geert Hofstede warned against being too optimistic about achieving this feeling of “we are in this together” He famously said: “The survival of mankind will depend to a large extent on the ability of people who think differently, to act together.”

The challenges for “we are in it together.”

A recurrent theme in discussions of inclusion isism and discrimination against minorities. As professionals in cultural differences and their consequences, we are asked to give our opinion about coping with racism.

The only right answer is that we are against racism and discrimination and favor Inclusion. The complexity starts after this simple, principled answer. For instance, for whom is this relevant? The discussion is especially taking place in so-called “open democratic societies.”

An open democratic society is one whose laws, customs and institutions are open to correction by the continuous and free exchange of arguments and counterarguments among the societal stakeholders. This contrasts with a closed society based on revelations or a doctrine protected against falsification, rejection, or discussion.

An open democratic society cannot be culturally neutral since it emphasizes values regarding individuals’ equal worth and dignity. Therefore, open democratic societies have a value system in which the individual is at the core of moral thinking and behavior: Equal rights for all individuals and minorities.

Value diversity in this thinking is something to be practiced largely in such a way that it would not lead to any serious violations of the individual rights of others.

Citizens in open societies are expected:

- to accept other parts of the population as equals and

- not to close their eyes to racism and discrimination and

- to realize how much easier it is to be born as a member of a cultural majority.

A morality touchstone: Human Rights

To have a morality touchstone after the second world war, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was formulated to make it possible to have judgments about what is right and wrong. Again: the focus of all thinking about morality in this Universal Declaration of Human Rights is: All Individuals have equal rights. This also extends to minority groups. The formulation explicitly says that the rights are for everybody, not regarding color, race, gender, religious affiliation, and sexual preference. It is important to understand that 195 countries sign the declaration. As a result, in case of abuse, single countries can be held to account. Usually, this is done by naming and shaming.

Diversity

The usual way to define diversity in DEI programs is to relate it to gender, ethnicity, color, and sexual preference. However, lately, other elements are proposed to be considered: diversity of class, ideology and thought.

What does it mean if people talk about diversity.?

Frequently it is assumed that, in principle, people are the same everywhere.

For a long time, economists, psychologists, and sociologists based their arguments and findings on ‘evidence-based approaches’ without considering the origin and gender of the people in their samples.

Evan Watters concluded in ‘We aren’t the World’: “Economists and psychologists worked with the convenient assumption that their job was to study the human mind stripped of culture. It was agreed that the human brain is genetically comparable around the globe, so human hardwiring for much behavior, perception, and cognition should then be universal.)

In the last decade, the insight that these assumptions create a bias is gaining ground. Several examples can be found of either the problematic elements of these assumptions or research being done to discover or prove differences in gender, ethnic origin, or culture.

In the 2015 annual report, the World Bank Group states that a more behavioral approach would be more effective than the purely economic approach based on the assumption that people act rationally and self-interestedly.

The report argues that a more realistic account of decision-making and behavior will increase the effectiveness of (development) policies.

In this report, three main principles are recognized and used to build a framework:

- People think automatically. This means ‘intuitive, associative, and impressionistic. The automatic system is ‘the secret author of many choices and judgments you make’. This automatism creates the possibility of making fast and efficient decisions.

- People think socially. Humans are social beings and tend to comply with their social environments. This also means they are interested in others’ welfare and not exclusively their own. Therefore, they are willing to work and cooperate.

- People think with mental models. To deal with the vast amount and complexity of information in their environment, humans create and use categories, schemas and ‘taken-for-granted’ worldviews to understand and cope with all kinds of situations. The social environment and institutions enhance and shape people’s thinking and the alternatives they can imagine. Over time and history, these mental models become ‘internalized,’ These thinking patterns with corresponding assumptions about the world and fellow humans seem ‘natural’ and inevitable even though other possibilities, perceptions, and interpretations might exist and be available. These ‘mental models’ seem to be vastly shaped and influenced by the cultures of humans.

In the world bank report, the above notions lead, among others, that the way information and decisions are framed influences the effectiveness of interventions.

In international organizations, the importance of understanding cultural differences in values, communicational styles and “ways of doing business” has been recognized for quite a while, instigated and influenced by thinkers and researchers such as Geert Hofstede.

Since then, the insight that cultural factors are important for understanding the world has increased.

Even stronger, people are getting aware that culture has a “gravitational influence “on behavior in general, including ideas about diversity. In an interview with the “Economist”, Hofstede pointed out that the discussions about diversity tend to ignore the consequences of national culture and to be too superficial and positive about the sustainability of the diversity consensus.

He said that culture is more often a source of conflict than synergy. Cultural differences are a nuisance at best and often a disaster.”

This, of course, needs further clarification. Also, the role of personality differences will be discussed.

National culture as a source of diversity

The Hofstede dimensions of culture (Hofstede2001, Hofstede, et al. 2010) represent a well-validated operationalization of differences between the cultures of present-day nation-states as manifested in dominant value systems.

Five elements are of utmost importance for understanding that culture has a gravitational influence on behavior:

- The definition of culture is about the collective “programming” of the mind that distinguishes one group or category of people from another.” This definition stresses that culture is (1) a collective, not an individual attribute; (2) is not directly visible but manifested in behaviors; and (3) common to some, but not all people. We are talking about the preferences of most people most of the time; (4) – it is about subconscious preferences. Most people are unaware of their programming.-

- The cultural dimensions are the outcome of factor analysis. They represent the fundamental issues all human beings everywhere must cope with; Country culture is about how nations differ in their coping approach.

So, the dimensions are not a random collection of factors that emerged from haphazard situations; instead, they reflect the basic value dimensions.

- The dimensions are evidence-based by repeated research, validated over 50 years, with regular repeats trying to falsify the outcomes.

- Cultural differences are determined by how the dominant majority in different countries address those issues. So we are talking about the central tendency in a bell curve.

- Each country has a ‘score’ on each of the fundamental dimensions, reflecting the central tendency. The scores go, in principle, from 0 to 100. These scores, in turn, provide a ‘picture of a country’s majority culture. Hofstede’s approach is clear, simple, and statistically valid.

By this set of 4 value dimensions, it is possible to describe how culture, in a decisive way, defines diversity. But please remember, we are talking about central tendencies. Not about individuals.

The four confirmed value dimensions as shorelines:

- Small Power distance versus Large Power distance

Power distance is the extent to which less powerful members of a society accept that power is distributed unequally. People in countries scoring low, like the US, Canada, the UK, Scandinavia, and the Netherlands, are likely to accept ideas like autonomy, empowerment, decentralization, participative decision making and flat organizations. Business schools worldwide tend to base their teachings on low power-distance values.

Yet, most countries in the world have a large power distance. In Large power-distance cultures, people accept existential hierarchy and centralized decision-making.

- Individualism versus Collectivism

In individualistic cultures, Individual rights and obligations are the center of value preferences. People believe in Universalistic values. The rights and obligations are (or should be) valid everywhere. The rule of law guarantees human rights.

In collectivist cultures, people belong to in-groups who look after them in exchange for loyalty. The value orientation is particularistic, applicable to people of the in-group

Identity is based on the social network to which one belongs. Therefore, the score on IDV affects the thinking about equal rights.

Collectivism is a value system that emphasizes the importance of group identity and the collective good over the rights and interests of individual members. In collectivist societies, the needs and goals of the group are prioritized over the needs and goals of the individual, and the group is expected to work together for the common good as formulated by the top people. In Individualistic cultures, people identify more as members of voluntary social groups than members of clans.”For collectivistic societies, it is difficult to accept that individuals have the right to decide about moral issues. Religious institutions and their officials represent the traditional values, and they are the only ones in the position to “weigh” new developments like freedom of sexual preference and equal rights for women. It is not a coincidence that Putin, as leader of a huge collectivist country, is legitimizing his actions by saying that “we embody the forces of good in the modern world because this clash is metaphysical” and “We (the Russians) are on the side of good against the forces of absolute evil…. This is truly a holy war that we’re waging, and we must win it and of course, we will because our cause is just. We have no other choice. Our cause is not only just, but our cause is also righteous, and victory will certainly be ours.” Sergey Karaganov, connected to Russian President Vladimir Putin, predicted that democracy is failing and authoritarianism is rising because of democracy’s flawed moral foundations. An interesting case here is the refusal by the captain of a Dutch soccer team to wear a rainbow armband at a time the Football Union supported actions to promote gay rights. This captain from a Turkish-Dutch family publicly said it was about his Islamic religious beliefs. Many Dutch commentators reacted negatively by saying he should make his own decisions and understand he is a role model. What was not understood is that in his “in-group,” a Turkish migrant family, the religious in-group he belongs to is the reference and starting point for morality. The key element is that in return for loyalty to the in-group, the in-group takes care of the members. Group convictions determine the preferences of individuals. Individuals should be in harmony with the in-group’s thinking and interest.

Of course, this should not be understood in an absolute way. All human beings are, in principle, gifted with empathy. Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. It is a crucial component of human relationships and is often seen as a key aspect of human morality and compassion. Based on a shared competence for empathy, one can say that universal human rights are rights that are inherent to all human beings and are not dependent on nationality, race, ethnicity, religion, or any other status. Human rights include the right to life, liberty, and security of person; the right to education and employment; and the right to a fair trial. But certainly, there can be tensions between collectivist and individualist perspectives on human rights. As discussed above, proponents of collectivism argue that the group’s needs should take precedence over the individual’s rights. Empathy can play a role in mediating these tensions by helping individuals to understand and feel the emotions and experiences of others.

- Masculinity versus Femininity

In masculine cultures, competition, achievement, and success are dominant values. The dominant values in feminine cultures are consensus-seeking, caring for others, and quality of life. In masculine cultures, sympathy is for the achiever. Status symbols are important to show success. Feminine cultures have a people orientation. Sympathy is for the underdog, “small is beautiful,” and status is less important.

Hofstede research on culture and Frans de Waal among non-human primates.

Hofstede found that Gender scores are identical for three confirmed basic value dimensions. The exception was Masculinity versus Femininity. He found that everywhere in the world, women scored somewhat lower than men on average. For a full understanding, American women score, on average, lower than American men, but American women are much more masculine than Swedish men. The other way around: Swedish men score more Masculine than Swedish women. But Swedish men are much more culturally Feminine than American men. This has strong political consequences. The more feminine a culture is, the more sympathy goes to the underdogs and “have-nots.” So there is, in principle, support for redistributing tax money to help the unfortunate.

Frans de Waal looked at the nature of the role of biological sex and the nature of gender in humans by looking at the behavior of non-human primates. He observed that in the other primates, too, you can speak of gender because they learn certain aspects of their sexualities from each other. For example, the young males watch the adult males and the young females watch the adult females and follow their example. There is also a cultural transmission of how you behave as a male and female. In that sense, gender is a concept that can also be applied to other species. There is evidence that there is biased learning going on. For example, research on orangutans in the forest showed that young females eat exactly the same foods as their Mothers. But young males vary. They sometimes eat foods that the mother never touches. That’s because their models are the adult males they see eating occasionally.

De Waal makes a few points:

“There is as much gender diversity in other primates as in humans. Homosexual behavior is very common in primates. I usually call bonobos “bisexual” because I don’t think they make a big distinction between whether they have sex with a male or female. All the gender diversity that we have in human society, transgender people and homosexual orientation, and so on, we can see in the other primates. The interesting part is that they have no trouble with it. I’ve never noticed that they exclude an individual because of this. The tolerance level is a lot higher than in most human societies. But the variation is very similar.” Sex is mostly binary: 99% of individuals are either male or female and there’s a small slice of individuals in between.

There are universal sex differences, which we see in all human and primate societies. It’s very hard to argue with some biological background. For example, all young males and primates (including human boys) like to wrestle when they’re young; they like mock fighting, running around, and trying to wrestle each other down. In the young primates, this is a very big bias; the males like to do that, and the females don’t necessarily like to do that. That’s why females often play separately from males. Another thing that’s universal in play behavior is that young females are more interested in infants and dolls in primate and human societies. If you give a doll to a group of chimps, a female will always pick it up and care for it. If a male picks it up, he may take it apart and look inside the doll to see what’s in there. But the females will put it on their belly and back, walk around, and care for it. They do the same thing with the infants of other females. The interest of young females in infancy is also a universal human bias, primate bias, and it’s fairly logical because later in life, they will care for offspring for most of their lives.

Biology or culture? People want to choose between biology and culture. And that’s why you get these discussions with people who say gender is all cultural. There is nothing that is all cultural. That doesn’t exist. Because what is culture? Culture is us influencing each other and we are biological organisms, biological organisms affecting other biological organisms—automatically, biology is in there. There is no pure culture. It doesn’t exist. There is no pure biology either. That doesn’t exist. And that’s why, in biology, we don’t speak about instincts anymore in animals, because everything an animal does is influenced by how it grew up and what it learned in its lifetime, and so on. And so there is no pure biology either. So people want to choose between the two. And they have a false sense of security that they can do that, but you cannot. And so everything we do is influenced by two factors, the environment and our genes, and by the interaction between the two.

Masculinity and Femininity is a cultural construct. De Waal: “I usually divide it not by male and female but by masculine and feminine and everything in between. It’s an extremely variable concept. And as I said, it’s probably applicable to other primates, though maybe less well than in humans. But in humans, it is very important to distinguish those two. Gender has to do with how you express your sexuality, your sex role, and how much you follow or don’t follow the dictates of your culture.” But there is a flexibility that can also be seen in the other primates. De Waal gives the following example, “chimpanzees and bonobo males, they don’t do anything with the young. The females do everything. The males may occasionally protect them, but that’s all they do. But we know that if a mother loses her life in the forest, and suddenly there is an orphan, we know that sometimes males pick up these orphans and carry them. They adopt them and not just for a couple of days. High-ranking males, like alpha males, may adopt a baby chimp and take care of it for five years. It’s not always expressed, but they have that tendency and that capacity.”

Biased learning. Hofstede talks about subconscious learning. De Waal explains it by biased learning: it is aroused more by familiar and similar individuals. In humans, that means individuals of your culture, language, color, etc. We do empathy studies on all sorts of animals nowadays and they always have this social bias built in, which means it’s hard to generate empathy for individuals who are quite different from you, who are distant, who are a different ethnic group, or speak a different language. Then it becomes more difficult for you. But the fact that we have it is really important. And once you have empathy, the capacity for it, you can try to expand it mentally, to expand the rules for in our human moral systems. That’s a cognitive capacity that we have and that’s why we try to do things like that.

- Weak versus Strong Uncertainty avoidance

Uncertainty Avoidance is the extent to which people feel threatened by uncertainty and ambiguity and try to avoid these. In cultures of strong uncertainty avoidance, there is a need for rules, procedures, and formality to structure life. Decisions are taken after considering all available information. As a result, there is a tendency for deductive reasoning and a strong belief in experts. In weak uncertainty-avoidance cultures, people are motivated by making quick decisions based on limited information. As a result, they tend to prefer inductive reasoning, and there is a belief in “best practices” as formulated by practitioners. Experts are frequently seen as “Academic.”, which is not meant as a compliment.

Shorelines because of personality: The Big Five

Since 1980 research has been published about the defining characteristics of personality. This created possibilities for exploring the relationship between culture and personality. The Five-Factor Model of personality is a universally valid taxonomy of traits, applicable regardless of society, ethnicity, gender, age, or education. Furthermore, the factors are stable over most of the adult lifespan; self-reports generally agree with observer ratings that the five factors and the more specific traits that define them are strongly heritable (McCrae & Costa, 2003).

The five factors create the next shorelines in defining diversity:

5. Openness to experience: Openness reflects the degree of intellectual curiosity, creativity, and a preference for novelty and variety a person has.

People who score high on this trait tend to be more liberal or left-leaning in their political views. They are more likely to support progressive policies, such as gay marriage, drug legalization, and environmental protection

6. Conscientiousness: (efficient/organized vs. easy-going/careless). Tendency to be organized and dependable, show self–discipline, act dutifully, aim for achievement, and prefer planned rather than spontaneous behavior.

People who score high on this trait tend to be more conservative or right-leaning in their political views. They are more likely to value tradition, order, and stability and to be skeptical of change.

7. Extraversion: (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved). Energy, positive emotions, assertiveness, sociability and the tendency to seek stimulation in the company of others, and talkativeness. Extraverted people tend to be more dominant in social settings than introverted people, who may act shy and reserved. There is less clear evidence for a connection between extraversion and political preferences. Still, some studies have found that extraverts are more likely to be politically active and identify as liberals.

8. Agreeableness: (friendly/compassionate vs. challenging/detached). Tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic towards others. People who score high on this trait tend to be more empathetic and compassionate and are more likely to support policies that help others, such as social welfare programs. They are also more likely to be politically liberal.

9. Neuroticism: (sensitive/nervous vs. secure/confident). Tendency to be prone to psychological stress. The tendency to experience unpleasant emotions easily, such as anger, anxiety, depression, and vulnerability. Neuroticism also refers to the degree of emotional stability and impulse control and is sometimes referred to by its low pole, “emotional stability”. People who score high on this trait tend to be more anxious and insecure and are more likely to support authoritarian policies and be politically conservative.

Interaction between Culture and Personality

It is important to see that the research by McCrea and others shows that personality traits are biologically based dispositions that characterize members of the human species. This is a clear difference from the research on culture. Here the emphasis is on subconscious learning.).

In an interview with Psychology Today (Poghosyan, 2017), Hofstede compares the interaction between the two with a jigsaw puzzle: “You could compare culture and personality to a jigsaw puzzle and its pieces. A jigsaw puzzle is made of different pieces, just as all personalities within a culture are different. But all together, they make up one puzzle and not another puzzle. Consider their personality if you want to know something about people (for example, their behavior). But if you want to know something about their society (for example, what is tolerated in the neighborhood), that has more to do with culture. Societies are made of individuals, and culture makes an imprint on the individuals who are born there. The first ten years of our lives are very important. That’s when you get your basic mental programming and acquire characteristics you call culture.

Looking at the Jigsaw puzzle, more shorelines can be defined.

- Orientation towards truth. Two cultural elements are important :

Type of Religion: a difference is found in comparing monotheistic religions with polytheistic religions. Going back to belief in one holy book and one Creator (an Unmovable mover) in Islam, Christianity and the Jewish religion, people of these religions believe in a truth that is one and individable. On the other hand, in Polytheistic belief systems and philosophies of life like Hinduism, Shintoism, Confucianism and Buddhism, people think that truth depends on time, context and situation.

The score on Uncertainty avoidance. Low UAI means a willingness to make quick decisions based on available information. The emphasis is on Inductive thinking. Pragmatism is the dominant school of thought with revealing expressions like: truth is when it works, and: the proof of the pudding is in the eating. High UAI makers that people want to avoid risks by gathering as much information as possible before decision-making. The emphasis is on Deductive thinking and Intellectualism. Expressions: “Du choc des opinions jaillit la Verité” (From the clash of opinions, springs the truth), etc.

Some shorelines are related to the jigsaw of culture and personality:

- Conservative versus a progressive mindset. Next to value preferences as a result of culture this is a difference found in all cultures. However, the consequences are stronger in Masculine cultures because of the tendency to polarize.

- Economic/political thinking: Do you believe in the invisible hand of the market and see Governments as a threat? Or do you believe in “Central steering” by Governments? The scores on power distance and Uncertainty Avoidance are relevant here. In high Pewerdistance cultures, people see central steering as an existential phenomenon

- Ethical orientation: “ethics of conviction” versus “ethics of responsibility” The German sociologist Max Weber introduced this famous distinction between two types of ethics: “Gesinnungsethik” (“ethics of conviction”) and “Verantwortungsethik” (“ethics of responsibility”) “Ethics of conviction” means that people act according to principles and tend to disregard potential consequences. ”Ethics of responsibility” means that people work according to what they believe will be the likely consequences of those actions

- Human rights versus traditional religious/cultural ideas: Can we allow individuals to decide about moral problems? Or should we refer to religious and cultural traditions’ moral status?

Example 1: Abortion rights: pro-choice (individual) or pro-life (God’s will) Example 2: Putin: the metaphysical fight against the decadent (LGBTQ+) West. - Empathy only to people like us versus empathy for unfamiliar people. Despite all ideals, discrimination remains a frequent hidden or open poison in open societies. The question is why the discussion about prejudice and racism against black people is at the center of attention. In an interview, a simple answer is given by two anti-racism fighters: “Anti-black racism concerns the people who, based on their African roots or cultural background, are getting disadvantaged treatment. For a big part, this originates from the colonial past., the history of being enslaved. As a result, black people are confronted with ethnic profiling and job discrimination”. The enslavement history makes blackness still seen as negative and inferior, while white or Caucasian stands for intelligent and civilized. Despite all ideals, racism is still a stubborn challenge in open societies. Mostly, it comes in three shapes: as a bias or stereotype. But also by applying statistics to make judgments about individuals. The difference between a bias and a stereotype. A bias is a personal preference, like, or dislike, especially when the tendency interferes with the ability to be impartial, unprejudiced, or objective. If you hire a Caucasian for a job with an equally qualified black applicant because you think blacks are not as smart as Caucasians, you are biased. A stereotype is a preconceived idea that attributes certain characteristics (in general) to all the members of a class or set. If you think that all Asians are smart or white men can’t dance, that is a stereotype. You find one characteristic true; you assume them all true. Example: In some cultures, like in Morocco, it is seen as impolite to look the boss in the eyes. Stereotype: “All Moroccans are unreliable; they don’t look you in the eye

Or this one:

The difference in emphasis on equality or diversity. The belief that the responsibility for poverty lies with the poor and deprived themselves and that poverty and inequality are moral rather than political issues has deep historical roots and continues to shape public policy today. Neo-liberalism with leaders like Thatcher and Ronald Reagan presented poverty as an individual failure rather than a social problem. Even as societies and institutions have become more diverse, many have also become more unequal. Debates about inequality have increasingly tended to look at equality in terms of “diversity”. The observation is “When you ask them for more equality, what they give you is more diversity,” “But a diversified elite is not made any the less elite by its diversity.” (Walter Benn Michaels, Adolph Reed, Jr) Reed and Michaels insist on the centrality of class in any discussion of social inequalities. They stress that the emphasis on diversity results from the fact that many groups faced discrimination and were excluded from positions of power and privilege. The drive for greater diversity is seen as a push for greater equality and an attempt to dismantle exclusion barriers. Equality and diversity are, however, different issues. While societies and institutions have become more diverse, many have also become more unequal. Michaels and Reed are clear: Diversity policies do not necessarily challenge inequality but simply make it “fairer”. Most of those who advocate diversity policies do so because they abhor inequality. Yet, in the shift from “equality” to “diversity”, the most marginalized have often been forgotten. The focus shifted from addressing the needs of working-class people from minority communities to providing better opportunities for middle-class professionals. “The fact that some people of color are rich and powerful should not be regarded as a victory for all the people of color who aren’t”.

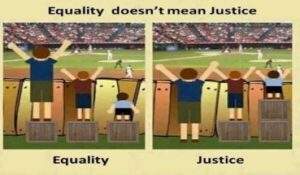

- Equity versus Equality

A related issue is the attitude toward equity and the consequences for affirmative action.

The cartoon below shows an interesting difference in the meaning of equity.

Source Unknown

For further reading

This difference describes, in general, the difference between Masculine and Feminine cultures and, consequently, between the Contest- and Network Mental image. In the Contest, the emphasis is on equal opportunity. In Network countries, on “fair” opportunity. Affirmative action is, in these cultures, a self-evident intervention to create equal chances.

Another paper in this series will look at the seven possible combinations of the four Hofstede values and the seven different rules of the game for policymaking. Making the content and priorities of DEI programs in, for instance, the USA, different from countries like The Netherlands, France, Nigeria and Japan. See: https://culture-impact.net/dei-and-mental-images-the-rules-of-the-game/

Literature:

Demertt Allison, Hoff Karla, Walsh James,( 2015)Behavioural development economics: A new approach to policy interventions. World Bank Group (2015), World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society, and Behaviour. Washington, DC: World

Heinich Nathalie (1988). · E-book Ce que n’est pas l’identité· 9782072801235 ,· september 2018 .· Adobe ePub

Henrich Joseph, Heine Steven H. The Weirdest People in the World (2010)How representative are experimental findings from American university students? What do we really know about human psychology? The University of British. Columbia Department of Psychology

Hofstede Geert: Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd Edition. 596 pages. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications, 2001, hardcover, ISBN 0-8039-7323-3; 2003, paperback, ISBN 0-8039-7324-1.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the. Mind. Berkeley: McGraw-Hill

Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R. R. (2004). Personality and Culture Revisited: Linking Traits and Dimensions of Culture. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science, 38(1), 52–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397103259443

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-827-

Malik Ken (2023) Focusing on diversity means we miss the big picture. It’s class that shapes our lives. The Observer January 29, 2023

Minkov, M. & Hofstede, G. (2014). Nations versus Religions: Which Has a Stronger Effect on Societal Values? Management Int Rev, 54, 801. doi:10.1007/s11575-014-0205-8

Pogosyan Marianna, Geert Hofstede: A Conversation About Culture. Beyond cultural dimensions. In Psychology Today, February 21, 2017

Søndergaard, M. (1994) Hofstede’s consequences: a study of reviews, citations and replications. Organization Studies, 15, 447-456

Waal Frans de, Primates and Philosophers. How morality evolved. Princeton University Press, 2006 ISBN13:9780691124476

Watters Ethan (2013) We Aren’t the World February 25, 2013, In Pacific Standard

Wursten Huib (2019). The 7 Mental Images of National Culture Leading and Managing in a globalized world ISBN-10: 1687633347 ISBN-13: 978-1687633347

0 Comments