The vulnerable human being

A cultural anthropological study on life and work of Vincent van Gogh

Drs. Carel Jacobs, social scientist; certified trainer intercultural communication. Email: careljacobs96@gmail.com

Abstract

This cultural anthropological study describes which characteristics have influenced life and works of the world most famous 19th century Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh in the countries where he lived, and vice versa his influence on the works of his foreign colleagues. An artist who only considered himself a true painter at the age of 27 and died at the age of 37, lonely and penniless.

Leading in this study will be the worldwide research of prof. Geert Hofstede into how national cultures differ in the basic values of life. Key in the article is the Dutch feminine culture, with sympathy for the unprivileged in society. This is explaining Van Gogh’s choice of themes, especially depictions of working people, often from a profound emotionalexperience of the simple and intimate life of peasant laborers, weavers and miners in the different countries where he lived and worked.

As a selftaught artist Vincent van Gogh was inspired for his artistic development by innovative ideas from colleagues. Especially in France where he learned new techniques and the use of vivid colors from his French colleagues, who had found each other in a new vision of reality: the individual experience of what the painter feels and experiences in his first impression: the impressionists.

Van Gogh had a complicated character and had a stressful life that often troubled him: unfinished studies, conflicting relations with family and friends, un unhappy love life and psychoses. After one of these psychoses he admitted himself for a year in a psychiatric institution, to relax. During this stay he detached himself from existing ideas about painting and developed his own style: the emotional reaction of the artist to his environment became his motive. Based on that he created his most famous paintings. As such we can consider him as the founding father of expressionism, with still many followers all over the world in the decades after.

Key words: Vincent van Gogh, cultural differences, Hofstede, The Hague School, individualism, impressionism, expressionism

Introduction

There will be few nineteenth-century painters we know more about than that of Vincent van Gogh. During his life he lived and worked in more than twenty locations in The Netherlands, England, Belgium and France. During the ten years he considered himself a fully-fledged artist, he produced about 850 paintings and approximately 1300 drawings, of which only a few were sold during his lifetime (Nix 2018). We also know what Vincent has looked like over the years. He painted dozens of self-portraits, more than 20 of them in the two-year period he lived in Paris. Not from vanity; often he could not afford models to paint. This however offered him the opportunity to experiment with perspective, colors and light.

We can also get to know Vincent Van Gogh through the many letters he wrote. According to art historians, there must have been more than a thousand, often multi-page, to his family, in particular to his benefactor brother Theo, who was four years younger. But also to other family members and colleagues. Many of his letters, often with sketches of the work in progress with detailed color descriptions, have been preserved, giving us a good insight into his soul stirrings, his passion, his creative mind, but also his doubts, his struggle with loneliness, his search for love, his psychoses and his self-destructive tendencies.

The linguistic content of his letters is exceptionally high. Historians believe that if he had not become a painter, he could have become a renowned writer. More than a third of his letters are in French. Not only because he spent a lot of time in France, which he regarded as his second homeland. But also because in the world of the well-to-do bourgeoisie from which he emerged at that time it was “bon ton” to correspond with each other in French. He often signed his letters to Theo with “tout à toi, Vincent” (ever yours, Vincent). Because the French could not pronounce “Van Gogh”, he signed his paintings with “Vincent” (Hulsker, 1980). In my study I will also talk about “Vincent” in a narrative. This means that I like to share with you Vincent’s intercultural experiences throughout his life as an artist.

Letter to Theo with the sketch of a digger, September 1881

Our journey through Vincent’s life will not be from an art-historical perspective and therefore not be a complete one. In a cultural anthropological study I will try to determine which characteristics of the country’s cultures where he stayed have influenced his life, and how that translated in to his works. And vise-versa, what was Vincent’s influence on the work of his foreign colleagues. As a travel guide I will introduce Prof. Geert Hofstede, who has conducted worldwide research into how people in more than 100 countries differ in dealing with the basic values of life. Although the countries where Vincent will reside have a completely different method of management, they all have the individualistic dimension in common: the interests of the individual come first (Hofstede 2010; see the country scores at the end of this article). In the nineteenth century this becomes clearly evident when a cultural movement develops in Western society that will become known as Impressionism, with influences on painting, literature and sculpture (Wursten 2021). Nevertheless, we must bear in mind that, although the countries in which Vincent lived all share the dimension individualism, this dimension has a different interpretation in each of these cultures. In the Netherlands, for example, there is a strong link with femininity (working in order to have a good life in private), in Belgium and France it is the opposition to the dominant top-down mentality of the elite, and in England seizing opportunities for success and prestige. This will become clear further on in this article.

Dutch culture

In my study I take the Dutch culture in which Vincent grows up as the starting point for our observations, after which we follow him in England, Belgium and France.

- In Hofstede’s research, Dutch culture has a low score on Power Distance (Hofstede 2010), that is, in general, a less dominant attitude of parents, teachers and bosses towards subordinates. Children are seen by parents as equals and are challenged to express their own opinions. Teachers and employers also accept this way of dealing with each other. How different is that in Belgium and France, for example, where contradiction by children, students or employees is absolutely not tolerated. How does Vincent experience this hard learning experience?

- The Dutch are generally regarded as individualistic (Hofstede 2010). Mind you, that’s not the same as being selfish! Privacy is of paramount importance: the right to be let alone. The company of close family and a few friends usually suffices, in an atmosphere with the untranslatable term “gezellig” (is far more than cozy). Example: The Netherlands has the highest camper- and touring caravan density in the world, with which families anytime can go wherever they want (Kooyman 2020). Loyalty to a very extended family up to and including great-nephews and -nieces in exchange for their protection, as in a lot of collectivist societies, does not play any role in Dutch society.

- The Netherlands also have a feminine culture (Hofstede 2010): working for having a good life, good relations with boss and colleagues and sufficient free time to be able to do nice things are the essence of life. Working part time by both the partners is accepted.

Sympathy for the underprivileged in society is also part of this Dutch way of life. We will see that the latter will mainly be the common thread in Vincent’s life. How will Vincent experience this in a competitive and prestige – masculine – oriented society like the UK?.

- Finally, the Dutch are less likely to panic when unexpected events occur, this means a low score on uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede 2010). They always look for a reliable solution. But it should also not be too casual. Social life must remain clear and structured. How does Vincent experience this in countries of residence such as Belgium and France, where uncertainty avoidance and the desire for control and – excessive – regulation play a major role in society? What does that mean for his emotional life and his work?

Dutch culture has some similarities with the Scandinavian cultures, but differs in all respects from all other cultures in the world. The above-mentioned characteristics (“dimensions” according to Hofstede) cannot be viewed separately from each other. They should always be studied in conjunction. Wursten describes the Dutch cluster of dimensions as a “network society”: “equality for all is the defining value. All stakeholders are treated equally, are autonomous and participate in decision-making. Decisions are made based on consensus i.e. a shared-interest”(Wursten 2019, p.33).

The Young Vincent (1853 – 1869)

Nienke Denekamp and colleagues from the Van Gogh Museum describe Vincent’s boyhood years in “De Grote Van Gogh Atlas”. A summary (Denekamp et al., 2015, p. 13-23): Vincent was born on March 30, 1853 in the village of Zundert, in the southern Dutch province of Brabant, where farm life on the poor arable land is very difficult. He is the son of a protestant clergyman, his mother is a well-born housewife. Vincent is named after his grandfather and after his older brother who died at birth exactly a year earlier. Vincent is followed by five more children, including his brother Theo, who is four years younger, with whom he will maintain close contact throughout his life.

The Van Gogh family belongs to the upper-middle-class. At home they have a maid, two cooks, a gardener and a governess. Every Sunday, the whole family walks through the village in their best clothes, humbly greeted by the rural residents. The clergyman is very popular amongst the poor farmers. Together with his wife, he often visits the sick and leaves money with the grocer for customers who cannot afford their groceries. This social character undoubtedly has influenced Vincent. In his wanderings through the area, he may already gain first impressions of the hard life of the agricultural residents, including many arable farmers and weavers. For many, it is hard to maintain a dignified existence.

Vincent is a quiet boy at school. At the age of 11, his parents take him out of school because they fear that he will be influenced too much by the behavior of the farmers’ sons in the area. From that moment on he is taught by his father and the governess. His mother teaches him to draw, crafts and sing, and instills a love for nature. At that time it is not yet clear that he has talent or motivation for this.

For his further development, Vincent is sent to a boarding school in Zevenbergen, where he will stay for two years. After that, at the age of 13, he attends the Hogere Burger School (high school) in Tilbury. Because of the enormous traveling time (three hours walk and then another twenty minutes by train) he is living with a host family. After two years, Vincent suddenly leaves school for unclear reasons and comes back to live at home. (end of summary).

Vincent as a young adult (1869 – 1879)

At the age of sixteen, his parents decide that it is in Vincent’s best interest to lead a working life, but at a socially acceptable level. He is hired as the youngest employee in the international art dealership Goupil & Cie in The Hague, which is co-owned by his uncle Vincent. His brother Theo is placed at the Brussels office. The two agree to remain loyal to each other from that moment on (Denekamp et al.).

London

After four years, Vincent is transferred to the London office. At that time, England is the first country in Europe to have an industrial revolution. In a period without wars, with abundant raw materials (from the many colonies), fuels (coal mines) and labor, all preconditions are present to undergo an explosive economic development. An open competition with plenty of possibilities to explore leads to many new initiatives. Inventions such as the steam engine (rationalization of the production process) and the steam train (transport) boost prosperity. London grows into a global city and becomes the financial heart of a leading nation with a lasting influence on surrounding countries. Vincent is introduced to the masculine English culture in which pursuing and showing success is an important occupation (Hofstede 2010). On Sundays he can often be found on Rotten Row in Hyde Park, where his eyes are on the many luxurious carriages, in which the rich like to show their successful existence to the people (Bailey, 2019). During his walks he makes sketches of the environment that he sends to his parents. These sketches have unfortunately been lost.

During his stay in London, Vincent also often visits The British Museum and The National Gallery. He admires the famous painters of farmers life Franҫois Millet and Jules Breton. But he is also very impressed by the 19th century British romantic painters John Constable who has a preference for working people on the land, and William Turner who is considered the greatest British landscape painter ever. In his most famous work, Turner sketches an unparalleled connection between the past and the present: during a flaming sunset, a steamboat brings an old warship to his last location to be scrapped. The extreme light conditions in this painting will inspire Vincent in his work later on.

William Turner: The Fighting Temeraire, 1839

William Turner: The Fighting Temeraire, 1839

Vincent is also confronted with the downside of the turbulent economy. The traditional English class society is rapidly transforming into a society with “haves and have nots”. He sees poverty in the streets and is impressed by writers such as Charles Dickens (A Christmas Carol) who denounce social injustice, abject poverty and the relationship between them. Deep in his heart he undoubtedly wonders whether his social motivation lies with the less fortunate. His decision to follow a calling as a lay priest may already be sown here. An unwanted reason to do so soon follows. He falls head over heels in love with his landlady’s 19-year-old daughter, whom he proposes to marry. She rejects him on the grounds that she is already secretly engaged to someone else. He has no choice but to leave his landlady’s house immediately. Because of this enormous love drama, he falls into a deep depression. He looks for comfort in the Bible. As a result, he increasingly does not show up for work and is fired.

His parents decide it might be better for him to leave England and get him a job at Goupil’s headquarters in Paris. Here too he immerses himself completely in the Bible and writes whole pieces about it for his brother Theo. Eventually, he is also fired there due to disinterest in the work.

Belgium

Through his Bible study, Vincent sees a future for himself as a missionary for the poor and oppressed. He tries a theology course, but can’t see this through. To continue his missionary urge, he applies as a lay preacher in the Borinage, a very poor mining region in Belgium, near the French border. By then he is 25 years old. He descends seven hundred meters (!) deep into the dangerous mine and sees how miners, their children and old workhorses are at work under gruesome conditions. This affects him enormously and he cares diligently for the well-being of these least fortunate. He gives away his own belongings, cares for the sick and the poor, and gives Bible readings to bring comfort. In the meantime, he draws miners and their families in his spare time to show this poor existence to the world.

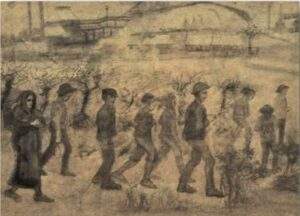

Miners in the snow to go at work, September 1880

Miners in the snow to go at work, September 1880

Vincent is here confronted with the typical characteristics of Belgian culture. On the one hand, it is characterized by a steep hierarchy from bosses to subordinates with a super bureaucratic structure as the organizational principle. On the other hand, a very high score for individualism (Hofstede 2010). Deep in their hearts, the Belgians try to avoid the consequences of the hierarchy: ‘drawing your own plan’ (Wursten, 2019, p. 50), often explained by historians as a protest against the many foreign occupations that have gripped the country for hundreds of years. This is no different in the Borinage. On the one hand, the miners and their families passively suffer the fate of unscrupulous exploitation by the mine owners, even after serious accidents. On the other hand, they each try to keep their existence bearable in some way. Vincent’s involvement, however well-intentioned, is regarded by the authorities as harming their governance in the region (Tate, Seven things). After six months his contract will not be renewed. “Mr.Van Gogh does not have the gift of the word” is the motivation of the Committee (Denekamp et al.).

Yet Vincent can’t let their poor existence go. He will and must record this and draw attention to it. He stays in the region for a while and records almost day and night his hundreds of observations on paper, which he mainly donates to his landlady as a contribution to the costs of lodging. Not knowing that his landlady will light the stove with it the next day.

Women carrying sacks of coal in the snow, November 1882

Women carrying sacks of coal in the snow, November 1882

All things considered, the seed was sown here for his birth as an observant artist: outspoken recordings of emotional events from daily life, unconsciously at that time as one of the forerunners of what will later become known as Impressionism. However, he no longer has a source of income. How long does he want to live on the money of his family, his brother Theo tells him. This leads to a break between the two brothers of more than a year.

The breakthrough! Vincent feels like an artist (1880 – 1886)

After a year, the relationship between Vincent and Theo recovers. Vincent writes to him that he has decided to become a painter. In an emotional letter to Theo, he describes what he himself considers as his “liberation”:

“A bird in a cage in the spring knows very well that there is something it could do for. He feels very well that there is something to do, but he cannot do it. What is it? He doesn’t remember well. Then he has vague ideas and says, “The others make their nests and bring forth and raise young ones,” and then he hits his head against the bars of the cage. But the cage remains and the bird is mad with pain. “Look what a idler,” says another bird flying by. “That one there is a kind of rentier”. Yet the prisoner remains alive, he does not die, nothing can be seen from the outside of what is going on inside him, he is doing well, he is rather cheerful in the rays of the sun. But then comes the time of the trek. Bouts of depression. “But,” say the children who take care of him in the cage, “doesn’t he have everything he needs?” But he sits out looking at the sky where a thunderstorm is threatening and he feels the rebellion against his fate within. “I am in a cage, I am in a cage, so I am not missing anything, you fools! I have everything I need! Oh, freedom, please, let me be a bird like any other! “( Letter to Theo, in French language, July 1880. Hulsker 1980).

He is now 27 years old and realizes that he has no time to lose to be able to make a career as a selftaught artist. His favorite hero is Jean Francois Millet, a French painter who is famous throughout Europe for his scenes about the harsh life of peasants. Vincent asks Theo to send as many prints as possible so that he can practice with anatomy and perspective. To his delight, he progresses quickly: “I have been making scribbles for quite a long time without making much progress, but lately, it seems to me, things are getting better, and I have high hopes that it will go even better” (Denekamp et al., p. 68). To make salable work, he has to develop even further. Theo offers to regularly send him money until then, in exchange for selling works afterwards.

Vincent returns to live with his parents, who have since moved to Etten. He sets up a small studio next to the presbytery. During that period he is also apprenticed to his cousin by marriage Anton Mauve in The Hague, at that time a highly respected Dutch painter in mostly somber colors, in an art movement known as The Hague School.

Anton Mauve Women from Laren with Lamb 1885

Anton Mauve Women from Laren with Lamb 1885

Because of Anton’s prominent position in the artist world, Vincent also gains access to other highly esteemed painters such as Willem Maris and Hendrik Willem Mesdag, whose techniques he studies closely. Anton gives Vincent instructions for making drawings and paintings. He encourages Vincent to experiment with oil paint as well and provides him with all the necessities. In a letter to Theo, Vincent writes: “Because Theo, with that painting starts my actual career, you don’t think it’s good to just look at it like that?” (Denekamp et al., p.77). However, Mauve ends the collaboration abruptly when he learns that Vincent is taking in a pregnant prostitute and her five-year-old daughter. She frequently poses for him. Although this brings him into contact with the physical and moral poverty of the poor and underprivileged in the city, this coexistence does not last longer than a year (Thomson 2007).

Vincent visits workers at home in order to be able to work from a model, often in work clothes. He is looking for a way to show his aptitude, as it were. To this end he intensely studies the peasant life and experiments, inspired by Rembrandt and Turner, with light and dark. For his studies he is welcome with a simple farming family in the immediate vicinity. In April 1885 he paints The Potato Eaters, his first large-scale figure work piece. He is very proud of that !

The Potato Eaters, April-May 1885

The Potato Eaters, April-May 1885

A few months later, the single daughter of the house turns out to be pregnant. Vincent has nothing to do with that, but the local catholic priest forbids his parishioners to pose for him any longer. Disillusioned, Vincent leaves this region and also his homeland, never to return. He travels to Antwerp to study painting at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. He does not last long there and travels on to his brother Theo in Paris.

From dark to light: Paris (1886 – 1888)

France, with successively a Sun King, an Emperor and a few post-revolutionary regimes, turned over the centuries into a centralist nation-state, which developed very rapidly in the 19th century. All power is concentrated in Paris. The departments into which the country is divided have very little autonomy from the central government, comparable to a solar system in which numerous satellites are constantly orbiting the core (Wursten 2019).

In this ‘zeitgeist’, Paris profiles itself as the undisputed world capital of art. The yearly Salon is the annual pinnacle of bourgeois cultural life, where the top paintings are exhibited and traded. Academic painting depicting intimate landscapes is regarded by the general public as clear proof of artistic quality.

During this period, however, a kind of “counter-movement” also develops, leading to an entirely new conception of art. A group of young artists including Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas tries to break free from the prevailing cultural elite and find each other in a new vision of reality: the individual experience of what the painter feels and experiences in his first impression. The group experiments extensively with light and color effects, with a fine, dotted or striped design and with a light brush stroke that blurs the contours, as if it were a snapshot. Great boosts are the development of new, colorful pigments and the invention of the paint tube, which allows artists to paint outdoors, en plein air, which they also do en masse. “Impressionism” is born.

In the middle of this Impressionist movement, in 1886, Vincent arrives in Paris, now 33 years old. Together with Theo, he moves into a house in the Montmartre district, the art center par excellence, with many entertainment venues, the natural environment of the bohemian. With the gray palette of The Hague School in his cultural baggage, he is confronted with the expression of his French colleagues. At first he appreciates this only moderately: “sloppily painted”, “badly drawn”, “poorly colored“(Denekamp et al.). But Vincent is also eager to learn. He tries to master the new painting techniques, with many stripes and dots. Because he cannot afford models, he makes a series of self-portraits in front of a mirror. He experiments with a variety of postures and uses brighter colors in his works. To give an example we observe his self-portrait after he just has arrived in Paris and just before he left Paris:

self-portrait, Paris 1886

self-portrait, Paris 1886  self-portrait, Paris 1888

self-portrait, Paris 1888

It is becoming increasingly clear that life in the modern, dynamic metropolis with an ever faster developing industrialization is not for Vincent. In addition, his health is failing him. He wants to get out of this busy, messy city, the unhealthy nightlife and the complicated artist’s world. He is friends with the painters Paul Gaugain and Émile Bernard and proposes to them to set up an artist colony in the south of the country in which artists inspire each other and exchange works with each other.

The highlight: Arles (1888-1889)

In general, the natural borders of a country also determine the ethnografic borders. However, there are also many subcultures within countries. This is also the case in France, where the sober, strict social culture in the north contrasts sharply with the more optimistic way of life in the south, described by Hofstede as ‘indulgence’: a tendency to allow relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun’ (Hofstede 2010, p. 281). In what the French themselves consider as “joie de vivre “. Indulgence has a negative correlation with the dimension Power Distance (hierarchy), which ties in very well with the low score for this dimension in Dutch culture: considering each other as equal (Hofstede 2010).

It is in this culture where Vincent ends up when he takes the train to the south and finally arrives in Arles, a village in Provence about a thousand kilometers from Paris. Vincent quickly feels at home here and makes many friends, with whom he drinks many glasses of absinthe on the terrace of the cafe on the Place du Forum.

Vincent’s greedily absorption of the colorful farmland and the vibrant provincial life inspires him to an almost insane productivity. In the 15 months he stays here, he produces about 200 paintings and more than 100 drawings and paintings using watercolors (Hetebrügge 2009).

Vincent’s way of painting is becoming increasingly impulsive and intuitive. The colors are becoming more and more exuberant, with the use of many variations in the complementary colors yellow and blue, the colors of the Provencal summer.

Bridge at Arles with washing women (Pont de Langlois), 1888

Bridge at Arles with washing women (Pont de Langlois), 1888

Vincent is also welcome with the postal worker Joseph Roulin (with an extreme beard) who allows him to paint many portraits of him and his family members.

Joseph Roulin, Arles 1889

Joseph Roulin, Arles 1889  son Camille Roulin, Arles 1888

son Camille Roulin, Arles 1888

This period can rightly be called the peak of his career. He still dreams of a “Studio of the South” where artists feel at home and inspire each other, where he can live with his friends Émile Bernard and Paul Gaugain and possibly with Theo. And indeed Gaugain comes to Arles. Vincent prepares for his guest with a fully furnished bedroom, but also with many paintings that Gaugain will certainly like, including vases with sunflowers.

Vincent is not doing well (1888 – 1890)

Gaugain’s arrival in Arles will dramatically change Vincent’s life. Initially they get along well and also paint a lot together in the same places. But their artistic interpretations increasingly degenerate into fierce discussions and even arguments. Their characters turn out to be incompatible. Finally, on December 23, 1888, one of the arguments ran high. Nobody knows exactly what happened between the two at that moment. The fact is that Gaugain flees the house never to return and that Vincent is left with a largely cut off ear. He is badly injured, ends up in hospital and has a serious nervous breakdown (Denekamp et al.). Two more nervous breakdowns follow after discharge from the hospital. Vincent becomes a nuisance in the neighborhood and he is re-admitted to hospital by order of the mayor. He is delusional and even ends up in solitary confinement. His idealized world of an artist colony is over.

After consultation with Theo, Vincent has himself admitted to a psychiatric institution not far from Arles, to relax. He stays in this institution for a year. He is given the opportunity to paint and he paints the lilacs and irises in the garden, but also the distant mountains. From his room he paints the almond blossom just behind the wall of the garden. During his stay in the institution he produces 150 paintings and as many drawings.

Vincent also increasingly detaches himself from existing ideas about painting and creates a free role for himself. He develops his own style, uses larger lines and his works become more abstract. Not the representation of reality but the emotional reaction of the artist to his environment becomes his motive. The Starry Night is the best example of this. It is an imaginary night scene with yellow stars above a small village with a church tower with on the left a flaming cypress and on the right alive trees against the hills. Creating this freedom of role Vincent in a way becomes one of the forerunners of “expressionism”, which will have many more followers afterwards in the decades to become.

The Starry Night, Saint Rémy June 1889

The Starry Night, Saint Rémy June 1889

Vincent “returns home” (1890)

Vincent has lost the figment of the imagination in the south. He longs to go back north. Theo proposes him to move to Auvers-sur-Oise, a small artists’ village not far from Paris. There lives a homeopathic doctor who is also an art lover who wants to guide Vincent in his recovery. In 1890 Vincent moves into a simple inn. He likes the environment very well. It reminds him of the countryside in Brabant, Arles and Saint-Rémy, where farmers from the area grew potatoes, corn and beans. In a letter to Theo dated 11 May 1890: “It is extraordinarily beautiful, it is the real countryside, characteristic and picturesque” (Hulsker 1980, p. 559). Vincent feels he has returned home again. He loves painting the area around Auvers.

Vincent notices that he is an ever increasing financial burden for Theo, who is not doing well in terms of health and finance. His obsession with art has yielded nothing to him. He thinks he has failed in life. On July 27 1890 he paints what will turn out to be his last work: the jagged shapes of the tree roots in a logging forest. He does not finish the painting and returns to the inn. Several hours later he enters the cornfields of Auvers for the last time and tries to end his life with a pistol. However, he hits his chest but misses his heart. Badly injured, he stumbles into the inn. Theo rushes to Auvers, but cannot prevent Vincent from dying in his arms on July 29, 1890, only 37 years old. Just six months later, Theo also dies, succumbed to the effects of syphilis. Both brothers are buried next to each other in the cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise.

Tree roots, Auvers-sur-Oise, unfinished, July 27 1890

Tree roots, Auvers-sur-Oise, unfinished, July 27 1890

Postscript: what has Vincent brought us?

The relationship between culture and art

In the introduction to this article, I committed a cultural anthropological research in which I would try to find out which cultural dimensions in countries where Vincent stayed have influenced his life, and what we see in his works.

As a starting point for our anthropological research, we looked at the Dutch network society, in which equality for everyone is the core value and in which all stakeholders can have a say in everything. We have emphatically experienced that this is absolutely not the case in both Belgium and France, where the dominant elite rules. These experiences deeply moved Vincent both emotionally and artistically. His experiences in the Borinage in particular have fueled the realization in him that he could mean more to society as a creative missionary than an apostolic missionary. In France we saw that it took him a lot of effort at first to break away from the familiar, safe view of society as he had learned it in the best traditions of The Hague School, towards a more challenging, more impulsive view of everyday life. But afterwards also went for it!

I indicated that all countries where Vincent has lived have a western, individualistic culture in which the interests of the individual take precedence over the interests of the group. We have found that these characteristics, especially in the second half of the nineteenth century, have also had a lasting influence on painting in England, Belgium and France, in what I have termed the rise of ‘Impressionism’.

Mental Health

In many biographies about Vincent, his difficult character and fragile state of mind are discussed: emotional, impulsive and easily hurt, with an unbridled zest for work that was alternated with delusions, nervous breakdowns and depression. Many psychologists and psychiatrists have considered the background of this. Is the fact that he is named after his brother who died on the exact same day the year before being the reason he had to live up to what his brother could never achieve for himself? Is it the stress of constant money problems, hardly sold anything paintings and remained financially dependent on his younger brother? Or were there deeper problems that ultimately resulted in his suicide in 1890? In 2020, a group of psychiatrists attempted to analyse this on the basis of his letters. This shows that it must have been a combination of negatively influencing factors: a bipolar disorder combined with a borderline personality disorder, a heavy alcohol addiction (absinthe at that time had 72% alcohol) and brain damage due to his physically and mentally exhausting lifestyle (Nolen et al.). Despite these disorders, he had a tremendous willpower and great perseverance. In several letters he wrote that painting had therapeutic significance for him. This belief has led him to be particularly productive in his active periods. What we can still enjoy today.

The vulnerable human beings as an object of study

It is important to notice that Vincent, as an exponent of the Dutch feminine culture in which care for the least fortunate is of paramount importance to everyone, has steadfastly adhered to his intention to report on this from the very first moment. In all his studies, the hard life of agricultural workers was his great source of inspiration. His life in the Borinage only fueled that. Also in his later works he never denied the recording of the life of the humble man, which we can see in his many sketches and paintings on this theme. He has never been tempted to paint technological highlights or industrial objects.

Inspirator for many artists after him

Vincent has also been a major influencer of innovations in painting, for which he only received recognition after his death. Once he has chosen a life as a painter, he shows an enormous eagerness to learn to master as many painting techniques as possible, with pencil, chalk, water color and oil paint as well as composition, and he experiments with this particularly in numerous self-portraits. After his Parisian period, as a post-impressionist, he increasingly detached himself from existing ideas about painting and created a free role for himself: the artist’s emotional reaction to his environment becomes his ultimate motivation. His fellow artist Pissarro predicted that Vincent would “… be either go mad or leave the impressionists far behind’ (Bailey, 2021).

Vincent is one of the forerunners of expressionism at the beginning of the twentieth century. In it, the perspective is largely abandoned, with high-profile painters such as Edvard Munch (“The Scream”), Egon Schiele and Paula Modersohn. Also in 20th and 21th century artists are still inspired by Vincent.

Vincent has also had a great influence on many of his colleagues in terms of color use. His exuberant use of bright colors, particularly in his Provencal period, has inspired, among others, many British artists like Harold Gilman who applied Van Gogh’s use of bold colors and expressive brushwork to English motivs, the French Fauvists, a group of painters using unmixed primary colors (Matisse is the main representative of this group) and the German expressionists. Painters all over the world have followed this in many decades after.

After all Vincent posthumously has achieved what his intention was for life:

being meaningful to society

What are we left with here? An extensive oeuvre that is still highly appreciated all over the world. For the less fortunate among us who cannot afford a Van Gogh at home, there is still plenty to admire. I recommend you to visit:

– Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (NET), with 200 paintings and 500 drawings

– Kröller-Müller museum in Otterlo (NET), with 90 paintings and 180 drawings

– almost every renowned museum in the world with at least one of Vincent’s works

Country scores on a scale 1-100 based on the research of prof. Geert Hofstede

| NET | UK | BEL | FRA | ||

| Power Distance Low | 38 | 35 | 65 | 68 | Power Distance High |

| Collectivistivism (IDV-) | 80 | 89 | 75 | 71 | Individualism (IDV+) |

| Femininity (MAS -) | 14 | 66 | 54 | 43 | Masculinity (MAS +) |

| Uncertainty Avoidance low | 53 | 35 | 94 | 86 | Uncertainty Avoidance high |

| Short Term Orientation | 67 | 51 | 82 | 63 | Long Term Orientation |

| Restraint (IVR -) | 68 | 69 | 57 | 48 | Indulgence (IVR +) |

About the author

Carel Jacobs is a Dutch social scientist. He is a certified trainer in intercultural communication based on the worldwide research of professor Geert Hofstede on cultural differences. Specialization of Carel Jacobs is the health care sector: lectures and training activities for doctors, case managers dementia and nurses about how to be effective in communication with patients and their families from non-western cultures.

This article is written on personal interest.

References

Bailey, M.: How Van Gogh fell in love with London. Tate Gallery, February 4, 2019

Bailey, M: Pissarro predicted that Van Gogh ’would either go mad or leave the impressionists far behind’. Blog: theartsonnewspapar.com/blog/Pissarro-on-van-gogh. February 19, 2021

Butterfield: The troubled life of Vincent van Gogh and the birth of expressionism. (2011). Bonniebutterfield.com

Denekamp, N.,Van Blerk, R, Meedendorp, T.: De Grote Van Gogh Atlas. (2015). Van Gogh Museum, Rubenstein, Amsterdam.

Hetebrügge, J,: Vincent van Gogh 1853-1890. (2009) Parragon, New York

Hofstede, G, Hofstede, G-J, Minkov, M. (2010): Cultures and organizations; software of the mind. McGraw-Hill, New York

Hulsker,J, : ‘Dagboek’ van Van Gogh (1970). Meulenhoff, Amsterdam

Hulsker, J. : Vincent van Gogh; een leven in brieven. (1980). Meulenhoff, Amsterdam

Jansen, L. : Vincent van Gogh en zijn brieven (2019). Van Gogh Museum

Kletter, S: Weergave van het moment, het licht, de weersgesteldheid en de atmosfeer. www.artsalonholland.nl/kunst-stijlen/impressionisme

Kooyman, M.: “Liever op eigen wielen’’. In AD, November 18, 2020, p. 20-21

Leeman, F., Sillevis, J.: De Haagse School en de jonge Van Gogh. (2005). Waanders, Zwolle

Manoukian, M. : The tragic real-life story of Vincent van Gogh. Grunge, July 2020

Nix, Elizabeth: 7 things you may not know about Vincent van Gogh. In: History, August 22, 2018

www.history.com/news

Nolen, W, Meekeren, E.van, Voskuil, P, Tilburg, W.van: New visions on the mental problems of Vincent van Gogh; results from a bottum-up approach using (semi-)structured diagnostic interviews. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 30-08-2020, page 1-9

Rovers, D.: Van Gogh wilde Jezus zijn. In: Trouw, July 27 2015, page 6-7

Seven things to know about Vincent van Gogh’s time in Britain. No author mentioned. www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/vincent-van-gogh

Thomson, B: Van Gogh schilder; de meesterwerken (2007). Van Gogh Museum. Waanders, Zwolle

Walther, I.F., Metzger, R, (2006): Van Gogh, alle schilderijen. Taschen, Köln

Wikipedia: Vincent van Gogh. Wikipedia, 11-12-2020

Wursten, H. : The 7 Mental Images of National Culture; leading and managing in a globalized world. (2019) Hofstede Insights. Amazon.com

Wursten, H: Reflections on Culture, Art and Artists in Contemporary Society. In JIME, July 2021

List of illustrations

Letter with sketch of a digger September 1881

Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo, September 1881

Pen in inkt on paper, 20.7 x 26.3 cm.

Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam, The Netherlands

William Turner: The Fighting Temeraire, 1839

Oil on canvas, 90,7 x 121.6 cm

National Gallery, Londen, United Kindom

Miners in the snow going at work September 1880

Pencil, colored chalk, and transparant watercolor on wove paper,

44,5 x 56 cm

Kröller Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands

Women carrying sacks of coal in the snow, November 1882

Chalk, brush in ink, and opaque and transparant watercolor on wove paper

32,1 x 50,1 cm

Kröller Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands

Anton Mauve: Woman from Laren with lamb, 1885

Oil on canvas, 50 x 75 cm

Kunstmuseum, The Hague, The Netherlands

The Potato Eaters, April-May 1885

Oil on canvas, 82 x 114 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Self-portrait, Paris, September-November 1886

Oil on canvas, 46,5 cm x 38,5 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Self-portrait, Paris, December 1887-February 1888

Oil on canvas, 61,1 cm x 50 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Bridge in Arles (Pont de Langlois), March 1888

Oil on canvas, 54 x 64 cm

Kröller Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands

Joseph Roulin, sitting at a table, Arles, August 1888

Oil on canvas, 81,2 cm x 65,3

Museum of Fine arts, Boston, USA

Camille Roulin, Arles, November-December 1888

Oil on canvas, 40,5 cm x 32,5 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

The Starry Night, Saint Rémy, June 1889

Oil on canvas, 73,7 cm x 92,1 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Tree roots, Auvers-sur-Oise, July 27 1890

Oil on canvas, unfinished, 50,3 cm x 100,1 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

0 Comments