The Interplay of Culture in Migration Patterns: A Swedish Perspective

By Philip Sjögren

Abstract

The global refugee crisis that commenced in 2015 witnessed an influx of Syrian refugees into European territories. While Germany received a noteworthy commendation for accepting approximately 1 million refugees, constituting 1.25% of its population, Sweden too exhibited a remarkable stance. Sweden accepted 160,000 refugees, which corresponds to 1.6% of its population. The precedent of such generosity can be traced back to earlier global conflicts such as the Yugoslav War in the early 1990s when Sweden harboured 100,000 refugees. A prominent example was also in 2007 when the city of Södertälje welcomed more Iraqi refugees than the entirety of the United States did in the same year.

Sweden’s population in 2022, standing at 10.5 million, consists of over 2 million foreign-born residents. That puts Sweden at the highest levels in Europe for the share of the foreign-born population. This is the direct result of Sweden’s longstanding policy of promoting immigration.

This demographic transformation is predominantly credited to immigration from neighboring countries, especially Finland, which was the major source of immigrants until 2016. Post-2016, Syrian immigrants have outnumbered all other demographics.

However, in a striking “paradigm shift” the current right-wing Swedish government, which assumed power in 2022, has aimed to limit Sweden’s acceptance of asylum seekers to the lowest level in the EU and to reduce the quota for refugees from the previous 5,000 per year to 900. This change in policy is not exclusive to the right-wing government, as the preceding Social Democratic government also introduced more restrictive measures in late 2015.

Introduction:

This paper looks at what elements of Sweden’s migration policy can be explained culturally. It postulates that the liberal policies before 2015 can be explained by low masculinity, low uncertainty avoidance, and high indulgence, referring to Hofstede’s 6D model. However, the current shift might be primarily reactionary, influenced by the significant societal impact of mass immigration more than any cultural dimensions.

The ensuing sections will delineate the history of migration in Sweden and then analyse the contemporary policy transformation. The hypothesis presented posits that the current policy is a consequence of the increasing polarity between viable government alternatives leaning either right (against immigration) or left (pro-immigration). Thus, the radical policy shift may be more the result of a global trend of governmental polarization than a deeply entrenched cultural phenomenon.

Section I: Swedish Migration History: Transition from Emigration to Immigration

Section II: Escalating opposition to immigration

Section III: Impact of Culture on Swedish Migration Policy: An Analysis Based on Hofstede’s 6D Model

Section IV: Conclusion: The Interplay of Culture and Political Influence on Swedish Immigration Policy

Section I

Swedish Migration History: Transition from Emigration to Immigration

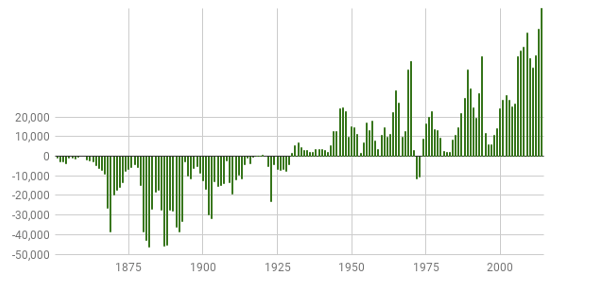

Net migration to Sweden by year in absolute numbers

1850-1929 – The Era of Net Emigration

Between 1850 and 1929 approximately 1.2 million Swedes, nearly 20% of the population, emigrated. Most left for North America. The primary drivers for this mass exodus were partly religious aspirations and for some probably the spirit of adventure. But for the majority, it was poverty. Industrialization was late in Sweden and the economy was still heavily reliant on agriculture. A series of bad crops and famines in the 1850:s and 1860:s pushed many to leave the country. These emigrants’ letters back home from North America probably created a pull-factor. Swedish folklore tells us how the emigrants became farmers, mainly in Minnesota as many town names indicate: Borgholm, Karlstad, Lindstrom, Malung, Mora, Scandia, Ronneby, Upsala, Viking and Stockholm to name but a few. But in fact most emigrants actually moved to the large cities, of which Chicago was the main one. In 1900, “The Windy City” of Illinois accommodated up to 100,000 Swedish-born inhabitants, comparable to Gothenburg at the time, the second-largest city in Sweden. Emigration continued to dominate through the 1920s with an interruption during World War I.

1930-1942 – A Period of Uncomfortable Shift

While Sweden managed to remain neutral during World War I, its industry sustained an export-led expansion in the 1920s that had begun in the late 1800s. In the 1930s, a combination of economic and social progress in Sweden and increasingly difficult migration conditions led to a small but notable net migration into Sweden for the first time in modern history. The immigrants were primarily Europeans.

Sweden’s shift in migration patterns became apparent when Nazi policies led to an increase of Jewish migrants asking for, but being denied, the right to stay. However, when Swedish authorities attempted to send them back to Germany, these German citizens were denied entry. This led Sweden and Switzerland to threaten Germany to halt visa-free travel between the countries. The German response was to introduce the infamous ‘J’ marking on Jewish citizens’ passports, which tragically was (ab)used by multiple countries, including Sweden.

Amid these tense times, the divides within Sweden deepened. When the authorities contemplated allowing 10 (!) Jewish doctors entered the country in 1939, and a meeting was held among the students of Uppsala. Approximately 60% of the nearly 1,000 participating students voted against their entry, citing reasons ranging from labor market arguments to pure racism. Still, a few Jewish Children were allowed entry, but without their parents. In total, some 500 children were saved this way, whereas their parents mostly died in the camps.

The Russian attack on Finland in November 1939 marked a turning point in Sweden’s migration history. The country declared itself non-neutral but not co-belligerent, i.e. it was explicitly on the Finnish side but would not engage in fighting. In practical terms, this meant sending arms and allowing Swedes to join the Finnish military but not sending any troops. It also resulted in 70,000 Finnish children being hosted in Swedish families during the war, many of whom eventually chose to stay.

The occupations in 1940 of Denmark and Norway further complicated the situation. In the beginning, it was unclear who was allowed to stay in Sweden or not. While non-Jewish Norwegians were allowed entry to Sweden, Norwegian Jews crossing the border depended on the goodwill of the local migration officer and sometimes even of that of the individual decisions of the border guards they happened to meet. At the same time, German troops and hardware were allowed to transition to and from Norway on Swedish railroads. The coalition government was deeply split on the topic of transiting German troops, with the Social Democratic Prime Minister eventually siding with the right-wing members of his government tilting the majority that way.

1943 – The shift in attitude

The major mental shift about migration can probably be dated quite exactly: November 1942. That was when the Germans started deporting Norwegian Jews to concentration camps. The deportations were well reported in Swedish media and the public opinion reacted strongly. Consequently, the authorities changed tack and suddenly all refugees from Norway and Demark were allowed in. In early October 1943, when the Nazis attempted to deport the roughly 8,000 Jews of Denmark, almost all of them (and their non-Jewish families) were shipped to Sweden in small boats over a span of ten nights.

This shift continued with the operations of the “white busses.” These were initiated by a Latvian refugee, Gilel Storch, who, after numerous attempts, managed to secure an agreement with Himmler thanks to the unlikely help of Felix Kersten, Himmler’s part-Swedish masseur (!). This led to red-cross-marked white buses going to several Concentration Camps to transport inmates to Sweden. The figurehead of that effort was Prince Bernadotte, later the first negotiator between Palestinians and Israelis (and killed in Palestine in 1948). The white busses were first meant to take Scandinavian inmates only but eventually took some 19,000 of which many were non-Scandinavians (see note[1].)

The end of the war also meant a large influx of refugees from Eastern Europe. Among the 30,000 civilians who often came in tiny boats across the Baltic were German and Baltic soldiers who had fought with the Germans against the Soviet Union. In June 1945, the Soviet Union requested they be returned. Eventually, Sweden sent some 3,000 Baltic and German soldiers to the Soviet Union. Again, media coverage created a strong opinion in favor of the refugees. Most civilians were allowed to stay.

Post-World War II

Sweden’s economy was largely unscathed by the war. Swedish products such as steel, telephones, timber, paper, roller bearings, and trucks were again being exported around the globe. But labor was in shortage. Workers from neighboring countries, especially Finland, were welcomed throughout the 1950:s. A free labor market between Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland) was created in 1954. But companies also sent recruiters further away to attract labor, with workers coming from Italy and Yugoslavia.

The foreign-born population increased from 100,000 in 1945 to 538,000 in 1970.

1970-2016: Transition from Labour Migration to Political Refugees

In the wake of the oil crisis in the 1970s, labor migration ground to a halt. But a new source of migration was increasing – political refugees. Throughout the 1970s, these political refugees originated from Chile, Greece, Turkey, and Argentina.

Global politics were increasingly visible among Swedish immigrants. In the 1980s they arrived from Poland (due to the communist regime’s attempts to crush Solidarity) and Iran ( i.a., due to the Iran-Iraq war which led young men to flee Iran to avoid being drafted). By the 1990s, Yugoslavia, and mainly Bosnia, had become a major hot spot, with a large number of refugees. Then came Iraq in the 2000s and Syria from 2011 onwards, reaching a peak in 2015-2016.

These consecutive waves of migrants are reflected in Sweden’s current population; as of 2022, foreign-born individuals constitute 20%.

Section II – Escalating Opposition to Immigration

In the 1930:s, opposing voices were raised about immigration. However, from 1945 to 1990, they remained relatively subdued. Some argue that anti-immigration sentiment was suppressed, though the author contends that it was more likely a confluence of circumstances that led to the apparent silence. First, the anti-immigration faction was substantially ‘on the losing side’ in WWII, so there was most probably a sentiment to distance oneself from that side’s policies. Second, the post-war labor shortage and robust economic development mitigated potential conflicts.

However, beginning in the early 1970s, societal tension started brewing. The multiple crises of the period, rising unemployment, and a growing foreign-born population gradually amplified resistance to immigration. By the early 1990s, this opposition had grown loud enough to enable a communal party, the Sjöbo Party, to rise to power in the commune on an explicitly anti-immigrant platform. They peaked at 33% of the local votes in 1994. Although the party was local, media coverage was national and negative voices on immigration grew louder and louder.

In 1991, a national party, New Democracy, was founded and made it all the way to the national parliament (the Riksdag) the same year with almost 7% of the national vote. They were jovial, playful and attracted a lot of people who did not fit the “traditional” mood. They soon imploded due to individual disagreements among their parliamentarians and leaders. With their eviction from Parliament in 1994, there was again a fairly broad political consensus about politics. But a seed of disagreement had been planted in the debate. Those opposing immigration still found it hard to be listened to, but the debate grew.

This resistance became even more pronounced in the early 2000:s when the Sweden Democrats (SD) started rebranding themselves to become electable. As described in the white paper commissioned by the party itself in 2018, the party was founded by a group of neo-nazis in 1988. When the current party leader, Jimmie Åkesson, took the reins in 2005, he also started a cleansing process of its most overtly extreme members that is ongoing to this day. The 2022 election saw SD become the second-largest party after the Social Democrats, with rhetoric comparable to many extreme right-wing parties across Europe and beyond.

The 2022 parliamentary election resulted in a political landscape demanding collaboration between starkly contrasting parties to achieve a majority. (note[2].)

Following lengthy negotiations, the Moderaterna (traditional right), Kristdemokraterna (Christian Democrates, right), Liberalerna (liberal, center right) and the SD (extreme right) signed an agreement. This allowed the creation of a right-wing government without the Sweden Democrats but with their support in Parliament in exchange for a promise to implement a lot of their policies, with migration being a significant point of contention.

Regarding migration, the agreement stipulates:

- Legislation on asylum to be restricted to be no more generous that the minimum obligations defined in EU legislation,

- Fight against the “shadow society” – in short, people with no right to stay in the country are to leave the country,

- Increase the number of individuals returning to their country of origin and of actions supporting such returns,

- Increased requirements on migrants with low qualifications and improved conditions for highly qualified individuals,

- Increased efforts to revoke attributed residence permits,

- Tightening of the conditions for family reunification immigration,

- Increasing demands on immigrants to integrate into Swedish society (e.g.- as a pre-condition to obtaining the nationality).

Early in 2023, the government is trying to accelerate work along the agreed objectives. For example, on May 29, 2023, it announced the introduction of tests for individuals seeking to obtain the Swedish nationality. The test will consist of two parts: Understanding of the Swedish Language and knowledge of Swedish society.

Section III – Impact of Culture on Swedish Migration Policy: An Analysis Based on Hofstede’s 6D Model

Which of the policies described above, if any, can be explained by cultural characteristics?

Hofstede’s 6D model of cultural dimensions describes Sweden as an extremely feminine, very uncertainty-tolerant, and very indulgent society. This characterization implies a societal tendency to prioritize the welfare of others, to seek consensus, to support the disadvantaged and the underdogs, to embrace changes without exhaustive planning, to exhibit limited apprehension towards foreign influences, and to maintain a general optimism regarding the present and the future alike. It is interesting to note that Sweden is quite extreme in several of Hofstede’s dimensions, which is confirmed in the World Value Survey. The Nordic countries are quite similar, but Sweden is, on most dimensions, more to the edges than Norway, Denmark and Finland.

How does this translate into the politics of migration?

In the early post-war years, migration was mainly waves of refugees. At first glance, Sweden letting some 50,000+ refugees enter the country can be said to be in line with caring for the disadvantaged. But large flows of refugees were moving across Europe into other countries with very different cultural characteristics and allowed to stay there. So, without much more analysis, the author would claim that this stage is certainly not cultural but more a coincidence.

In the following period, between 1950 and 1970, the driving force was predominantly practical: to increase the supply of labor. Of course, culture certainly impacted how it was done: there was probably less planning and less paperwork than other more uncertainty-avoiding countries would have opted for in the same situation. But the policies were largely a result of global forces rather than of local culture.

However, from the 1970s onwards, with politically motivated immigration, the narrative largely shifted towards extending assistance to those in need, somewhat coupled with arguments that a small, export-dependent nation like Sweden would derive benefit from an expanding and diversified population.

To the author, only the period 1970-2016 seems to have a clear cultural dimension. Helping refugees from various civil and international wars, having very little planning for how to receive or integrate the refugees and arguing to one’s own population to extend compassion for the suffering. Two more examples of this were:

- In 2004 when the Baltic Republics and several East European countries were going to join the EU, most EU countries put in place temporary restrictions on labour movements: not Sweden.

- In 2015, when the Syrian refugees arrived in large numbers, the right-wing Swedish Prime Minister, Reinfeldt, had a speech reminiscent of Angela Merkel’s famous s “Wir schaffen das” in which he urged the Swedes to “Open their hearts” to the refugees.

What about the ongoing Paradigm Shift, as the current government likes to label its policies? Can that be said to be cultural?

If anything, the current policies are contrary to what characterizes Swedish culture. They are neither compassionate, nor pragmatic, nor easy-going.

The ongoing paradigm shift is more likely the effect of a long-simmering and increasing frustration by parts of the population with the previous policies. The arguments are like those voiced in many other countries in Europe or North America.

Another point to argue that it is not cultural is that the Nordic countries are culturally quite similar. Yet immigration policies have differed greatly between the extremes with large differences in outcome: as mentioned, Sweden has 20% foreign-born whereas Finland has 7%. If culture were a decisive factor, they would have been more similar.

Although the policies have been quite consistent, there have been significant internal disparities regarding immigration attitudes. Regionally, the regions of Skåne and Blekinge, that were Danish until mid-1600s, have consistently exhibited more skepticism towards immigration. Local parties with explicit anti-immigrant agendas have a long-standing presence in these areas, and the current far-right party, the Sweden Democrats, has its roots in these two regions. Conversely, areas around Gothenburg and Stockholm have been consistently more welcoming to immigration.

And what would the policies have been if the Social Democrats had remained in power in 2022? As mentioned above, in 2015 the then Social Democratic Government changed tack on immigration. From a Merkel-like policy of ”Wir Schaffen das!” to a policy meant to align Sweden with the lowest immigration levels within the EU. If the earlier policies were aligned with the Swedish cultural profile, the shift certainly is not.

Contemporary incidents have also shaped the policies. Overall crime rates have been on a downward trend in Sweden for a long time, but fatal gang-related shootings have spiked significantly in the past 2-3 years, reaching unprecedented levels. Since the culprits are often from immigrant-dense suburbs, they have likely exacerbated public resentment towards immigration.

A counterforce may be that Sweden just like most European countries has a severe shortage of labor, both in qualified professions and unqualified. Businesses are urging the government not to impose too restrictive measures.

IV – Conclusion: In the case of Sweden, culture does not explain migration policies

Sweden’s migration is summarised as:

- 1850-1930: Emigration mainly driven by economic factors, not culture.

- 1930-1943: The shift is driven by the world economy and global politics, not culture.

- 1943-1970: The import of Labour was driven by the expansion of the economy and need for labor, not culture (except that more restrained and uncertainty-avoiding cultures might have opted for replacing labor with technology).

- 1980-2016: The large-scale politically driven immigration, partly explained by culture and the desire to help the less well-off.

- 2016-onward: The adoption of more restrictive policies to curb immigration, yet businesses having a very hard time finding the labor they need. Not in line with Swedish culture.

As indicated, only one period has anything like a cultural explanation – the 1980-2016 period.

Conclusions

Finally, the author finds that looking for cultural explanations for migration patterns might be overstating the importance of culture and understating the importance of economics and politics.

A reflection is that the impact of culture on migration is interesting to research. A Study by Mounir Karadja (Uppsala Universtiy) and Erik Prawitz (IFN) concluded that among emigrants from Sweden to North America in the 19 Century, there were an overrepresentation of people with individualist preferences. It also finds that the “communes” (the smallest administrative units) from where most migrants left had a stronger growth of Trade Unions and left-voting citizens. This implies that the more individualistic Swedes had a higher tendency to leave the country, resulting in more collectivist individuals remaining in the country.

In the same way, it is evident that the influx of 20% of new inhabitants to Sweden will impact its culture. Of course, it is impossible to foresee how, except that since Sweden is the most feminine culture in the world, as well as quite uncertainty tolerating and indulgent, it would not be surprising if these dimensions were to become less prominent over time.

Bio Philip Sjögren

Having studied at the Stockholm School of Economics, Philip Sjögren started his career as a is a diplomat in the Swedish Foreign Service. In 1995 he became a Management Consultant. First working on strategies with McKinsey and Company, and since 2000 working for various smaller consultancies in the areas of management development, corporate culture and national cultures. He is currently a partner with Stardust Consulting in Sweden.

His extensive consulting experience has enabled him to engage professionally in 40 countries. Philip is a native French and Swedish speaker, and is also fluent in English, German, and Spanish.

Literature:

Exit, Voice and Political Change: Evidence from Swedish Mass Migration to the United States, Journal of Political Economy (Karadja and Prawitz 2018).

The Swedish Theory of Love – Individualism and Social Trust in Modern Sweden (Henrik Berggren and Lars Trägårdh)

Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Third Edition (Geert Hofstede, Gert Jan Hofstede and Michael Minkov)

Notes:

[1] This number was claimed by Bernadotte himself. The action was later criticized as not in line with Red Cross ideals.

[2] Social Democrats (center left to left, in uninterrupted Government 1936-1976, as well as 1981-1988, 1991-2008, 2014-2022), Sweden Democrats (extreme right), Moderaterna (traditional right, historically the major right-wing party), Vänsterpartiet (literally the “left” Party, former Communists), Center Party (right of center, traditionally more agrarian, currently very liberal), Kristdemokraterna (increasingly right wing), Miljöpartiet (the green party) and Liberalerna (center right, traditionally urban).The

0 Comments