THE DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION (DEI) PARADOX:

HOW CAN WE RESPECT CULTURAL DIVERSITY AND, AT THE SAME TIME, BE IN LINE WITH OUR DEI POLICIES?

By Pia Kähärä and Valeria Rodríguez Brondo

Keywords: diversity, equity, and inclusion; cross-cultural management; high-performing teams

Synopsis

One of our Swedish clients, with a significant subsidiary in Russia, raised a question in a workshop about how to implement LGBTQ policy in the country when the national culture and law conflict with their diversity, equity, and inclusion policy. So, how to preach diversity, equity, and inclusion while understanding and respecting cultural differences? Are we facing a paradox? Are there ways to adapt the DEI concept to the local culture?

This is the inspiration for the article that follows.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are among the latest management concepts adopted by global companies on their way to building high-performing teams and organizations. This concept was created in the United States and quickly adopted by Western cultures, particularly in the Anglo-Saxon world in countries such as Great Britain, Australia, and Canada. [1]

In this sense, both the concept and the policies linked to it have a cultural bias and a conjunctural one, coming from the socio-cultural, demographic, and economic situation of the United States and other Western industrialized countries.

Since the realities worldwide are multiple and diverse, it would not be easy to believe that the Anglo-Saxon approach adapts and satisfies global needs. For example, DEI-related issues are different globally, as is the legislation. Also, the key concepts and values behind the DEI are understood and accepted differently, and the risks and taboos differ from country to country. Therefore, managers and employees do not see the relevance of DEI efforts in the same way in all locations. That’s why in this article, we will discuss the applicability of the key concepts of diversity, equity, and inclusion in non-Anglo-Saxon countries.

To achieve our goal, we will navigate through the basics of research about the high-performing teams (factors behind the value of DEI for companies) and DEI KPIs, get insights from cultural expert interviews worldwide about issues with DEI statements, and synthesize the findings with Hofstede’s 6D to explain what does and what does not culturally work in terms of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Finally, this article is intended for DEI professionals in global companies, DEI policy builders, managers running multi-place and multicultural organizations, DEI training program designers, and everyone interested in the subject.

INDEX

- Setting the Stage: The DEI Paradox in Today’s Global Business Environment

- Reframing DEI: A deep Dive into National Cultures

- Deciphering the cultural Assumptions Driving DEI: A global Perspective

- Unpacking the Paradox: Navigating Cultural Dimensions for Effective DE implementation

- The 7 Mental Images of National Cultures

- Rethinking DEI: A critical Examination of Key Statements from a Cultural Standpoint

- Measuring Success: Key Performance Indicators for Effective DEI implementation

- Looking ahead: Conclusive Insights and Future Directions for Global DEI Managers and Experts

- General recommendations

- Recommendations by cultural dimensions creating challenges for DEI initiatives.

- Unlocking the Potential: Navigating the Ease of Adopting DEI in Cultural Clusters

- Final reflections

Bibliography

1. Setting the Stage: The DEI Paradox in Today’s Global Business Environment

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) are among the latest management concepts adopted by global companies to build high-performing teams and organizations. However, as organizations operate globally, they increasingly face challenges related to DEI when working in different countries with distinct national cultures.

While the concept of DEI is gaining more attention to create a more inclusive and fairer workplace for employees and drive business success, achieving DEI in the workplace is not always straightforward.

Cultural differences can create significant barriers that affect how the concept is perceived and implemented in different countries. Our inspiration for this article came from our observations as both as DEI and intercultural consultants and trainers and from a specific Swedish client with a significant subsidiary in Russia, who raised a question in a DEI workshop about how to implement LGBTQ policy in the country when the national culture and laws conflict with their DEI policy.

This dilemma raises the question of preaching diversity, equity, and inclusion while understanding and respecting cultural differences. Are we facing a paradox? Are there ways to adapt the DEI concept to local culture?

This article explores the relationship between DEI and national cultures and provides cultural insights that organizations need to consider when implementing their DEI efforts globally.

To achieve our goal, we will navigate through the basics of research about high-performing teams, discuss the unstated and cultural assumptions behind DEI principles, and provide examples of some DEI statements widely used in the DEI literature and training by highlighting their cultural assumptions.

We will use our experiences as intercultural experts to synthesize the findings with Hofstede’s 6D model (2010) [2] and Huib Wursten’s 7 Mental Images (2019) [3] tool for cultural clustering, as well as the qualified opinion of several intercultural experts from around the world, to explain what may culturally work and what may not work in different countries.

With the example of our Swedish client as inspiration, we will illustrate the challenges organizations may encounter in their DEI implementation, particularly in certain cultural clusters. Overall, this article highlights the importance for managers and DEI professionals to understand the relationship between DEI and national cultures and to adapt their policies and practices to local cultural contexts.

2. Reframing DEI: A Deep Dive into National Cultures

Firstly, it is beneficial to discuss the DEI concept itself for understanding the business case behind Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in organizations. Several studies argue that DEI is not only the right thing to do but also a business imperative that can lead to improved performance, decision-making, and innovation.

One of the seminal studies supporting the business case for diversity is the 2015 Google study on teams, which found that teams with higher levels of psychological safety (a key component of DEI) were more productive and innovative. [4]

Amy Edmondson (2018), a professor at Harvard Business School, has also contributed to this framework through her research on psychological safety and high-performance teams. In her book “The Fearless Organization,” [5] she argues that creating a psychologically safe environment where individuals feel comfortable speaking up and taking risks is critical for achieving high performance and innovation.

Another important perspective is the work of Timothy R. Clarke (2020) [6], who has studied the impact of diversity on decision-making. In his 2017 book “The Four Stages of Psychological Safety,” Clarke argues that diverse teams can make better decisions than homogeneous teams, but only if they have a high level of psychological safety that allows for open communication and respectful disagreement.

While these theories originate from Anglo-Saxon countries (mainly US), they have relevance across different cultural contexts, as it is natural that groups come up with better decisions than individuals alone. However, the adoption of DEI principles which contain cultural values and unstated assumptions from their cultural origins, can face cultural barriers that vary across different countries

2.1 Deciphering the Cultural Assumptions Driving DEI: A Global Perspective

To understand the cultural origins of DEI, we examine key assumptions that underpin the concept. These include respect for all, the value of differences, humanity and empathy, and justice and fairness. As we will explain, these values stem from cultural dimensions such as low power distance, high individualism, and low uncertainty avoidance.

Respect for all: This is a fundamental value of DEI. It implies that everyone, regardless of their background, deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. This value stems from societal values of low power distance and egalitarianism.

Value of differences: This principle suggests that diversity is not just a box to be checked but a source of strength and creativity. It’s the belief that different people with different perspectives can lead to richer discussions, more innovative solutions, and a more holistic understanding of problems. This value stems from high individualism and low uncertainty avoidance.

Humanity and empathy: The focus on the fact that every individual has unique experiences and challenges, and respecting those experiences, empathizing with them, and being willing to learn from them, is a core unspoken value that reflects individualistic societies.

Justice and fairness: The desire for a more just and fairer world is at the heart of DEI. This involves confronting and rectifying past and present injustices and working towards a society and organizations where opportunities and resources are distributed fairly. This value also reflects high individualism and low power distance.

As we will see, the Hofstede model and the 7 Mental Images of National Cultures model can provide valuable insights for DEI professionals and managers. By analyzing them together, we better understand how the cultural dimensions shape attitudes and behaviors towards DEI and what kind of dimension combinations create the most challenges for adopting the DEI principles. In addition, this analysis can help predict where organizations may encounter the most challenges when implementing their DEI efforts.

2.2 Unpacking the Paradox: Navigating Cultural Dimensions for Effective DEI Implementation

In this article, we delve into the impact of the initial four dimensions of the Hofstede 6D model on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives. Widely recognized as a comprehensive and extensively studied scientific framework for understanding cultural variances, the model is the foundation for exploring the intersection between cultural dimensions and DEI efforts.

Power Distance (PDI, low or high )

Power distance (PDI) is the first cultural dimension in Hofstede’s model, which measures the extent to which members of a society accept and expect power differences among individuals. Egalitarian societies, which comprise only about 15% of countries worldwide, generally uphold universal human rights and value equality for all individuals. In these societies, democratic principles are highly prized, and leaders often seek input from others before making decisions. Communication is bidirectional, with information flowing from the top down and bottom up. People are encouraged to speak up and take initiative, and it is acceptable to disagree with managers.

In contrast, hierarchical societies (PDI+), representing around 85% of countries worldwide, tend to have a different cultural approach. Not all individuals are viewed as equal in these societies, and leaders’ opinions carry more weight. In this context, adherence to leaders’ views is prioritized, with communication mainly flowing top-down, and individuals are often discouraged, if not penalized, from expressing dissent, voicing their opinions, or saying “no” to authority.

When DEI initiatives are introduced, employees in high power distance cultures may be skeptical about the feasibility of these principles. Given that authority is highly respected in such cultures and questioning authority is seen as disrespectful, it may be necessary to adopt a different approach to foster a psychologically safe environment than in egalitarian cultures (PDI-).

Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV)

The second dimension of Hofstede’s model is individualism (IDV+) versus collectivism (IDV-), which explains the individual’s relationship with a group. In individualistic cultures, people are expected to look after themselves and their immediate family only, with no group intervention in individuals’ choices. On the other hand, in collectivistic cultures, people belong to in-groups or collectives that are supposed to look after them in exchange for their unconditional loyalty.

It’s worth noting that individualistic countries, which culturally prioritize independence and individual freedom of expression reflecting the key values behind DEI, represent only about 15% of the countries in the world. In these countries, the individual opinion prevails over group opinion, and individuals make their own decisions about their lives. Task completion precedes relationships governed by agreements rather than moral grounds. Expressing opinions that differ from the group’s is acceptable, and conflicts of opinion are expected.

In collectivistic countries, where interdependence and group harmony by loyalty are prioritized, the in-group’s opinion is valued more than the individuals’. In these societies, relationships are the most important assets in people’s lives and are often based on moral grounds. Expressing opinions that differ from the in-group’s can be seen as causing shame for the whole group, and a reason for penalty (exclusion), and thus, conflicts of opinions are often avoided. Introducing DEI programs in collectivistic societies may require a different approach since individuals are expected to prioritize the group’s opinion over their own, and expressing dissent can be viewed as going against the group’s interests.

Masculinity vs. Femininity (Assertive vs. Consensual)

Hofstede’s third dimension, Masculinity (MAS), measures the sources of motivation across different cultures rather than referring to traditional masculine or feminine characteristics.

Masculine/assertive (MAS+) cultures prioritize competition, with the strongest opinion or the winner taking precedence. People are ranked based on success; emotions should be hidden or controlled. Material success is often the ultimate motivational factor. As a result, they may be less receptive to DEI initiatives focusing on softer approaches like collaboration and well-being.

On the other hand, feminine/consensual (MAS-) cultures value collaboration, negotiation, and decision-making that considers all opinions. No individual is considered better than others; the emphasis is on hearing the views of all stakeholders, including minorities and workers, and often compromising. These cultures prioritize the quality of life and well-being, accepting weaknesses and vulnerability as natural human traits, and have a stronger tendency to provide equity for the less unfortunate.

Understanding and respecting these cultural differences is essential to creating successful DEI programs that meet the needs of both ends of this dimension.

Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI)

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) measures the degree to which members of society feel threatened by ambiguity and uncertainty and their tendency to avoid or control such situations.

Countries with a lower UAI score are considered relaxed and pragmatic, embrace uncertainty as a part of life, value flexibility, and prioritize uniqueness. They are open to change, unafraid of differences, and see mistakes as opportunities to learn and grow. In these cultures, freedom of expression is encouraged, and individuals feel comfortable sharing different opinions, making it easier for organizations to promote diversity and inclusion.

On the other end of the UAI scale are anxious/analytical cultures that prefer to avoid uncertainty and ambiguity by exerting control over their environment. These cultures are risk-averse (to unknown risks) and may resist change initiatives, viewing failure as a negative outcome. Freedom of expression may be restricted in these cultures, and demonstrating vulnerability can be challenging. This could make it more difficult for organizations to promote diversity and inclusion, as individuals may be less likely to express different opinions or embrace change.

Therefore, organizations operating in anxious/analytical cultures may need to employ strategies that make individuals feel safer sharing their opinions and promote a culture of openness and inclusivity.

2.3 The 7 Mental Images of National Cultures

For our study, we also incorporate the 7 Mental Images of National Cultures model, developed by Huib Wursten (2019), to further examine the intricacies of cultural diversity. This model builds upon the Hofstede framework, grouping approximately 200 cultures into seven distinct clusters based on their scores in the four key dimensions we mentioned. By delving into the interplay between these dimensions, we gain a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics that influence cultural interactions.

The clusters are as follows.

Contest (‘winner takes all’): Competitive cultures with low PDI, high IDV, high MAS, and relatively weak UAI. Examples include Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and the US.

Network (‘consensus’): Highly individualistic and feminine cultures with low PDI, where everyone is involved in decision-making. Examples are Scandinavia and the Netherlands.

Well-Oiled Machine (‘order’): Individualistic societies with low PDI and strong UAI have carefully balanced procedures and rules but not much hierarchy. Examples are Austria, Germany, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and German-speaking Switzerland.

Solar System (‘hierarchy and standardized job descriptions’): Hierarchical but individualistic societies. Examples are Belgium, France, Northern Italy, Spain, Poland, and French-speaking Switzerland.

Pyramid (‘loyalty, hierarchy, and implicit order’): Collectivistic cultures with high PDI and strong UAI. Examples are Brazil, Colombia, Greece, Portugal, Arabian countries, Russia, Taiwan, South Korea, and Thailand.

Family (‘loyalty and hierarchy’): Collectivistic cultures with high PDI, where powerful in-groups and paternalistic leaders can be observed. China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Singapore are examples.

Japan is the seventh mental image (‘dynamic equilibrium’) because of its unique combination of dimensions not found in any other Mental Image. Japan has a mid-PDI, a mid-IDV, a very strong UAI, and a high MAS score.

The 7 Mental Images of National Cultures model can be useful for truly global organizations promoting DEI to understand in which clusters they might encounter more implementation challenges and adapting their strategies accordingly. For example, in cultures combining high PDI and low IDV, such as China or Brazil, hierarchical structures and loyalty to in-groups are highly valued, and people expect and respect paternalistic leadership style. Understanding these cultural differences can help organizations adapt their ways of creating a more inclusive and effective work environment.

Finally, understanding cultural differences is crucial for successful cross-cultural interactions in personal and professional settings. Individuals and organizations can improve cross-cultural communication and collaboration by developing cultural competence, leading to more successful outcomes in a globalized world.

3. Rethinking DEI: A Critical Examination of Key Statements from a Cultural Standpoint

In this article, we analyzed common statements used in DEI literature and training to provide executives and DEI professionals with practical examples of how different cultures see them. By exploring the cultural assumptions of these statements, we gained insight into their potential effectiveness. Additionally, we consulted with experts from different cultural clusters – Contest, Network, Solar, Pyramid, and Family – to better understand how these statements might be received in their respective cultures. Finally, we will detail four specific DEI statements and analyze them.

Statement 1: “Everyone in the organization should have a voice; feel welcome to speak up and be listened to. They can do it knowing they will not be punished or humiliated, nor will it harm their career.”

The underlying assumption of this statement is that by fostering a workplace culture that values and encourages diverse perspectives and open communication, organizations can benefit from improved collaboration, innovation, and employee morale.

Cultural assumptions behind the statement:

- Low Power Distance: The statement assumes a national and organizational culture with low power distance, where hierarchical differences are minimized, and everyone, regardless of rank or status, is encouraged to voice their thoughts and opinions. In such cultures, subordinates are seen as independent entities rather than followers, and open communication is encouraged.

- Individualism: The focus is on the values characterizing individual cultures: personal freedom of expression and speaking up without fear of punishment.

- Femininity: The focus on a respectful, non-hostile environment where everyone (regardless of their earned status, experience, etc.) is encouraged to share their ideas aligns more with ‘feminine’ cultures, prioritizing cooperation, consensus and care for all members of the organization. Feminine culture values like modesty, cooperation, and mutual respect over assertiveness and competition support the expectation that individuals will not be punished, humiliated, or experience harm to their career for speaking up.

- Low Uncertainty Avoidance: This statement reflects an acceptance of different views and ideas, which is more typical of cultures with low uncertainty avoidance. These cultures are comfortable with ambiguity and open to change.

In clusters characterized by low Power Distance Index (PDI), high Individualism (IDV), and low Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI), the adoption of DEI concepts appears relatively straightforward, as these clusters have a history of embracing such ideas. However, in pyramid countries with higher PDI and more hierarchical structures, accepting these concepts is hindered by the fear of repercussions and limited freedom of expression. Similarly, in the Family cluster, where preserving “face” holds significant importance, individuals may hesitate to voice their opinions if it risks losing face.

Power and hierarchy hold significance here and the consequence of living within a hierarchical structure is often punishment. Fear becomes intertwined with the notion of respect. While the influence of foreign companies has slightly altered the market landscape, if a director lacks the motivation for personal growth, a prevailing company culture often adheres to the mentality of ‘I’m the boss, and you’re a fool: intercultural consultant, Russia (Pyramid Cluster).

Overall, cultural differences significantly affect how this statement is viewed and can be adopted within different organizations and countries.

Statement 2: “Everyone, regardless of their background, and relationship with the power holder, will be treated similarly and given equal opportunities in the organization.”

The key unstated assumption behind this DEI statement is that providing equal opportunities and fair treatment to all employees, irrespective of their background or relationship with power holders, leads to a more inclusive, equitable, and successful organization.

Cultural assumptions behind the statement:

Low Power Distance: This statement assumes a small power distance culture where hierarchy is less important, and everyone is seen as having equal rights. In such cultures, the relationship with the power holder doesn’t determine one’s opportunities, and everyone is entitled to fair treatment, regardless of their status or position in the organization.

Individualism: The emphasis on equal rights and opportunities for all individuals, regardless of their background (relationship with power holders, etc.), aligns with individualistic cultures. In these cultures, personal achievements and individual rights are highly valued.

Femininity: The focus on equal treatment and opportunities for all organization members, irrespective of their background, aligns with ‘feminine’ cultures, where social equality, equity, cooperation, consensus, and quality of life are highly valued.

Low Uncertainty Avoidance: The statement implies a willingness to accept and embrace diversity in all its forms, typically associated with cultures with low uncertainty avoidance. Such cultures are more comfortable with change, diversity, and ambiguity.

Countries with low PDI and high IDV, such as the Contest, Network, and Machine countries, tend to have a more egalitarian view and are more receptive to the idea of treating everyone equally. However, even in these countries, there are challenges in overcoming traditional attitudes and practices.

In contrast, countries with high PDI and UAI, such as Pyramid and Solar System, face significant challenges in adopting this statement. Hierarchical and patriarchal cultures make it difficult to challenge traditional attitudes and practices. In high PDI societies, it is crucial for the power holder to lead the way in demonstrating that equal treatment for all is acceptable in the organization, as noted in the Family cluster.

The idea behind the statement can be adopted with a change here. A high PDI society requires the leader to want equal treatment for all. Therefore, it must be driven from the top, i.e., from the power holder, to let everyone know it is acceptable. Intercultural consultant, Hong-Kong (Family Cluster).

This idea is easy to adopt. I agree and appreciate this statement here. Germany is characterized by a lot of immigrant influence, for example. Intercultural consultant, Germany (Machine Cluster)

Overall, these responses demonstrate that the concept of equal treatment and opportunities for all is a complex and challenging issue that requires careful consideration in DEI implementation globally.

Statement 3: “Leaders should model and act with vulnerability to encourage others to do the same.”

The key unstated assumption of leaders showing vulnerability in DEI practices is that such openness fosters trust, empathy, and inclusivity, creating a psychologically safe and supportive work environment that leads to better performance.

Cultural assumptions:

- Low Power Distance: This statement assumes a culture with low power distance, where hierarchy is downplayed, and leaders are seen as equals rather than superiors. In such cultures, leaders displaying vulnerability can be perceived as a way to build trust within the team.

- Individualism: The encouragement for leaders to model vulnerability can also reflect individualistic cultures, where the emphasis is placed on self-expression and personal freedom to express emotions without fear of judgment or repercussions.

- Femininity: The suggestion that leaders display vulnerability aligns more with ‘feminine’ cultures in Hofstede’s model. These cultures value traits such as sensitivity, cooperation, and empathy, which can be associated with vulnerability and perceived as a way to build trust.

- Low Uncertainty Avoidance: The idea that leaders should show vulnerability implies a comfort with uncertainty and ambiguity, a characteristic of cultures with low uncertainty avoidance. These cultures are more accepting of different behaviors and less ruled by strict norms and conventions.

Power Distance and Masculinity versus Femininity dimensions play a significant role in adopting vulnerability in leadership. In high PDI cultures, leaders are not expected to show vulnerability. Similarly, in masculine cultures, vulnerability is not considered a desirable quality for a leader. National culture and personality traits also play a role in the adoption of vulnerability in leadership. This statement may be one of the most challenging to implement in the Machine and Contest clusters, given their high Masculinity (MAS) scores and in Pyramid, Solar and Family clusters due to their high PDI scores.

In MAS+ countries, it is not easy to show one’s vulnerability, as people prefer to follow the strong. But, on the other hand, vulnerability is easier to show in MAS- countries where people more instinctively follow ‘the ones like us.

– Intercultural expert, USA (Contest Cluster).

If a CEO displays vulnerability, their brave behavior can garner admiration from some individuals, while others may perceive it as a weakness, potentially jeopardizing their position as a respected CEO. – Intercultural expert, Russia (Pyramid Cluster).

We do not have a culture of accepting errors. Being vulnerable is considered not good enough for the role. The leader should have all the answers. – Intercultural expert, Italy (Solar Cluster).

Statement 4: “In our organization, people are respected for their ability to innovate and have permission to challenge the status quo.”

Implicit in this statement is the assumption that encouraging employees to innovate and challenge the status quo promotes diversity of thought, which can lead to improved problem-solving, decision-making, and overall organizational performance.

Cultural assumptions behind the statement:

- Power Distance Index (PDI): In cultures with low power distance, challenging the status quo and innovating are often encouraged, as these cultures value equality and decentralization of power.

- Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV): Individualistic cultures, which value personal achievement and freedom, are often more open to innovation and challenging the status quo.

- Masculinity (MAS): Masculine cultures, which value achievement and heroism, might particularly respect and encourage innovation as it can lead to competitive advantage.

- Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI): Cultures with low uncertainty avoidance are generally more comfortable with ambiguity and thus may be more open to innovation and challenging the status quo.

It seems that most of the experts agree that promoting vulnerability and celebrating mistakes are difficult to adopt in many cultures, while the idea of respecting individuals for their ability to create value and innovate is easier to adopt in cultures with low PDI and high IDV, and where change is generally accepted, like in Contest and network clusters. However, even in these cultures, there may be challenges in putting these ideas into practice, especially in traditional corporate environments or hierarchical societies. In contrast, cultures with high UAI (Machine, Pyramid and Solar clusters) may resist change or innovation and may not have a culture of admitting mistakes or vulnerability.

Initiative is punishable! -proverb, you can challenge and have the ability to innovate but from a certain position in the hierarchy. Intercultural Expert, Russia (Pyramid cluster)

Depending on the industry, people (grassroots) are not welcome to change the status quo unless directed by top-down. I think it is still difficult to be an innovative person in a rather traditional corporate environment. Intercultural Expert, Germany (Machine Cluster)

Considering these cultural factors when implementing DEI initiatives and leadership practices is important.

To conclude, each cultural expert provided their perspective on the forms of diversity that may face challenges in being accepted in their respective countries. It is important to acknowledge that diversity and inclusion are complex and sensitive topics that require careful consideration and respect for different perspectives.

The cultural experts from the Contest, Machine and Solar Cluster did not identify any form of diversity they believed could not be accepted in their national culture. This suggests these countries may have a relatively more inclusive approach to diversity.

In contrast, the cultural experts from Pyramid and Family clusters noted that sexual orientation or certain ethnicities might face challenges in being accepted in their respective countries. These responses may suggest that these countries may have more traditional or conservative attitudes towards certain forms of diversity. The experts from the Family cluster noted that equal treatment might be harder to achieve unless those in power are committed to making it happen.

Overall, these statements show that national and organizational culture, as well as individual personality traits, play a significant role in the adoption of DEI practices. Therefore, companies must consider these cultural factors when developing and implementing their DEI initiatives to ensure they are effective and culturally appropriate.

4. Measuring Success: Key Performance Indicators for Effective DEI Implementation

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) have a transformative role in guiding organizations to foster and measure the impact of their DEI initiatives, thereby creating more inclusive, equitable, and culturally sensitive workplace environments that ultimately lead to heightened innovation and competitive advantage. In addition, they help identify global and local improvement areas for the organization and promote accountability among leaders and teams in fostering diverse and inclusive workplace environments.

DEI KPIs can be derived from multiple sources, encompassing industry standards, regulatory guidelines, and the organization’s internal objectives. For instance, the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) [7] presents a DEI maturity model delineating five phases of DEI growth. It proposes relevant KPIs for each phase, such as diversity representation metrics, employee engagement survey results, and training participation rates.

Within the scope of our article, DEI KPIs serve as pivotal tools for organizations aiming to foster more diversity and inclusion. Through monitoring and evaluating DEI initiatives, organizations can ensure the implementation of significant and long-term changes while pinpointing areas that need improvement. Additionally, DEI KPIs can assist organizations in tailoring their DEI approaches worldwide to align with the local cultures, incorporating cultural nuances and values that influence people’s perception of and reaction to diversity and inclusion. Finally, for meaningful change in different locations, taking local teams along for KPI planning is crucial, as DEI challenges and national cultures differ across countries and organizations.

In conclusion, DEI KPIs are essential for promoting DEI actions in organizations, but customizing them to fit local cultural contexts is necessary. In addition, organizations need metrics to establish and measure objectives related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, which helps them cultivate workplaces that are more inclusive and equitable and conducive to innovation, creativity, and collaboration, which enable high performance and competitive edge both globally and locally.

5. Looking Ahead: Conclusive Insights and Future Directions for Global DEI Managers and Expert

5.1 General recommendations

- Consider the local level of acceptance of specific DEI topics, using the cluster model to inform decision-making. Involve the local teams in the discussions.

- Incorporate intercultural experts to assist in adapting DEI policies and training to local environments while benefitting from cultural models.

- Tailor DEI KPIs, policies, and training approach and contents to local cultures and legal environments, considering the following cultural dimensions.

5.2 Recommendations by cultural dimensions creating challenges for DEI initiatives.

- PDI: In hierarchical countries, DEI implementation may need to emphasize respect for authority. Involve local top management in the process to create assurance for all levels of the organization.

- IDV: Emphasize the group interests in cultures with high collectivism. Create a safe space for expressing opinions to benefit from the diversity of thought, which often does not come naturally there. The manager’s role is central, as well.

- MAS: In assertive cultures, focus on promoting the value of DEI in achieving success and getting a competitive advantage. Promoting diversity may be perceived as a threat to the dominant group’s success. In consensual cultures, emphasize the importance of giving opportunities and support for all to create well-being, listening to all stakeholders, and promoting a culture of empathy and vulnerability.

- UAI: In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, clearly and frequently communicate DEI initiatives’ purpose and scientifically proven benefits to reduce uncertainty by creating a sense of familiarity and understanding. Use culturally relevant examples to explain concepts and expected outcomes. High uncertainty avoidance cultures may find sudden, large-scale changes disconcerting. Therefore, consider implementing DEI initiatives gradually, allowing time for individuals and teams to adapt to the changes.

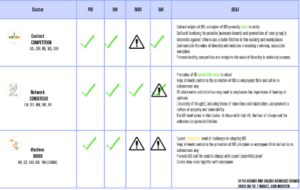

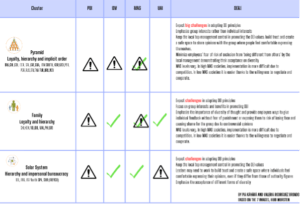

5.3 Unlocking the Potential: Navigating the Ease of Adopting DEI in Cultural Clusters

Due to their unique cultural dimension combinations, cultural clusters pose different challenges in how easy it may be to adopt the principles of DEI.

The main principle managers should understand is that due to cultural reasons, adopting the principles of DEI and implementing them successfully in the global setting will likely be challenging. The following tables illustrate the level of challenges per cluster. Contest and Network clusters will be easier because they’re egalitarian, individualist, and pragmatic, while Machine will be moderate due to their high uncertainty avoidance and assertiveness.

It is worth noting that the biggest global cluster, the Pyramid, contains a cultural dimension combination that seems the most counter-counterproductive and requires the biggest efforts for successful DEI implementation. Also, in Family and Solar Clusters, we encounter difficulties due to hierarchy and collectivism in the first one and the complexity of high-power distance and individualism plus uncertainty avoidance in the second.

6. Final reflections

To summarize, we have explored the paradox of implementing DEI policies in countries with distinct cultural backgrounds, as exemplified by the case of a Swedish company’s subsidiary in Russia. We have emphasized the importance of adapting DEI policies to align with local cultures while maintaining consistency with the overarching DEI goals of the organizations. To achieve this balance, companies must conduct thorough research, engage intercultural experts and local champions, create safe spaces for open dialogue, and establish measurable KPIs.

However, even with all these efforts, companies may still face the challenge of navigating conflicting cultural values and local laws when implementing DEI policies. This is where the paradox lies. On the one hand, DEI policies can improve business outcomes, foster innovation, and attract top talent. On the other hand, however, these policies may clash with deeply ingrained cultural values, norms, and laws. The challenge then becomes how to respect cultural diversity while promoting DEI principles, which may be perceived as foreign or even threatening.

To address this paradox, we propose a reframing of the issue. Instead of viewing DEI as a set of policies to be implemented, we should view it as a mindset to be cultivated. As a result, organizations can foster a culture of empathy, vulnerability, and open dialogue that transcends cultural barriers and promotes inclusivity. This requires a willingness to listen, learn, and adapt to local contexts while staying true to overarching DEI principles. In this way, organizations can promote diversity and inclusion and foster a culture of innovation, collaboration, and high performance that transcends cultural boundaries.

In conclusion, the DEI paradox is a complex and nuanced issue requiring a multifaceted approach. By adapting DEI policies to local cultures, fostering a culture of empathy and open dialogue, and reframing DEI as a mindset rather than a set of guidelines, companies can navigate cultural differences while promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion. Ultimately, by embracing this mindset to listen, learn, and adapt to local contexts, companies can transcend cultural boundaries and foster a truly global culture of inclusivity and innovation.

Bibliography

JSyeda and O ̈ zbilginb (2009), “A relational framework for international transfer of diversity management practices”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 20, No. 12.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). “Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind”. Berkeley: McGraw Hill

Wursten, H (2019). “The 7 Mental Images of National Culture: Leading and Managing in a Globalized World”. Finland: Hofstede Insights.

Edmondson, Amy (2018) “The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth”, Harvard Business School

Timothy R. Clarke (2017) “The Four Stages of Psychological Safety” Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2020

Notes:

[1] JSyeda and O ̈ zbilginb, “A relational framework for international transfer of diversity management practices”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 20, No. 12, December 2009, 2435–2453.

[2] Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. Berkeley: McGraw Hill

[3] Wursten, H (2019). The 7 Mental Images of National Culture: Leading and Managing in a Globalized World. Finland: Hofstede Insights

[4] What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html?smid=pl-share

[5] Edmondson, Amy (2018) The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth, Harvard Business School

[6] Timothy R. Clarke (2017) “The Four Stages of Psychological Safety” Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2020

[7] DEI Metrics 2021 SHRM partnered with Harvard Business Review Analytic Services and Trusaic to conduct a study on the extent to which diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) is a strategic priority for organizations. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/pages/dei-metrics-.aspx

0 Comments