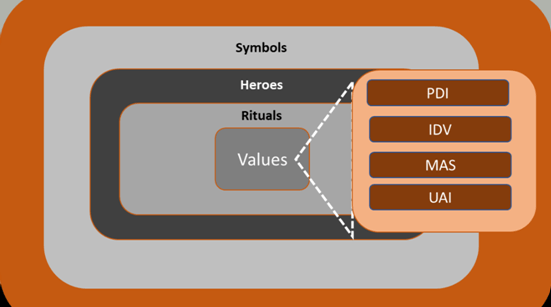

Short description of the four layers of Culture.

Drs. H. Wursten The Netherlands

Tel: (+31) 653613359. e-mail: huibwursten@gmail.com

- Culture consists of different layers. Some of the layers are superficial and subject to change. Others are more fundamental and consistent over time.

The first layer: Symbols On the outermost layer, the superficial layer of culture, symbolic behavior, one can see worldwide trends. Everywhere, one can find brands like NIKE, Coca-Cola, Marlboro and McDonalds. Even in a tea-drinking nation like Japan, one can find the American coffee chain Starbucks. This has led some to the possible observation that the world is Americanizing. This effect cannot be denied. However, the Americanization of the world is at a superficial level of behavior. There is an all-human tendency to imitate success, and it is certainly true that the US has been very successful in the last fifteen years in terms of economic power. As a result, people everywhere try to imitate this success on a symbolic level. But if one scratches at the surface, other preferences are found. Interestingly enough, this identification on this level is changing every 15 years or so. Around 1985, it was not the US that was the most powerful economic power, but Japan. In the whole world, people were trying to imitate the Japanese. All organizations, including American, were trying to introduce quality circles to improve what they were doing. Around that time, the CEO of the Dutch multinational Philips said in a worldwide address to his personnel:” We have to be more like the Japanese if we want to survive in the international competition. “

If one goes back a little more in time, to the late 50’s, Germany had that position. Because of the “economic miracle” in Germany, everybody was trying to introduce the so-called DIN (German Industry Norm) norm in his or her own society.

The second layer, heroes and anti–heroes, is a little bit less superficial.

This is a level where identification models are used to show how to be successful and examples showing what not to do. In the advertising world, the agencies learned it the hard way. The way to promote products, services, etc. in, for instance, Germany, where people’s interest is attracted by using expert information, should be done in a different way than in the UK, where humor is the way to catch the viewer, or France, where style and elegance are the key focus points or the Netherlands, where advertisements should stress the anti-heroes.

One example about reward systems: in the US, it is very effective to reward individual performance with a portrait on the wall: being “employee of the month” makes you a hero. In a country like Denmark, being appointed “employee of the month” is the biggest punishment one can get. It makes this person the bait of biting sarcastic jokes of their colleagues for the rest of their existence.

The third layer of culture, Rituals, is even more consistent. An example of a ritual we all know about is to have meetings. In the whole world, people have meetings. But what one expects a meeting to be is different from culture to culture. In some cultures, a meeting is a place to discuss. In other cultures, it is a platform for the Boss to communicate decisions to others. The effects can be very strange if people from different cultures have meetings together without being aware of these differences.

The deepest layer of culture is Values. Professor Geert Hofstede carried out fundamental research into the dominant values of countries and the way in which they influence behavior in organizations. Original data were based on an extensive IBM database for which, between 1967 and 1973, 116,000 questionnaires were used in 72 countries and in 20 languages.

Analyzing his data, Hofstede found four value clusters to be the most fundamental in understanding and explaining the differences in answers to the single questions. The results were validated against about 40 cross-cultural studies from a variety of disciplines. Hofstede gave scores for 56 countries on these dimensions. Later research partly done by others has extended this to around 160 countries. The combined scores for each country explain variations in the behavior of people and organizations. The scores indicate the relative differences between cultures.

Hofstede identified four main dimensions of national culture: power distance (PDI), individualism/collectivism (IDV), masculinity/femininity (MAS), and uncertainty avoidance (UAI)

A short description of the four dimensions.

Power distance is the extent to which less powerful members of a society accept that power is distributed unequally. In large power-distance cultures, everybody has his/her rightful place in society, there is respect for old age, and status is important to show power. In small power-distance cultures, people try to look younger and powerful people try to look less powerful.. People in countries like the US, Canada and the UK score low on the power-distance index and are more likely to accept ideas like empowerment, matrix management and flat organizations. Business schools around the world tend to base their teachings on low power-distance values. Yet, most countries in the world have a high power-distance index.

Individualism versus `Collectivism In individualistic cultures people look after themselves and their immediate family only; in collectivist cultures, people belong to “ingroups” who look after them in exchange for loyalty. In individualist cultures, there is more explicit verbal communication,In collectivist cultures, communication is more implicit.

Masculinity versus Femininity. In masculine cultures, the dominant values are achievement and success. The dominant values in feminine cultures are caring for others and quality of life. In masculine cultures measuable performance and achievement are important. Status is important to show success. Feminine cultures have a people orientation, small is beautiful, and status is not so important.

Uncertainty avoidance is the extent to which people feel threatened by uncertainty and ambiguity and try to avoid these situations. In cultures of strong uncertainty avoidance, there is a need for rules and formality to structure life. Competence is a strong value resulting in belief in experts, as opposed to weak uncertainty-avoidance cultures with belief in practitioners. In weak uncertainty-avoidance cultures, people tend to be more innovative and entrepreneurial.

How consistent are these values?

The question is if these values and the scores of countries are changing over time.

It’s good to look at the findings of other research replicating Hofstede’s research:

– A Danish scholar, M. Søndergaard, found 60 of these (sometimes small-scale) replications. A meta-analysis confirmed the four dimensions and the scores of countries.

– Another replication was carried out by including Hofstede’s questions in the EMS, the European Media & Marketing Survey. A research survey of print media readership and TV audience levels within the upscale consumer group in Europe (EU, Switzerland and Norway), (1996/1997). The country scores found in EMS were similar to those found 20 years earlier and were particularly strong when explaining diversity in consumption and ownership of products as measured in EMS.

– Marieke de Mooij, in her analysis of the findings, states: “Although there is evidence of convergence of economic systems, there is no evidence of convergence of peoples’ value systems. On the contrary, there is evidence that with converging incomes, people’s habits diverge. More discretionary income will give people more freedom to express themselves and they will do that according to their own specific values of national culture. National culture influences, for example, the volume of mineral water and soft drinks consumed, ownership of pets, of cars, the choice of car type, ownership of insurance, possession of private gardens, readership of newspapers and books, TV viewing, ownership of consumer electronics and computers, usage of the Internet, sales of video-cassettes, usage of cosmetics, toiletries, deodorants, and hair care products, consumption of fresh fruit, ice cream, and frozen food, usage of toothpaste and numerous other products and services, fast-moving consumer goods and durables. These differences are stable or become stronger over time. Culture’s influence is persistent cultural values are stable and with converging incomes, they will become more manifest.” (Italics by the author)

-The latest major repeat research by Beugelsdijk et al. in 2015 found that the scores of 2 ‘Dimensions’ are very slowly changing across the board. Everywhere the scores for power-distance are getting lower, the scores for Individualism are getting higher. The relative distances between countries are, however, not changing. That is, worldwide, we are moving in cohorts. See: Beugelsdijk, S., Maseland, R. and van Hoorn, A. (2015), Are Scores on Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture Stable over Time? A Cohort Analysis. Global Strategy Journal, 5: 223–240. doi: 10.1002/gsj.1098

Culture is consistent but not static

The problem is that a great many people don’t recognize these ‘gross group’ descriptions as having an influence and being consistent over time. On average, people tend to feel: “I am very different from my parents, and my grandparents are very different from my parents”. The reason for this ‘true’ observation is that usually, the visible aspects of culture are compared. In so doing, it appears to be easy to establish that the clearly visible behavior of the present generation is different from the behavior of past generations.

Saying that culture is consistent does not imply that the behavior is consistent. Our parents and grandparents behaved differently because they lived in totally different conditions. Who had to deal with issues such as globalization, the European Union, the Internet, mobile telephones, etc., fifty years ago?

The world is changing rapidly, and we are being forced to adjust to these changes and to develop new behavior. However, the development of this new behavior is constantly influenced by the set of collective preferences.

If people become aware of themselves in relation to their environment, they are able to make new choices. But when examining history, we find that the choices people make are by no means random. We recognize regularities, ‘scripts’, which can be traced back to deeply rooted values that give direction to their (re) actions

Hofstede defines culture as the collective, mental programming that distinguishes one group or category of people from another. This programming, or mindset, influences patterns of thinking, which are reflected in the meaning people give to the different aspects of their lives and therefore, help shape the institutions of a society.

This does not mean that everyone in a particular society is programmed in exactly the same way. There are considerable individual differences. But when fundamental values of various societies are compared, ‘majority preferences’ are found to exist, which recur again and again as a result of the way children are brought up by their parents and the educational system. And when we examine how societies organize themselves, these majority preferences turn out to have a modifying influence at both micro and macro levels. They appear to have an influence on the ways in which good leadership is defined; on how the decision‑making process is structured, as well as on the way people monitor how policies are implemented. In short, everything that has to do with organizational behavior.

Culture is not the same as identity

Almost everybody feels an emotional attachment to one group or another. Sometimes, it’s a nation or a region. Sometimes it’s a football club. It’s a known fact that a club like Manchester United has fan clubs all over the world, wearing the Manchester shirts and identifying with the team. Sometimes, these feelings of identification are quite strong, leading to the infamous fights between supporters of the different clubs.

Don’t confuse this with culture. In the words of Hofstede (6): “Identities consist of people’s answers to the question: where do I belong? They are based on mutual images and stereotypes and on emotions linked to the outer layers of the onion…Populations that fight each other on the basis of their different” felt” identities may very well share the same values. Examples are the linguistic regions in Belgium, the religions in Northern Ireland, and tribal groups in Africa.”

Sometimes, it’s confusing that people willingly try to create identities different from their environment in spite of sharing the same values. I mention here two of these possible reasons:

- The sour grapes

This label is related to the fox in Aesop’s fable, who tried to seize an attractive bunch of grapes, failed, and then announced that he had not really wanted them in the first place because they were sour. Like the fox, many of us decide that what we cannot have we didn’t really want in the first place. This is what is happening with some minority groups in different countries. If people discover that they will never be able to compete with the majority culture because of a lack of skills (or opportunities), they sometimes create identity by claiming they are focusing on different (better) goals.

- The narcissism of the small difference

One way people define themselves is by comparing themselves with the ones in their direct environment. Sometimes, people create differences where there is none to create their own self-definition. This can lead to the “narcissism of the small difference.” This is a concept introduced by Freud. People who are very much alike have a tendency to emphasize the small differences. Mostly, it is a matter of style, musical preference, cooking, and dressing. This, of course, is very superficial and can sometimes even lead to “style surfing”.

Grammar, style, and dialect

A repetitive remark made by participants in my seminars is: I recognize what you are saying about my country. But the people in the North of my country are different compared to the people in the South. The people in the South are different from the people in the East. This is clearly evident for people born and raised in such a country. Belgians are convinced that people from West Flanders are different from the people in East Flanders. The Dutch are convinced that Rotterdammers are different from Amsterdammers. Americans are sure that Americans from the East Coast are different compared to compatriots from the West Coast.

A nice test is to ask the opinion of outsiders. Then the surprising reaction is mostly, “Well, you are a local, so you know best about these differences. But what I see is similar behavior all over the country”.

How to explain this? Comparisons are always dangerous. But the best way is to compare the basic values of culture with the grammar of a language system. Nobody will deny that the basic grammar systems of English, Chinese, Russian and Sanskrit are different. Still, people sharing one basic grammar system can be different in style and dialect. Take the Scottish and the English. They share the same basic grammar system. Still, the Scottish are so different in style and dialect that even the English have difficulty understanding what they say. This is the way to understand most of the regional differences in culture. In almost all countries in the world, people share a homogeneous (majority) culture. But styles and other elements of the superficial layers of the onion can be different.

Imagined and True realities. The problem with MBA programs

If one compares official organizational charts of organizations worldwide, they look very much the same everywhere. The same is true about all other relevant issues for today’s global business players: strategies, HRM systems, including reward techniques, management approaches like MBO, appraisal instruments like 360-degree feedback systems, etc.

Seemingly, the organizations are steered in the same way. In MBA programs everywhere, the same theories are taught, and the general feeling is seemingly that organizational behavior is culture-neutral.

An analysis of these theories learns that most of the handbooks of management, marketing, economy, etc., come from Anglo-Saxon countries: USA, Canada and the UK. The students from MBA programs assume that what they are reading about is just the latest development, the latest description of best practices. After graduating, they try to implement these best practices in organizations in their own countries. If, then, after a time, they discover it’s not successful, they blame the failure on the people involved. Accusing them of being resistant, backward, stubborn, and ignorant. What they don’t realize is that the promoted theories are not wrong but have a value context that fits the motivations of the Anglo-Saxon culture group, but not necessarily the motivations of people in their own country. This is not something that is to blame on the Management Gurus. Frequently, I heard these Gurus’ say: you tell me that this is not possible in your country. Tell me then, please about the theories and research from your culture. Then, most of the time, there is silence. The Non-Anglo-Saxon cultures should do much more in making the realities in their own cultures more explicit. They should be more aware that there is a difference between the “Imagined reality” (assuming, for instance, that what is true or valid in the USA is also true and valid everywhere) is different from “True reality”.

6 Culture, globalization and change

What are the conclusions one can draw from this analysis?

One important element is that in discussions about this subject, it is necessary to define culture and to have a common agreement about the layer of culture being discussed. In most cases, it’s about the superficial layers. Most tourists, if they are interested in culture, will focus on the symbols, heroes, and rituals. In short, the things one can see in museums, during folkloristic festivals, in theme parks, etc. and will not really be confronted with the real values of the culture they are visiting. Even stronger: it’s mostly the locals that will be confronted with the different kinds of expectations and behavior. It is certainly a must for the tourist industry to realize this and to develop skills for their personnel to cope with this diversity. It’s simply a matter of good business to be customer-oriented.

Secondly, It’s a revolutionary finding in marketing that after a certain level of income, culture makes the choices are diverging again, based upon the four value dimensions of Hofstede.

Thirdly, sustainable development can only be achieved if the approach fits the local value structure. One element of this is good governance. This is not a culture-free subject. The issues of good governance in Mexico are different compared to the issues in The USA or Switzerland. The United Nations is aware of this. In a recent paper, they concluded that: “Although economic aspects of development are often taking front stage, such as attracting investment, building infrastructure, etc., not enough attention is given to the need to establish appropriate governance mechanisms and systems to deal with it. Effective and transparent political institutions; an efficient and accountable administration; and mechanisms to foster the participation of citizens in the decision-making process are essential factors in ensuring that the potential benefits of development are maximized and its drawbacks minimized”. This is something that in the “I reality” everybody can agree to. The problem is, however, that in the “T reality”, the issues of what is called good governance are related to the cultural background of the countries involved.

In masculine and individualistic countries like the USA, with short-term thinking and a clear hero culture, the CEOs of companies have to show success to the shareholders constantly. Otherwise, the shareholders go away and invest somewhere else immediately. The danger will always be that there will be that these heroes will be tempted to manipulate the figures. In feminine, low power distance cultures like in Scandinavia, the problem will be that the consensus mentality can lead to an avoidance of free competition and the tendency to make secret agreements between the different so-called competitors.

In high power distance cultures like France and Italy in Europe, all countries in Asia, and all countries in Latin America and Africa, the problem will be that the controlling institutes in the “I reality” are considered to be independent, but in the “T reality” can be subordinate to the power structure.

In collectivist cultures, like in most African countries, the problem can be that the ruling “in groups” will help and involve the people of their own tribe, ethnic group, region, or religious group but will tend to exclude others.

All this leads to one conclusion: also, in the world of (sustainable) development, there should be an awareness that naïve concepts about globalization can actually do harm instead of help. Also, if there is no doubt about the good intentions.

0 Comments