Narrating Change: The Role of Cinema in the Cultural Discourse of the Arab Spring

Amer Bitar

Abstract

The recent history of the Middle East, marked in particular by the Arab Spring, presents a rich tapestry of socio-political transformation. An essential but often overlooked aspect of this period is the role of cinema, both as a reflection of and an influence on this transformation. In this article, I help to fill this gap in the literature by investigating the relationship between the cinematic landscape and national cultures across the Middle East during this pivotal era. Specifically, I analyze The Square (2013), a documentary by Jehane Noujaim on the January 25 Revolution in Egypt to reveal the ways in which cinema transcends the mere reflection of societal dynamics to become deeply embedded in national culture. The film showcases how filmmakers blend local sensibilities with universal themes of revolution, freedom, and identity, thereby highlighting the intricate relationship between cinema and cultural ethos. By analyzing thematic motifs, narrative structures, and cinematic techniques, I show the complex ways in which cinema has alternately embraced and challenged cultural norms and the subtle and overt political messages that such artistic choices communicate. My analysis underscores the power of cinema to shape the perceptions of both domestic and global audiences, bridge cultural gaps, and provide a multifaceted perspective on the geopolitical transformation in the Middle East against the backdrop of deeply rooted traditions and beliefs. As a contribution to film studies, geopolitics, and cultural studies, this research is intended to help policymakers, activists, and scholars appreciate the complex interplay among popular culture, political evolution, and national cultural contexts in the contemporary Middle East.

Keywords: Arab Spring, The Square, Egypt, Middle Eastern cinema, national cultures, national identity, revolutionary themes, contemporary Middle East.

Introduction

In late 2010, a transformative tide began to rise across the Middle East that came to be known as the Arab Spring. These anti-government protests and uprisings, unparalleled in intensity and scope in the region, marked a turning point in contemporary Middle Eastern history. This massive shift was instigated by what appeared to be a localized act—a poignant gesture of defiance by Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor—but, in a kind of domino effect, the impact of this act spread far and wide. From the vibrant medinas of Tunisia to iconic Tahrir Square in Cairo and the strife-torn alleys of Syria, the collective clamor for democratic rights, justice, and civil liberties resonated, giving voice to shared aspirations.

Amid the whirlwind of socio-political change, journalists, political commentators, and scholars tried to account for both the immediate consequences and grand scale of these political upheavals. However, running parallel to these events was a subtler revolution gaining momentum in the shadows. Historically revered for mirroring societal evolution, the Middle Eastern film industry was also at a momentous juncture, and the films of this era bore the onus of reflecting the ongoing societal metamorphosis and shaping the discourse about it.

In this article, I provide a nuanced account of this cinematic realm through a case study of a poignant documentary, The Square (2013), that focuses on key moments as the Arab Spring played out in Egypt, chronicling the efforts of activists as they battled leaders and regimes, risking their lives to build a new society of conscience, where actions and policies of both individuals and institutions are influenced by a strong sense of moral responsibility and ethical consideration. I consider the interplay of art and revolt, the power of narrative as a form of witness, and the dual role of cinema as observer and motive force during pivotal historical moments. My broader argument is that Middle Eastern cinema, in its most potent form, has demonstrated the power to sculpt the cultural narrative and shape the perceptions and dialogues of both domestic and global audiences.

Literature Review

My analysis begins with a review of the role that films have played in cultural and political discourses, with particular attention to the context of revolutionary movements such as the Arab Spring. In the following discussion, I explore the extensive body of research on the dual function of cinema in both reflecting societal issues and driving change to elucidate these dynamics.

Cinema as a Cultural and Political Mirror

The notion of cinema as both a reflection of and commentary on the zeitgeist is deeply rooted in the scholarship of cultural theory. Galtung (1971) provided the basis for this perspective, describing cinema as a mirror that reflects societal conditions in all their intricacy to capture the zeitgeist. This reflective capacity of the cinema is further explored through the lens of racial dynamics by hooks (2014), who demonstrated that film not only portrays vividly the racial tensions in U.S. cities but also serves as a catalyst for introspection and societal critique by members of the audience.

Building on these theories, Miller (2003) introduced the concept of cinema as a “popular mirror,” that is, a medium through which the sociocultural climate is not only depicted but also scrutinized by diverse audiences (Miller, 2003). The work of Shohat and Stam (2014), who argued that film serves as a cultural artifact that both reflects and constructs social reality, shaping and being shaped by the cultural and historical context in which it is embedded, reinforces this notion. Likewise, Kellner (2009) argued that films embody the complex interplay between society and media, reflecting societal struggles and transformations, and Sontag (1977) argued regarding the role of cinema in manifesting and influencing public discourse that films have the inherent ability to express and mold the collective consciousness (Sontag, 1977).

The theoretical frameworks of Althusser (2006) and his concept of ideological state apparatuses (ISAs) also support the notion that cinema is a tool for critical reflection. From this perspective, it is a cultural ISA that functions both as a site for the reproduction of ideology and, paradoxically, a space in which the dominant ideologies can be questioned, and alternative visions can be imagined. In this expanded discourse, scholars’ efforts have yielded a comprehensive understanding of the role of cinema as a cultural and political mirror and a powerful platform for discourse about societal norms and values and for encouraging audiences to engage in critical analysis.

The Influence of Cinema on Cultural Values and Political Perspectives

The capacity of cinema to influence and mold societal values and political ideologies has been extensively examined within the framework of critical theory. Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony is useful for understanding the role of cinema in reinforcing or contesting prevailing ideologies and cultural narratives, serving as an instrument for the dissemination and perpetuation of the dominant culture’s worldview that often reinforces the status quo but also, again, has the power to question it (Gramsci, 1989).

The dialectical relationship between cinema and society is exemplified in the early film The Birth of a Nation by D. W. Griffith (1915), which has been dissected for its role in perpetuating racial stereotypes and influencing attitudes toward race relations in the United States. The contentious legacy of this film underscores the profound impact that cinematic narratives can have on public ideology and the shaping of historical consciousness (Ang, 2023). Wasko (2020) focused on the transformative potential of cinema to argue that it serves as both a medium for entertainment and a critical space for ideological engagement and, once more, the contestation of cultural norms (Wasko, 2020). Similarly, Butler (1990) and hooks (2004) explored the role of films in subverting traditional gender roles and racial identities, thereby contributing to the ongoing discourse of identity politics and social justice. Žižek (2006) likewise analyzed the intersection of cinema with political activism and the role of film as a subversive form of art by critiquing the underlying mechanisms of power structures and ideological struggle. Thus, the consensus view of scholars is that cinema extends into the realm of cultural production and political narrative, not only reflecting but also participating actively in the construction and deconstruction of cultural values and political ideologies.

The Global Impact of Cinema

The worldwide influence of cinema—that is, its power to transcend national boundaries and foster international discourse—is a topic of considerable scholarly interest. Cinema has been described as a universal language capable of conveying complex cultural narratives and fostering a shared sense of humanity across diverse populations. Its global reach has been conceptualized by scholars such as Appadurai (1996), who discussed the role of media, including cinema, in shaping the global cultural flow and the emergence of deterritorialized audiences who engage with films in contexts far removed from their cultural origins.

Nye (2004) has examined the role of Hollywood in particular as a dominant force in global cinema and its influence on global perceptions of culture, politics, and identity, being known particularly for introducing the concept of “soft power,” that is, the ability to influence and attract through culture and ideology rather than coercion. Shohat and Stam (1994) have also critiqued Hollywood narratives, arguing that they frequently perpetuate a Western-centric view of the world and also acknowledging the industry’s power in constructing global myths and fantasies that resonate with international audiences. The works of Said (2003) on Orientalism have been influential in accounting for the power of cinematic depictions to shape and, sometimes, distort Western perceptions of the East, contributing to a discourse that has real-world political implications. Simply put, the influence of cinema on global political consciousness can hardly be overstated.

Conversely, non-Western films such as Akira Kurosawa’s (1950) Rashomon and Satyajit Ray’s (1955) Pather Panchali have challenged Western audiences to engage with alternative narratives and perspectives, thereby promoting a more nuanced understanding of global diversity (Anderson, 1996). The phenomenon of transnational cinema, with filmmakers operating beyond the confines of national industries and identities, is a further manifestation of the global impact of cinema. Iwabuchi (2002) noted that East Asian cinema, in particular, has gained international prominence by challenging the cultural hegemony of Western cinematic traditions and creating new centers of global cultural production. In the era of digital media, the global distribution and consumption of films have been revolutionized, further expanding their reach. Jenkins (2011) is among those who emphasize the technologies that have fueled the rapid global dissemination of films by enabling immediate access to diverse cultural products, thereby facilitating a new form of transnational cultural participation. The global impact of cinema is, naturally, a multifaceted phenomenon with cultural, political, and economic dimensions. As a form of soft power, cinema has the potential to bridge cultural divides, influence political discourse, and shape global identities, so it is an essential consideration for understanding contemporary global dynamics.

Cinema and the Arab Spring

The Arab Spring, the name given to the series of uprisings that dramatically altered the political landscape of the Middle East beginning in 2010, has been a rich subject for documentary filmmakers. The prominent documentaries on this subject both serve as archival footage and create powerful narratives that, as I show here, have contributed to political activism and shaped international perceptions of the events. They include, Bahrain: Shouting in the Dark (2011) by May Ying Welsh, Tahrir 2011: The Good, the Bad, and the Politician (2011) by Tamer Ezzat, Ahmad Abdalla, Ayten Amin, and Amr Salama, 1/2 Revolution (2011) by Omar Shargawi and Karim El Hakim, Zero Silence(2011) by Javeria Rizvi Kabani, In Tahrir Square: 18 Days of Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution (2012), The Square (2013) by Jehane Noujaim, The Uprising (2013) by Peter Snowdon, Return to Homs (2013) by Talal Derki, and We Are The Giant (2014) by Greg Barker. These documentaries have been crucial in communicating the realities of the Arab Spring to a global audience. They have also become a significant part of the cultural discourse and, as such, offer insight into the complex narrative strategies and aesthetic choices that enable documentarians to engage their audiences emotionally and intellectually. The seminal research of Khatib (2008, 2013) has done much to clarify the role of Arab cinema, particularly documentaries, in shaping the political consciousness of both regional and international audiences. My aim in this study is to show the contribution of these films to the understanding of the cultural and political nuances of the Arab Spring by focusing on one of them, The Square (2013).

Methodology

The methodology for this study is based on the genealogy framework, which I approach from a visual perspective. Such a perspective is clearly called for in dissecting the evolution and dissemination of visual and thematic elements in the Arab Spring films. Michel Foucault’s (1977, 1979) concept of genealogy serves here a critical tool for understanding the construction of knowledge within Arab society by exposing and deconstructing the relationships among power, knowledge, and subjectivity. As is well known, Foucault’s genealogical analysis describes the operation of power through the production of truth and knowledge rather than mere coercion or domination. This emphasis on the role of discourse in constituting subjects and objects helps to reveal the ways in which the sciences and institutions contribute to the formation of subject identities (Bitar, 2020). As such, genealogy is a historical-critical method for revealing the contingent nature of knowledge and questioning power relations. This perspective has been influential across disciplines, prompting critical inquiry into the historical and cultural contingencies that influence contemporary understandings and practices.

My operationalization of this methodology involves the following seven steps.

- Compilation of Data. The initial phase involves a comprehensive collection of data. My focus for this project is, as discussed, The Square, a film about the Arab Spring in Egypt. The data collected relate to the January 25 revolution.

- Multimodal Film Analysis. I subject the visual and auditory elements of the film to a meticulous multimodal analysis covering the cinematographic techniques, narrative pacing, and use of space within the frame (mise-en-scène) as well as dialog, music, and diegetic sounds (Bordwell, 2013; Bordwell et al., 1993).

- Close Reading and Coding. The heart of the analysis is a close reading of the film that involves cataloging and coding visual motifs, narrative arcs, and character representations. I devote special attention to recurring images, symbols, and tropes that serve as cultural and political signifiers.

- Intertextual Analysis. This type of analysis serves to reveal the influence of historical and contemporary visual media on a film’s aesthetic through the identification of references, allusions, and stylistic borrowings from other media forms, including television, photography, and internet-based platforms.

- Temporal Mapping. I map the appearance and transformation of visual elements over time, plotting their trajectory as the events of the Arab Spring unfolded to show the influence of the socio-political context on the visual genealogy of The Square.

- I then contextualize each element within the socio-political milieu of the Arab Spring by considering its contributions and challenges to the prevailing narratives of the uprisings and their representation by global media.

- Synthesis and Interpretation. I conclude with a synthesis of the findings in which I discuss the larger historical and cultural implications of the film’s visual genealogy. My focus is on the power of film to shape collective memory, identity, and the ongoing discourse surrounding the Arab Spring.

The implementation of this operational plan guides my analysis of the constituent visual elements of one of the Arab Spring films while drawing attention to their broader significance within the cultural and political landscapes of Egypt and the Arab world. The result is a more nuanced understanding of the visual legacy of the Arab Spring in cinema.

Analysis

1. Compilation of the Data

My analysis, then, focuses on The Square (2013), a documentary film directed by Jehane Noujaim that presents an unvarnished and deeply engaging picture of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, also known as the January 25 Revolution. This grounded account captures the fervor, chaos, and complexities of the events as they unfolded in Tahrir Square in Cairo. This compelling chronicle of a pivotal historical epoch vividly encapsulates the trials and hopes of ordinary Egyptians pursuing transformative change. Noujaim adopts a raw, verité style, immersing viewers in the revolution to convey both the intensity and the uncertainty of the scene. She views the uprising through the eyes of various activists who played central roles in it. The interlacing of these personal stories with the social and political developments highlights the diverse motivations and backgrounds of the individuals involved as well as the universal themes of justice, freedom, and political transformation. The film has garnered extensive praise for its intimate, powerful narrative style, earning an Academy Award nomination and securing three Emmy Awards in 2014. Its artistic excellence and insightful contribution to the discourse on the complexities of contemporary social and political movements make The Square an invaluable resource for academic discussions encompassing documentary filmmaking, Middle Eastern politics, and the dynamics of modern revolutions.

2. Multimodal Film Analysis

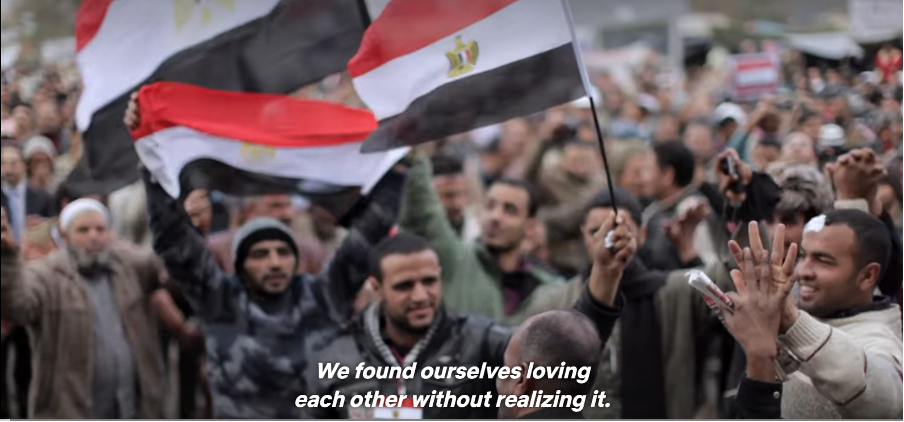

In my multimodal film analysis of the documentary, I attribute its powerful impact to both its content and its meticulous integration of visual and auditory elements. The cinematography is characterized by the dynamic use of handheld cameras to capture the immediacy and chaos of the Egyptian Revolution (Figure 1). This raw filming approach creates the aforementioned immersive experience, placing the audience in the center of the tumultuous events in Tahrir Square. The narrative pacing is equally significant, shifting between rapid sequences of protest and more reflective moments to provide a nuanced depiction of the emotional landscape of the revolution (Figure 2). The mise-en-scène plays a crucial role, utilizing the space within the frame to convey the enormity of the crowds and the scale of the uprising while, again, also including intimate moments that humanize the struggle. Auditory components also help to create and propel the film’s narrative, particularly the dialog among the activists that provides authentic insights into their thoughts, motivations, and language in expressions such as “breaking the fear”, “battling injustice”, “corruption”, “poverty”, and ignorance,” “no hope, no future,” and “enough of walking cautiously on the side.” The ambient sounds of chants, crowds, and conflict immerse viewers in the atmosphere of the revolution as one of the main characters emerges, Ramy Essam, who sings the timely song “We Are All One Hand” (Figure 3). The selective use of music further accentuates key emotional and thematic points, underpinning the film’s narrative arc. Overall, my multimodal analysis reveals how The Square employs a synergistic combination of visual and auditory storytelling techniques to create a compelling and authentic depiction of the historic events of the January 25 Revolution.

Figure 1 Still from The Square showing the chaos.

Figure 2 Still from The Square showing the protesters’ emotions.

Figure 3 Still from The Square showing singer Ramy Essam.

3. Close Reading and Coding

Through a close reading of the film, I meticulously catalog and code the film’s visual motifs, narrative arcs, and character representations to uncover deeper meanings and cultural-political contexts. A recurrent visual motif is panoramic shots of Tahrir Square showing it as both the epicenter of the revolution and a microcosm of the larger Egyptian struggle (Figure 4). These shots often juxtapose the vastness of the crowd with the solitary figures of activists, contrasting the collective nature of the movement with individual experiences. The non-linear narrative arc reflects the unpredictable and tumultuous nature of the events as they unfolded and represents a challenge to traditional storytelling methods. The representations of activists such as Ahmed Hassan and Khalid Abdalla show them as political figures and complex individuals, with each character embodying a distinct facet of the revolutionary spirit (Figure 5). Their personal journeys and evolving perspectives serve to humanize the uprising. Additionally, the film employs recurring symbols such as graffiti, flags, and makeshift medical stations as signifiers of resistance, national identity, and grassroots mobilization. More than just visual aesthetics, these symbols are replete with cultural and political significance and, as such, offer insight into the societal undercurrents that fueled the revolution. My close reading shows The Square to be a rich tapestry of visual storytelling in which every motif and character deepens the audience’s understanding of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution.

Figure 4 Still from The Square showing the titular location.

Figure 5 Still from The Square showing the focus on individuals.

4. Intertextual Analysis

My intertextual analysis of the film’s aesthetic reveals the deep influence of both historical and contemporary visual media. Its stylistic lineage traces to earlier forms of visual journalism and documentary filmmaking, particularly in the raw, verité approach, which echoes the directness of wartime reportage. The handheld camera work and close-up shots show stylistic borrowing from television news coverage and contribute to the immediacy and intensity of the narrative. Other elements of photojournalism in the film include its composition and framing of scenes, which often parallel powerful still images that have historically captured the public imagination during major political events (Figure 6). Notably, the film’s aesthetic is also influenced by internet-based platforms in its use of user-generated content, such as mobile phone footage taken by protesters, which acknowledges the growing significance of social media for contemporary socio-political movements. The integration of the various media forms enhances the authenticity of the narrative and reflects a broader trend in documentary filmmaking toward an emphasis on diverse and immediate sources of visual information. The resulting rich, layered narrative resonates with a wide range of audiences and pays homage to the multifaceted nature of visual storytelling needed to capture and convey the underlying political and social realities.

Figure 6 Still from The Square showing the photojournalistic style.

5. Temporal Mapping

The film’s visual genealogy then, evolves in tandem with the socio-political landscape, mirroring the tumultuous progression of events. Thus, the early scenes are marked by a hopeful, vibrant aesthetic that captures the initial euphoria and unity among the protestors in Tahrir Square. These scenes are rich in color and characterized by wide shots of massive, peaceful crowds that show the collective aspiration for change (Figure 7). As the narrative advances, paralleling the escalation of the revolution, the visual tone shifts dramatically. Thus, the color palette becomes more muted, reflecting the growing uncertainty and despair. The camera angles also become tighter, focusing on the strained faces of individuals, personalizing the political struggle (Figure 8). The scenes of conflict and violence are captured with a visceral intensity that differs sharply from the earlier images of peaceful protest. This shift in visual style is not merely aesthetic but also reflects the descent of the revolution into chaos, with the raw, unpolished footage in later parts of the film underscoring the harsh realities faced by the protestors and, again, contrasting with the initial idealism portrayed onscreen. Through such temporal mapping, the film combines documentation of the events of the Arab Spring with a deep analysis of the evolving socio-political context. Its visual narrative offers a compelling, multi-layered glimpse of a nation undergoing profound transformation.

Figure 7 Still from The Square showing the early euphoria of the crowds.

Figure 8 Still from later scene in The Square showing the despair of individuals.

6. Contextualization

In the film’s profound contextualization of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, each element is meticulously woven into the socio-political fabric of the era. The narrative centered around Tahrir Square provides a ground-level view of the personal stories of activists and the larger political tumult. This approach humanizes the events and challenges the monolithic, often distant portrayal of the Arab Spring in global media. By incorporating diverse perspectives that include a young revolutionary and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, the film avoids simplistic narratives in favor of the complexity and internal contradictions that characterized the movement as it evolved. Likewise, the raw, unfiltered visual language challenges conventional media representations and offers an immersive experience of the fervor, chaos, and hope of the times. This contribution to the discourse on the Arab Spring is significant in terms of documenting a pivotal moment in history and prompting a reevaluation of the perception and representation of such uprisings worldwide. In these respects, The Square dramatizes the power of grassroots activism and the enduring quest for democracy without downplaying the challenges and setbacks inherent in such transformative movements.

7. Synthesis and Interpretation

The film serves as a multifaceted lens through which the Egyptian Revolution and, by extension, the Arab Spring can be understood in all its complexity. Director Jehane Noujaim’s methodology, combining the verité style with a focus on personal narratives, places the audience in the midst of the events. My analysis shows the film to be a vibrant tapestry of human experiences reflecting the diverse motivations and backgrounds of the participants in the revolution. The integration of visual and auditory elements creates a deeply immersive narrative, and my close reading and coding of the film’s motifs and character representations serve to uncover its rich layers of cultural-political contexts.

In its temporal mapping, The Square brilliantly charts the evolution of the revolution, capturing the transformation of the initial optimism into a complex, often grim reality. This visual and narrative shift reflects the dynamism of the socio-political landscape, thus offering powerful insight into the nature of the revolution. My intertextual analysis further enriches this understanding by placing the documentary within the broader tradition of visual journalism and documentary filmmaking and accounting for its innovative use of contemporary, user-generated content. The contextualization of the socio-political milieu of the Arab Spring is, perhaps, the film’s most significant achievement, in that it not only provides an account of the events but also invites a reevaluation of how such uprisings are perceived and represented globally, thereby challenging monolithic narratives with a nuanced view of a movement marked by internal contradictions and diverse perspectives. The film thus documents the history of the Arab Spring and offers a critical commentary on the nature of social and political transformations in the modern era. Its insightful portrayal of the Egyptian Revolution transcends the boundaries of documentary filmmaking while contributing significantly to the academic discourse in fields ranging from Middle Eastern politics to media studies and revolution dynamics. In sum, The Square is a seminal work of documentary cinema that provides a rich, multi-dimensional perspective on one of the pivotal moments in the 21st century thus far.

Discussion

The Square chronicles the Egyptian Revolution from 2011 to 2013 with a focus on the events in and around Tahrir Square in Cairo, the epicenter of the uprising in the country. It unfolds as a real-time chronicle, capturing the fervor and hope of the revolutionaries and the challenges that they faced. The narrative traces the initial surge of collective optimism following the ouster of President Hosni Mubarak[1] through the interim military rule to the subsequent election and divisive rule of Mohamed Morsi.[2] The plot develops in a series of dramatic turns as peaceful demonstrations give way to violent clashes, political alliances form and dissolve, and the quest for democracy is met with brutal resistance by the authorities. The narrative is anchored in the experiences of the key characters, who represent various facets of the uprising. They include Ahmed Hassan, a passionate young revolutionary whose idealism and resilience represent the spirit of the broader movement, Magdy Ashour, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood whose conflicted loyalties reflect the complexity of the political landscape, Khalid Abdalla, an actor and activist who becomes a prominent voice of the revolution bridging the gap between the local struggle and international audiences, and Ragia Omran, a human rights lawyer and activist whose commitment to justice and reform provides a crucial perspective on the legal and human rights dimensions of the conflict. Through these personal stories, the documentary vividly captures the passion of the early protests, the subsequent political turmoil following the military’s rise to power, and the constant struggle for democratic reform. The poignant portrayal of hope and despair, of unity and division, captures the essence of a revolution that reshaped Egypt and had far-reaching implications for the entire region in a powerful testament to the resilience of the human spirit in the face of overwhelming odds and the unyielding pursuit of freedom and justice.

The Square is a significant documentary owing to its aesthetic innovation and insightful exploration of a critical historical event. Aesthetically, the film breaks new ground with its verité style, in particular, the use of handheld cameras. The resulting visceral experience places viewers in the center of the uprising, an approach that distinguishes this film from more traditional documentaries. The dynamic use of cinematography combined with the careful pacing and strategic use of mise-en-scène create an engaging and evocative visual narrative. The film is of immense importance for its presentation of the complexities of the Arab Spring, transcending mere reporting to offer a nuanced view of the revolution by interweaving the activists’ personal stories into the broader socio-political commentary. By both humanizing the momentous events and providing a multi-dimensional perspective on them, it challenges the often oversimplified narratives presented in global media and also exemplifies the power of documentary cinema to convey complex political and social realities with depth, nuance, and emotion.

The aesthetic framework, then, is no mere storytelling tool but, rather, an example of art as an instrument of freedom and resistance. The immediacy and intensity of the cinéma vérité style draw the audience into the protest (Nichols, 2017) and are crucial for conveying the reality of the uprising and the unfiltered voices of the people. The examples of artistic expression that the film captures, such as graffiti and street performances, likewise serve as potent symbols of resistance, showing the capacity of art in public spaces, particularly during times of socio-political unrest, to transcend traditional forms of communication by embodying both dissent and hope. This spontaneous popular art both adorns and drives the narrative, serving as a channel for the expression of grievances and aspirations as the public spaces of Tahrir Square transformed into arenas of political discourse. Moreover, the juxtaposition of artistic expression with acts of brutality by the regime underscores the role of art as a kind of non-violent weapon. Thus, in The Square, the portrayal of art in various forms testifies to the resilience and creativity of the revolutionaries and to the role of art, in times of social and political oppression, as a beacon of hope and a medium for change (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9 Still from The Square showing an artistic representation of the protests.

Figure 10 Still from The Square showing a street performance.

The use of visual genealogy to analyze documentary films allows for a rich and in-depth exploration of the substance and the stylistic elements and is especially appropriate for a work as intricate and multi-faceted as The Square. By tracing the development and interaction of the various visual components within the film, I reveal its narrative and thematic essence. My application of visual genealogy helps to make sense of the cinematographic choices, including the use of handheld cameras and close-up shots, in narrating the events as the January 25 Revolution evolved rapidly. I show how the visual style contributes to the story and communicates a sense of the emotional and political nuances of the historical backdrop. My use of visual genealogy shows in detail how Noujaim’s documentary transcends simple reportage to function as a compelling medium for engagement and empathy (Rose, 2012). Thus, the combined effect of the aesthetic choices that went into The Square is a vivid depiction of the shift from optimism to despair, solidarity to fragmentation, and disorder to perseverance as the revolution evolved. My analysis based on visual genealogy deepens the appreciation of the documentary as both a work of art and a historical narrative and its significance as a case study for film studies and visual cultural analyses.

My analysis reveals three key themes underpinning the narrative. First, the film addresses the concept of national identity, in this case, a unified Egyptian identity that transcends sectarian divisions. Thus, in the early stages of the revolution, Muslims and Christians are shown chanting slogans such as “We are all one hand, and our demands are one” and calling for unity, emphasizing the need to transcend political differences in the face of a common goal. In poignant moments, the protesters voice concerns about divisive tactics and a keen awareness of the potential for sectarian strife. Second, the emphasis is on the peaceful nature of the protesters’ commitment to non-violence in asserting their demands. Third, the film challenges patriarchal hegemony by showing that women were not mere participants but central figures in the movement, thus offering a powerful counter-narrative to the traditional depictions of the role of women in revolutions that underscores the inclusive nature of the Egyptian uprising (Figure 11). The prominence of these themes contributes to the nuanced picture of the revolution and evinces the skill of the director Noujaim in capturing the complexity of this historical event.

Figure 11 Still from The Square showing a female protester.

Conclusions

I have argued that the 2013 documentary The Square well represents the profound impact that cinema can have in terms of shaping the cultural discourse about significant historical events, in this case, the Arab Spring in Egypt. Jehane Noujaim’s vivid portrayal of the January 25 Revolution extends the boundaries of documentary filmmaking by using verité aesthetics to tell a deeply human story. The film captures the essence of one nation’s struggle for democracy and also offers broader reflections on freedom, resistance, and the power of collective action. Through the use of visual genealogy as an analytical framework, I have revealed some of the intricacies of the visual and auditory elements that serve to respond to and dramatize the socio-political upheavals of the time. As a cultural artifact, The Square captures the tumultuous spirit of the Arab Spring, presenting a broad cross-section of the diverse voices and experiences that characterized the movement. The raw style conveys the immediacy of the protests and the protesters’ complex emotional landscape, and the unique perspective shows the Arab Spring to have been a cultural and social turning point as well as a political one.

By foregrounding the intersection of individual stories with the collective struggle, The Square dramatizes the blending of personal aspirations with the quest for democracy and freedom. In these ways, it offers a nuanced portrayal of the events and their implications that challenges monolithic narratives about the Arab Spring. Not surprisingly, then, it has played a crucial role in shaping the cultural discourse about the wave of change that swept through the Arab world in the early 2010s, and it is likely to influence future generations’ understanding of this key historical moment. By integrating theories from cultural and film studies, I have shown that The Square both mirrored and molded the zeitgeist so as to influence the perceptions and discussion of the Arab Spring worldwide. As both part of the historical record and a testament to the transformative potential of cinema, this documentary has shaped the cultural narrative and political consciousness, helping to catalyze social change by echoing the sentiments and aspirations of a people in revolution. It stands to serve as a beacon for future generations seeking to understand the complexities of their past.

Notes:

[1] Muhammad Hosni Mubarak was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served from 1981 to 2011 as the fourth president of Egypt.

[2] Mohamed Morsi was an Egyptian politician, engineer, professor and member of the Muslim Brotherhood who served from 2012 to 2013 as the fifth president of Egypt.

References

Althusser, L. (2006). Lenin and philosophy and other essays. Aakar Books.

Anderson, J. (1996). The reality of illusion: An ecological approach to cognitive film theory. SIU Press.

Ang, D. (2023). The birth of a nation: Media and racial hate. American Economic Review113(6), 1424-1460.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization (Vol. 1). University of Minnesota Press.

Bitar, A. (2020). Bedouin visual leadership in the Middle East: The power of aesthetics and practical implications. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bordwell, D. (2013). Narration in the fiction film. Routledge.

Bordwell, D., Thompson, K., & Smith, J. (1993). Film art: An introduction (Vol. 7). McGraw-Hill.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of indentity. Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheidan, Trans.). Penguin Books.

Foucault, M. (1979). The history of sexuality, volume I : An introduction (R. Hurley, Trans). Pantheon Books.

Galtung, J. (1971). A structural theory of imperialism. Journal of Peace Research, 6, 167–191.

Gramsci, A. (1989). Selections from the Prison Notebooks (Q. Hoare & G. N. Smith, Eds.). International Publishers.

hooks, b. (2004). The will to change: Men, masculinity, and love. Simon & Schuster.

hooks, b. (2014). Black looks: Race and representation. South End Books.

Iwabuchi, K. (2002). Recentering globalization: Popular culture and Japanese transnationalism. Duke University Press.

Jenkins, H. (2011). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales, 20, 129–133.

Kellner, D. M. (2009). Cinema wars: Hollywood film and politics in the Bush-Cheney era. John Wiley & Sons.

Khatib, L. (2008). Lebanese cinema: Imagining the civil war and beyond. I.B. Tauris.

Miller, T. (2003). Television: Critical concepts in media and cultural studies (Vol. 1). Taylor & Francis.

Nichols, B. (2017). Introduction to documentary. Indiana University Press.

Nye, J. S. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. Public Affairs.

Rose, G. (2012). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (3rd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

Said, E. W. (2003). Orientalism. Penguin Books.

Shohat, E., & Stam, R. (2014). Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media. Routledge.

Sontag, S. (1977). On photography. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Wasko, J. (2020). Understanding Disney: The manufacture of fantasy. John Wiley & Sons.

Zizek, S. (2019). The sublime object of ideology. Verso Books.

0 Comments