Paulo Finuras, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Organisational Behavior

ISG – Lisbon Business & Economics School

E-mail: paulo.finuras@isg.pt

Many behavioural scientists believe that the phenomenon of identity can be analysed from two perspectives. On the one hand, from an individual point of view, identity serves to characterize and distinguish each person, having natural and socially constructed elements and that its main characteristics are continuity and contrast, both functioning as symbolic signs. On the other hand, as an evolutionary species, humans have always been dependent on groups for survival, and therefore, it is natural that identity has so much to do with the individual, his relationships, decisions, life trajectory and feelings attached to his experience and how he sees himself and thinks that others see him. With regard to social identity, it is proposed that it evolved from the tribal social instinct and the relationships between individuals, based on similarities and, therefore, becoming the main element that promotes social trust, in addition to affiliation. In this article, we reflect on the isomorphism of the identity concept in its various applications in general and its consequences in particular for the construction of trust and social navigation in the context of human evolution.

Keywords: Collective action, Trust, Coalition, Identification, Tribal Instinct, Similarity

-

What is identity: the importance of limiting an isomorphic concept

Let’s start with the principle. When we talk about identity what are we talking about? This is a recurring problem in behavioural sciences and perhaps the first to consider, that is, to delineate the concept and its meaning because, as with many other concepts (such as culture and personality), one thing is the form (the word), and another is the meaning (the sense).

In terms of origin, identity can mean several things. Right from the start, the “fact of being who or what a person or thing is; a similarity or close affinity; the distinct character or personality of an individual; individuality or the relationship established by psychological rapport and, the quality of what is identical, parity or absolute equality or set of characteristics (whether physical and / or psychological) essential and distinctive of someone, a social group or something.”[1]

As we can see, identity has multiple meanings, referring to categories, social roles, or even, simply, to information about us and others.

Identities, therefore, emerge from a need to distinguish between the inner self and the world around us, just as they emerge from the inner “we” of groups in relation to other groups in the outside world. In either case, it recognizes the existence of “me” or “we”. We conclude that, in evolutionary terms, identity matters and identities themselves are as old as the so-called behaviourally modern human beings.[2]

In summary, identity is always something that characterizes and distinguishes one thing from another. Bearing this in mind, we will discuss and reflect on its function, origin, construction mechanism, development and describe some of the consequences, both from the individual identity and evolutionary perspectives as a group´s social phenomenon associated with the resolution of humans´ adaptive challenges (Giddens, 1991Tinbergen, 2005)[3].

-

Foundations of identity: function, origin, mechanism and development.

It is clear that identity serves a purpose, which is to provide uniqueness that distinguishes it from other identities, characterizes it, and gives it continuity, while also providing contrast to other things or people. As a result, identity ensures differentiation.

Identity also serves as a signal to acknowledge one’s existence, as an individual or as a group, and is thus a form of recognition in and of itself. When considering its evolutionary origins, we must first determine what kind of identity we are referring to, as it relates to individuals and groups, structures, institutions, countries, believes and ideas.

What´s common about all of the above is a characterization and differentiation method. Identity is constructed through the attraction and convergence of similar elements that, after being organised and stabilized, provide a characterization of and for itself, and others. Its evolutionary function is natural from the perspective of coalitional psychology, which has always defined and guided human survival and is embedded in our minds. Coalitional psychology[4] combines our ancestors’ intuitive and adaptive mechanisms as a set of symbolic capabilities that allow people to create and signal alliances and solidarities, as well as mark their membership, commitment, and loyalty. This natural and intuitive mechanism may have become more important as groups grew in size, acting as a foundation for both internal cohesion and competition for resources and dominance.

-

From natural to social identity

Identity is part of our need for recognition (Fukuyama, 2018) and the coalitional psychology that characterizes us (Boyer, 2018). It incorporates how people perceive and identify themselves and compare to other individuals or groups. Being by name, profession, ethnic or national origin, stage of life, or any other categorizing element, the causes and origin of identity lie in the need for recognition and differentiation between individuals or within and in relation to groups, as well as groups among themselves, guiding and mobilizing beliefs and convictions, creating alliances, and so on.

Furthermore, it is well known that one of the fundamental features of the dynamics of human relationships relates to the concept of an internal and external group. From a socio-psychological standpoint, these dynamics imply a sense of belonging that is fundamental to the human experience[5]. Indeed, establishing boundaries between internal and external groups has always been an integral part of many conflicts throughout our collective history, and it is still at the heart of many human and collective issues today.

-

How and why identities are formed?

Why is it important to have an identity? What are the functions of this fundamentally symbolic process, given that social identification entails the formation of a self-representation as a member of a group or collective?

The main explanation is that humans have evolved to experience their own representation in symbolic terms because it allows them to convey information about who they are and to manage their own behaviours taking into account the expectations and intentions of those with whom they interact, as well as the effects of their actions on others.

The main idea here is that self-awareness, in symbolic terms, helps individuals and groups to predict how their behaviour and actions will affect how others judge them and, ultimately, how they will be accepted into their inner circle of trust. Essentially, identity facilitates social navigation.

The construction of identity often involves relatively high costs, such as passages and submission to rituals of bonding or initiation, the display of ornaments on the body, and other bodily alterations that only serve to signal loyalty and belonging.

This suggests that a kind of “honest costing signalling” (Zahavi, 1997) could be at play, with the expectation that the costs of belonging to a group will be offset by its advantages and as information of one´s membership to outsiders.

In other words, identities are also signalling because a sign, in evolutionary terms, is any trait or behaviour that serves to communicate or carry information. Therefore, the distinctive traits or behaviours and signs of belonging will have evolved to modify the behaviour of the recipient in benefit of the sender.

Since social acceptance has always been critical for individual survival, it is natural that the idea that each person has of himself in public terms, as well as the identity of belonging that each one signals, is rewarding to them, despite the costs involved. This is because individuals cannot survive without cooperation, which is facilitated when an individual identifies with a group, signals his/her intentions, commitment, and loyalty. Thus, it is natural and adaptive for us to have developed psychological mechanisms of adherence, belonging, and connection to groups, which are signalled by the identity of both the individuals and the groups to which they belong.

Therefore, whether through nature or through social construction, identities are everywhere. They emerge from nature itself with hierarchies and bio classes, such as gender, ages, life stages or other biological markers. Subsequently, they are complemented by all experiences and social paths taken during the life of individuals through various assumed identities, which is why they are socially and culturally constructed and a result of coalitional group psychology. For instance, the mother tongue serves as an initial platform for social and cultural identification, and as the foundation for the tribal social instinct that will accompany individuals throughout their lives (Van Vugt & Park, 2010).

It is suggested, therefore, that social identity, in a broad sense, relates to the need for signalling group affiliation and coalitional orientation in terms of cooperative intentions. In other words, individuals’ social identity is formed (and continue to be formed) as a sort of a summary presentation of the different loyalties that individuals acquire and exhibit, emphasizing the need for recognition.

Thus, it seems acceptable that social identity is supported by adaptive psychological mechanisms since coalitional psychology is part of human beings.

Once we acquire a code to connect and understand others, collective practices and preferences (i.e., values) begin. This happens through contacts, and life experiences with others, whether they are real entities or simply, ideas.

-

What is the purpose of Identity?

The short answer is this: identity is meaningful, or, as I mentioned earlier, it recognizes the sense of existence of both the “I” and the “we”, hence its immediate value. Identity enables us to define and compare ourselves to others, as well as to navigate the dynamics of tribal or group coalitions of all shapes and sizes. Identity represents belongings and defines boundaries.

Whether with a group, a club, a company, a profession, a neighborhood, a village, a city, or a country, identity means something to people and enables us to acquire a structure, facilitate our decisions, actions, and social navigation, thereby gaining the benefits of belonging to various groups, including the solidarity of others. As a result, and in some ways, identities are both inclusive and exclusive. According to sociologist Émile Durkheim[6], solidarity in ancestral tribal societies stemmed from similarity and awareness of ethnic group membership, and it appears that in most cases, individuals feel morally obligated to those with whom they share identity. Still other authors, like Chambers[7] (1995) have suggested that the underlying causes of sociolinguistic differences result from the human instinct to establish and maintain a social identity. And, in fact, it turns out that the use of language, for example, goes far beyond the simple need for efficient communication or exchange of information, as individuals also use their linguistic codes to create and maintain social identities and to define borders, without forgetting that the very morality of exchanges, reciprocity and solidarity, is also related to the social identities of the individuals and groups to which they belong.

From an evolutionary point of view, it becomes clear that social identity served and continues to serve as a social marker because it facilitates cooperation and the benefits of being connected to groups.

-

Identity and similarity: the foundations of trust

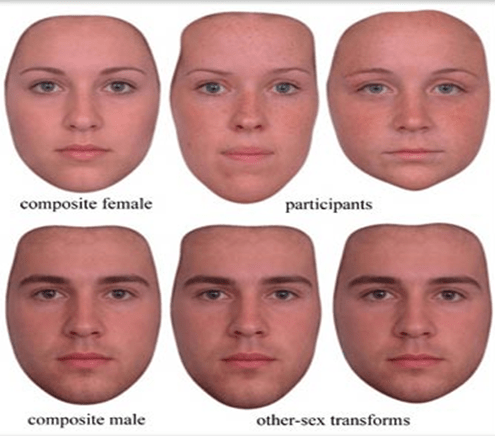

For some time now, research has shown that identity is strongly marked by similarity. For example, Robert Putnam[8], quoted by Boyer (p. 64, Op. Cit.), suggested that an increase in diversity is sometimes correlated with a decrease in social trust (that is, the idea that others in general are, or not, trustworthy). The same author also mentions a study carried out in Denmark according to which “social trust tends to decrease due to the number of foreigners who can be found” (Op. Cit. P.65). While other studies on social trust also show that Scandinavians, like the Chinese, have higher levels of social trust[9]. A researcher[10] has developed a technique that allows to create a computer image of another person that can be transformed to look more and more (or less and less) as the face of the participants involved in the study. She found that the greater the similarity, the more the participant trusted the person in the image (See Image 1).

Additional research has revealed that we tend to trust and like people who are members of our social group or circle of trust more than we like or trust strangers. Indeed, this group effect tend to be so strong that even random allocation of individuals to small groups is sufficient to foster feelings of solidarity, belonging, identity, and trust among group members.[11]

Image 1

The greater the similarity, the more the participant trusted the person in the image.

Source: DeBruine, Lisa. (2005). Trustworthy but not lust-worthy: Context-specific effects of facial resemblance. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 272: 919-922. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3003 (University of Glasgow); Boyer, P. (2018). Mind Make Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

As early as 1963, William Hamilton (known for his famous rule)[12] suggested that any organism tends to help another as long as there is a minimum of genetic proximity or identity between them. The closer they are, the more likely they will behave altruistically. In other words, each act of cooperation and/or trust would be motivated by a kind of fundamental identity or “genetic egoism” with the sole purpose of preserving (and reproducing) a particular genome. For example, from an evolutionary perspective, we can assert that trust has evolved and will continue to evolve in circumstances where natural selection favours it, namely, when those involved identify and cooperate with one another, and thus produce a mutually beneficial trust relationship. The creator of this equation dubbed it “Hamilton’s Rule,”[13] and it is defined by the formula: β b > c

According to this formula, c) represents the cost paid by the “trustworthy” to produce a benefit b) for the “trustworthy”. The symbol β translates the statistical relationship called “regression coefficient”. Essentially, it measures the probability that trust could endure if those involved (those who trust and those who are trusted) continue to produce it as a mutually beneficial “asset.” The more this interaction is repeated under these terms, the more trust can be sustained, because both parties receive more benefits than losses. In conclusion, identity and identification are worthy.

It is likely that this tendency to trust people who resemble us may be rooted in the possibility that such people may be, or have, an identity related to ours and may also mean that ethnic homogeneity is an important variable in the recognition of identity and the formation of social trust, that is, the belief that most people are trustworthy.

Essentially, this is because the identity that produces similarity, generates attraction and attraction provides emotional comfort. From here it is easier to establish social trust between people or to assume that others are trustworthy (Finuras, 2017).

This “trust based on similarity or identity” basically means that individuals tend to trust more readily and quickly, individuals they perceive as their peers, a phenomenon that some authors (Zucker, 1986 and Kipnis, 1996) called “trust based on characteristics’. This type of trust, which is highly prevalent among citizens of the same country, is based on norms of obligation and cooperation that are rooted in social and ethnic similarities, which may reflect physical similarities or other factors such as family background, social status, ethnic origin, or nationality (see Tables 1 and 2). Additional research indicates that the overwhelming majority of a country’s citizens trust their fellow citizens first. And why is that? Because it appears that trust is more difficult to build in situations of diversity, as people are uncertain about the cultural norms of others and, consequently, about their intentions (Inglehart, 1991, Fukuyama, 1995, Kipnis, 1996).

Knowledge about other people’s cultures can be limited and based on stereotypes, prejudices, or partial images, which can lead to uncertainty about what to expect. People tend to divide or categorize others in order to simplify relationships, resulting in stereotypes that can be biased or distorted and, ultimately, transformed into prejudice.

These identity stereotypes are thus the way people think about categories: those with whom they share a social and societal bond and those who are outside that group (Tajfel, 1981, Giddens, 1994). Once others are categorized, individuals tend to create biased assumptions based on the group to which they belong, their values, preferences, behaviours and reliability (Messick and Allison, 1990). In light of this, people are more likely to be suspicious of out-group than in-group members, and to stereotype them more quickly and negatively, whether they are individuals, groups, or, on a larger scale, categories such as ethnicity or nationality, and these biased attributions about the abilities, intentions, and actions of out-group members can fuel feelings of distrust and exclusion. Moreover, when people identify themselves as belonging to the same group, their behaviour tends to be manifestly warmer among themselves and more suspicious and distant towards those who belong to or are identified as members of other groups.

We can even assert that there is a universal human tendency to attribute the motivations for out-group members’ behaviour to fundamental attitudes and values, whereas for in-group members, we tend to consider contextual factors that may influence their behaviour (Messick and Allison, 1990), implying that it is easier to commit the so-called “fundamental attribution error” (FAE) to those with whom we associate (Messick and Allison, 1990).[14]

Typically, individuals are more likely to seek information that is consistent with the attitudes and beliefs of the group or groups with which they identify and tend to disregard the information that refutes them.[15] However, group prejudices can be destructive, not only because they make people look at the members of the out-group with suspicion, but because they can also lead to increased confidence in the members of the in-group. In other words, people develop a form of “prejudiced tolerance” toward members of their group and tend to give other members of the same group the benefit of the doubt when confronted with information that would otherwise be interpreted as an indication of the other’s lack of reliability (Brewer, 1995, 1996).

As in another publication, I have had the opportunity to mention (Finuras, 2013), tables 1 and 2 show the results in the scope of a study carried out by Gerry Mackie (2006) based on another European study on trust between several nationalities. As it shows, the overwhelming majority of people surveyed (90%) indicate that they trust more, and foremost, individuals of their nationality, although it is not said in what terms and in what.

Table 1

Degree of Trust between Nationalities in the European Union for 15 Countries in 2006[16]

Source: Gerry Mackie (Op. Cit.)

Assessments of trust based on confidence or in groups can have very real consequences for organizational and institutional functioning. One study[17] found that superiors lacked confidence in subordinates who had lower levels of status at work or who were predominantly members of minority groups, and thus lacked the willingness to involve them in the decision-making process.

Table 2

Order of preference in terms of the degree of trust between 15 nationalities in the EU

(2006)

Source: Author compilation based on Gerry Mackie (Op. Cit.)

In another study[18], it was also suggested that when teachers in an urban neighbourhood made judgments about the trust they had in students and their parents, socioeconomic status was a much stronger dividing line than were, for example, differences in ethnic origin. Apparently, people who perceive themselves to be different, require more time to see themselves as part of “the collective.” Similarity creates “common ground” that facilitates potential trust. As I have previously stated (Finuras, 2014), this perspective assumes that interactions between individuals are an important factor in promoting trust, as people trust those with whom they interact the most.

Another example is a 2016 study that asked people in six countries, “Who did they most trust in their workplace?” It has been proven that the greatest trust is given to those who are closest to us (See Graph 1).

Credits: EY, 2016

It’s also worth noting that trust appears to be higher in “more open” societies which are able to create a structure that recognizes and rewards cooperative behaviour and encourages fluid interaction between people in order to manage predictability. In turn, in “closer”[19] societies, interpersonal trust tends to develop less, and different levels of high “trust” may coexist in the same context.

As mentioned previously, theories and studies carried out so far, suggest that trust is influenced by the psychological process that allows someone to be recognized as similar or closest to him or her. In these cases, variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, family status and education (among others that produce similarity), play an important role in the development of relationships of trust within the framework of a common identity.

We can infer that the greater the number of affinities or social similarities, the more people will assume that there is an identifiable “common ground,” and, therefore, trust is virtually easier to build or produce.

In general terms, trust seems to be influenced by similarities or identities that bring people together, or by differences, that generate distance or bring people apart, and these similarities and differences can, and are, evaluated from different perspectives and with different individual and collective heuristics. (Finuras, 2020).

In fact, the need for conformity is also stimulated by identity and identification with groups we belong to. When significant event occurs and needs to be explained, individuals tend to reason not so much in search of the truth but in search of a justification for themselves and others that fits the preferred conclusion, a phenomenon known as “motivated moral reason.”[20]

Depending on the identity and emotional strength of each individual, it is natural for emotional or intuitive responses to generate preferences that lead to the processing of subsequent information based on the motivation to reach the desired conclusion. Perhaps this explains the riots that erupted at the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. Individuals wanted to believe that the elections were rigged and did not want to accept, or distrusted, claims that contradicted them, even if the former had no basis or evidence. Essentially, motivated by group identification, individuals want and seek the conclusions they already believe in, while denying or ignoring those that contradict their reasoning. Perhaps as a result of all of this, it is not surprising that a critical factor in increasing trust is a society´s ability to minimize differences between social groups, by promoting equal opportunities[21] and strengthening various forms of cooperation.

According to some researchers (Knack and Zack, 2001; Zack, Kurzban, & Matzner, 2004, Zack, 2010), interpersonal trust is greater in societies and organizations that are more just, ethnically, socially, and economically homogeneous, and where social and legal mechanisms to punish or limit opportunism are more developed and consistent.

In conclusion, a final reflection on a concept that has been used to define social identities and is, in my view, both useless and dangerous. I’m referring to the notion of race. When asked how many oceans there are in the world, the majority of people will likely respond “five.” However, the answer will be incorrect because in fact, there is only one ocean. Similarly, to the question of how many races exist, the answer must be along the same lines. There is only one, the human race. Unfortunately, we continue to use the wrong concept of identity as it has no scientific, biological or genetic basis. There are no races, except the human race. As long as we continue using useless concepts, such as race, that refers only to a social construct, we will continue to emphasise identities that are categorized in a way that exclude rather than include, divide instead of associating.

To understand the divergence of the human species in its anatomical characteristics, just imagine the metaphor of an ice cream stored in a refrigerator, divided into 4 parts and distributed in different places. Weeks later, when we open the refrigerator, we will find these same four pieces of ice cream with different shapes. However, the “ice cream” remains the same!

-

Conclusions

Individual, social, or collective identity is essentially a signalling and differentiation phenomenon characterized by regularity and contrast. It is the result of a need to distinguish between the inner self and the outside world, as well as the concept of “we,” the creators of groups, in relation to other groups in the outside world. In either case, whether from the “I” or “we,” identities recognize and mark the sentiment of existence.

There are many different types of social identity, which suggests that individuals are capable of signalling their group membership in multiple ways. However, in the process of social construction of identity, it is important to distinguish between the concepts of social groups (which are understood as sets of individuals with common goals, interaction, and mutual recognition) and the concept of social category, which is the result of stereotyped agglutination of individuals who while do not need to recognize each other or have common goals, they nevertheless have a common link that characterizes and distinguishes them from other categories, such as gender, origin or nationality (Hofstede, 2001). In this sense, it can be said that the vast majority of the so-called social categories are not groups, even though they provide the observer with an idea of identity.[22]

We discovered that, from an individual standpoint, the symbolic self-representation of someone as a member of a group implies certain costs, which means that in evolutionary language, the formation and marking of identities, as well as their signalling, have always been offset by the benefits of group membership, confirming the importance of social acceptance and the group’s need for survival in the ancestral and present environment.

Groups have always been fundamental to both survival and human identity. The overwhelming majority of us are part or linked to various groups throughout our lives and this results from common interests, affinities, characteristics or similarities.

In fact, according to the most recent research,[23] when a connection to a group has particular relevance in a situation or context that is also particular, the behavior itself will tend to follow the norms or rules of that group so that each element is considered appropriate. A study[24] suggests that the normative behavior of the group is also reflected in a person’s own writing style and that same style can reveal (with an accuracy close to 70%), which of the groups influenced a person while he was writing a particular piece of text.

In summary, identification with groups, whether tribes or their contemporary counterparts such as nations and ethnicities, suggests that the process of identity construction is associated with psychological processes and adaptive mechanisms that occur in the formation of group identities, but not in the formation of broader categories of identity, whether tribal or group.

From the evolutionary perspective, the phenomenon of social identity shows how humans have always had a need to gather together and developed a psychology of alliances as a means of survival, implicitly needing to mark and display their identity as a form of belonging and as a way of signalling their intentions and loyalties, and, above all, their ability to cooperate. In addition, group (or tribal) identity, allowed individuals to benefit from the protection of groups and to enjoy the benefits of cooperation within their group membership. It also allowed for competition with other groups in the fight for resources, dominance or influence over other groups. Therefore, group identity also functions as a mobilizing factor.

In a brief, whether in individual or collective terms, social identity appears to share something that stems from four needs. The first is a deep need to be acknowledged for one’s dignity or status, whatever it may be.[25]. The second is the need to distinguish oneself and stand out from the crowd. The third need is for coalition, inclusion, and belonging, which is driven by the fourth need, which is cooperation.

After all, we all come into the world prepared to play various roles related to different identities. This is how we manage others’ perceptions of us, with the ultimate evolutionary goal of getting along with others and thus achieving social progress in the groups that define who we are, confirming our need for recognition, existence, and lived experience.

Without identity, individuals hardly know who they are and to which groups they belong, and without knowing it, they rarely survive. And, perhaps most importantly, without survival there is no reproduction and that seems to be the ultimate purpose of genes.

References and recommending reading

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. (2009). Culture and the evolution of human cooperation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 364, 3281-3288.

Boyer, P. (2018). Mind Make Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Brewer, M. & Caporael, L. (1996). Reviving Evolutionary Psychology: Biology Meets Society. Journal of Social Issues Volume 47, Issue 3, pp. 187–195,

Brewer, M. (1995). In-group favoritism. In D. M. Messick & A. Tenbrunsel (Eds.), Behavioral research and business ethics (pp. 101-117). NY: Russel Sage Foundation.

Chambers, K. (1995). Sociolinguistic Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell

DeBruine, Lisa. (2005). Trustworthy but not lust-worthy: Context-specific effects of facial resemblance. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 272: 919-922. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3003

Durkheim, E. (1984) The Division of Labour in Society. London: Mcmillan

Finuras, P. (2020). Da Natureza das Causas. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Finuras, P. (2017). O Fator Confiança: a ciência para criar pessoas, líderes e organizações de alta confiança. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Finuras, P. (2014). Em quem confiamos? Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Finuras, P. (2013). O Dilema da Confiança – Estudos, teorias e interpretações. Lisboa: Sílabo

Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identidades. Lisboa: D. Quixote

Fukuyama F. (1995). Confiança. Variação internacional de valores. Lisboa: Gradiva

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity. Stanford: University Press

Giddens, A. (1994). Risk, trust and reflexivity. Cambridge: Polity Press

Hamilton, W. (1964). The genetically evolution of social behavior, I and II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7, 1-16, 17-32.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture and organizations. Comparing values, behaviours, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hoy, W. & Tschannen, M. (1999). Five faces of trust. Journal of School Leadership, 9, 184-208.

Hoy, W. & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2000). A Multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Review of Educational research, 70(4), 547-793.

Inglehart, R. (1991). Trust between nations: primordial ties, societal learning and economic development. In K. Reif & R. Inglehart (Eds.), Eurobarometer (pp. 145-85). London: Macmillan.

Kipnis, D. (1996). Trust and technology. In R. Kramer & T. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp. 39-50). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Klayman, J., & Ha, Y.-W. (1987). Confirmation, disconfirmation, and information in hypothesis testing. Psychological Review, 94, 211-228

Knack S., Zack P. (2003). “Building Trust: Public Policy, Interpersonal Trust, and Economic Development”, Supreme Court Economic Review, Vol. 10, pp. 91-107, The Univ. Chicago Press.

Knack, S., Zack P. (2001). “Trust and Growth”, Economic Journal, Vol. 111, No. 470, pp. 295-321, April, Royal Economic Society.

Mackie, G. (2006). Patterns of social trust in Western Europe and their genesis. In K. S. Cook (Ed.), Trust in society. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Messick, D., & Allison W. (1990). Individual heuristics and the dynamics of cooperation in large groups. Psychology Review, 102, 131-45.

Nakahashi, W. (2013). “Evolution of improvement and cumulative culture”. Theoretical Population Biology.83: 3038. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2012.11.001. PMID 23153511.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, T. (1977). Influence of subordinate characteristics on trust and use of participative decisions strategies in a management simulation. Journal of Applied

Psychology, New York, v.62, n.5, p.628-631, Oct. 1977

Tajfel, H., Billig, M., & Bundy, R. (1981). “Social Categorization and Intergroup Behaviour”. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 149-78

Tannenbaum, D., Ditto, P. H. and Pizarro, D. A. (2008). Different Moral Values Produce Different Judgments of Intentional Action. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Albuquerque, NM.

Van Vugt, M., & Park, J. (2010). The tribal instinct hypothesis: Evolution and the social psychology of intergroup relations. In S. Strummer & M. Snyder (Eds.), The psychology of prosocial behaviour: Group processes, intergroup relations, and helping (pp. 13-32). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Wursten, H. (2019). The 7 mental images of national culture: Leading and managing in a globalized world. Hofstede Insights. Amazon Books.

Zahavi, A. & Zahavi, A. (1997). The handicap principle: A missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Zack, P. (2010). Oxytocin Increases Generosity in Humans. Plo One 2, 11, 1128.

Zack, P., Kurzban, R., & Matzner, W. (2004). “The Neurobiology of Trust”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1032:224–227, 2004.

Zucker, L. (1986). Production of trust: Institutional sources of economic structure, 1840-1920. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational

Behavior, (vol. 8, pp. 53-111). Greenwich, Ct: JAI Press.

[1] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/identity

[2] According to some researchers, namely, Robert Boy, Peter Richerson and, Wataru Nakahashi, the classification of what is considered and included in modern human behavior implies a definition of universal behaviors among living human groups. Among the various examples of human universals, include abstract thinking, planning skills, commercial exchanges, cooperative effort, body ornamentation, as well as the use and control of fire. These characteristics imply social and collective learning. To know more, see Boyd, Robert; Richerson, Peter (1988). Culture and the Evolutionary Process (2 ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226069333 e ainda Nakahashi, Wataru (2013). “Evolution of improvement and cumulative culture”. Theoretical Population Biology.83: 3038. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2012.11.001. PMID 23153511.

[3] Animal Biology, Vol. 55, No. 4, pp. 297-321 (2005) ! Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2005. Also available online – www.brill.nl. On aims and methods of Ethology N. Tinbergen. Department of Zoology, University of Oxford. This paper was originally published as: Tinbergen, N. (1963) On aims and methods of ethology. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20, 410-433. This journal was renamed Ethology in 1986.

[4] According to P. Boyer, coalitions are simple forms of collective action applied to rivalries and between alliances, however, human beings are capable of creating collective action in many other contexts and forms (Vd. Boyer, Op. Cit. pp. 208-209)

[5] Billig & Tajfel, 1973

[6] Durkheim, E. (1984) The Division of Labour in Society. London: Mcmillan

[7] Chambers, K. (1995). Sociolinguistic Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell

[8] Robert Putnam. 2000. Op. Cit.

[9] https://ourworldindata.org/trust

[10] DeBruine, Lisa. (2005). Trustworthy but not lust-worthy: Context-specific effects of facial resemblance. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 272: 919-922. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3003 (University of Glasgow)

[11] See in this regard the so-called “minimum group paradigm” in Tajfel, H. (1971). In “Experiments in Inter-group Discrimination.” Scientific American, 223, 96-102

Tajfel, H., Billig, M., & Bundy, R. (1981). “Social Categorization and Intergroup Behaviour”. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 149-78

[12] Hamilton, W. (1964). The genetically evolution of social behavior, I and II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7, 1-16, 17-32.

[13] Cf. W.D. Hamilton, 1964 (Op.Cit).

[14] In social psychology the fundamental attribution error (FAE) describes how, when making judgments about people’s behavior, we tend to overemphasize dispositional factors and downplay situational ones. This means that we believe that people’s personality traits have more influence on their actions, compared to the other factors over which they don’t have control.

[15] Cf. Klayman, J., & Ha, Y.-W. (1987). Confirmation, disconfirmation, and information in hypothesis testing. Psychological Review, 94, 211-228

[16] Mackie, G. (2006). Patterns of social trust in Western Europe and their genesis. In K. S. Cook (Ed.), Trust in society. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

[17] Cf. Rosen Benson & Thomas Jerdee, 1977

[18] Cf. Hoy, W. & Tschannen-Moran, M., 1999, Five faces of trust, Op. Cit.

[19] That is, societies dominated by strong family ties and shared norms and where social interactions between people are strongly formalized

[20] Usually the term “motivated moral reasoning” is used to mean or describe situations in which the judgment that is made is motivated by a desire to reach a particular moral conclusion (Tannenbaum, et.all, 2018, Op. Cit.)

[21] We are aware that there is considerable debate and discussion about how to define “equal opportunities” in both philosophy and political science. Of course, it will be very difficult to envision a society that provides identical opportunities to all of its citizens. Here, my implicit definition of “equal opportunities” is not whether “equal opportunities” exist in general, but whether the state is capable of promoting this equality (Finuras, 2013).

[22] See also Huib Wursten about Mental Images and Identity in Wursten, H. (2019). The 7 mental images of national culture: Leading and managing in a globalized world. Hofstede Insights. Amazon Books.

[23] See “Changes in writing style provide clues to group identity.” ScienceDaily. 24 February 2021. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/02/210224090614.htm.

[24] By the University of Exeter, Imperial College London, University College London and Lancaster University

[25] This is what Francis Fukuyama calls “Thymos”. in Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identidades. Lisboa: D. Quixote

0 Comments