” How to take responsibility in today’s world:

What does it mean for the individual, group, and global society?

Looking for a multidisciplinary answer.

Author : Christina Röttgers

Synopsis:

Feeling overwhelmed and guilty in the face of recent and ongoing catastrophes and crises is for individuals in privileged countries on the increase and often coupled with a simultaneous sense of responsibility and powerlessness. This paper delves into the concept of responsibility across various societal levels – the individual, the group, and the global community – and offers some practical strategies for navigating this dilemma.

Moreover, it might serve the intercultural practitioner to shed a multidisciplinary light on a much-strained term.

The individual’s responsibility can be defined by their ethics, which are shaped by a value set defined by culture. While it seems obvious to hold individuals accountable, the extent to which responsibility can be attributed to groups and the global community is a complex matter. Thus, drawing insights from multiple disciplines becomes necessary to grasp the breadth of responsibility’s many possible domains and applications.

The extent to which groups can assume or be assigned responsibility, if at all, is a philosophical and sociological question of interest not only with regards to larger entities like nations but also to teams within organizations. Is their culture pivotal in fostering a sense of responsibility? Can a collective sense of responsibility translate into tangible accountability? Yet, from an intercultural perspective, also the meaning of responsibility varies and will be explored in this article.

On a global level, responsibility must be reflected in line with the purpose of politics which fundamentally differs from the purpose of cross-cultural research.

Ultimately, this article aims to present practical avenues for addressing the perceived dilemma of feeling responsible yet powerless, and to provide tentative answers to the pressing question that resonates with all responsible individuals: What can we do?

Keywords: Responsibility, Ownership, Philosophy, Individual, Ethics, Groups, Teams, Culture, Global, Multi-disciplinary, Politics

Introduction:

In today’s world it seems increasingly difficult to either take or assign responsibility.

Numerous aspects contribute to why that is the case. This paper aims to explore several of these aspects focusing on varying perspectives at the individual, group, and global levels with the consequences for teams probably being the most tangible within organizational contexts.

While this exploration incorporates multidisciplinary viewpoints, the primary lens through which this text operates is philosophical. Therefore, readers should anticipate encountering numerous questions, perhaps outnumbering the answers provided, as philosophical inquiry traditionally centers on posing significant questions.

Responsibility: a term seeking an answer

The term “responsibility” inherently communicates a message, as it comprises two distinct words: “response” and “ability.”

This linguistic construct is not exclusive to the English language; it resonates similarly across various languages. In German it contains the word “Antwort” (engl. answer) in “Verantwortung” (engl. Responsibility), in French “Réponse” (engl. response) in Responsabilité, in Russian the word “Otvet’” (engl. answer) in the word otvetstvennost’, in Irish “freagra” in “freagracht”, in Swedish “svar” in “ansvar”. Across these languages, “responsibility” conveys the notion of needing to have an answer to be able to take on responsibility or – in an even broader sense – to be able to respond. If we take responsibility, we do what we think is right, we do what reflects our answer to an issue. In English and French, in particular, the term also implies the capability to respond effectively, suggesting that mere knowledge of an answer might be insufficient without the ability to respond and act upon it. So, there is a clear threshold for taking responsibility and being held responsible. This nuanced understanding is – to take it a step further – reflected in European legal frameworks, where the culpability of defendants is a precondition of their sentencing.

If we claim responsibility from others, we expect them to do what we think is the right thing to do, what we think is the right response. It is important to be aware of this when trying to assign responsibility to others, as it presupposes a shared or at least understood perspective of what constitutes the correct response or answer. This aspect is not easy to ensure when delegating responsibility among people from the same culture, it is even more challenging across cultural boundaries, where differing perspectives may complicate alignment on the appropriate response.

For instance, imagine a manager tasking a team member with planning an event but the team member misses enough information about the goal and invitees. It is not clear why the information is missing, whether the manager has not given it or whether the team member has not properly followed up. In any case, without mutual understanding, it becomes challenging to hold the team members accountable for the event’s success.

So, how do we know how to act to take or assign responsibility? Do we have an answer?

Different disciplines give different answers.

Throughout history, philosophers were engaged with the question of what constitutes right action, how to act in a good way seeking absolute truths and non-questionable answers. The traditional (continental) European philosophies until the 19.c. tried to find the universally accepted definition of “good” – like for example Immanuel Kant with his categorical imperative: „Handle nur nach derjenigen Maxime, durch die du zugleich wollen kannst, dass sie ein allgemeines Gesetz werde.“ (“Act only according to that maxim through which you can at the same time want it to become a general law.“)(Kant, 1785).

These kinds of maxims assume that we all think the same way, so that everyone would come to the same conclusions about what should become a general law and what should be done.

However, in the realm of intercultural theory – as all interculturalists know – there is no common idea of what is good across societies. It is rather relative what is seen as good or not. So that the absence of a universally accepted notion of the “good” highlights even the relativity of what is seen as good across diverse societies globally. This perspective, however, represents the opposite of the traditional European philosophical thinking and was exemplified by Geert Hofstede’s assertion: „The survival of mankind will depend to a large extent on the ability of people who think differently to act together “(Hofstede, 2010).

Thus, with the rising importance of intercultural theories thinkers needed to switch from the pursuit of a last undeniable truth about the right acting to embracing the relativity of all values and to promoting understanding of different ways of thinking. The non-judgmental descriptive approach of cultural anthropologists provided new perspectives and enabled mutual understanding. The tension between these opposing approaches can still be found today, not only between philosophers and anthropologists, but also in politics, because what suits interculturalists as a necessary, neutral approach for mutual understanding, will not provide sufficient answers in politics.

Politics are per se prescriptive and not descriptive. They must adopt a position instead of neutral observation. The democratic Western states have lately been in a challenging situation. After centuries of colonialism, they seem to have forfeited their credibility to strongly claim their values as basis for global politics. At the same time, so far, we haven’t found another political system that ensures individual freedom, freedom of opinion and freedom of speech than the democratic one. To what extent shall therefore the democratic states promote their democratic values globally? Hence, the question of ‘how to act together despite thinking differently’ is also a fundamental one for global politics.

Below shall be highlighted a few examples of various disciplines giving different answers to questions stemming from the same problem: ethics, cultural theory, and politics.

Each of these disciplines provide their own answers and if there might be one “absolute” truth: than that we need all these disciplines and especially, all these answers to find a way of acting responsibly on a global level.

Different societal levels and how they relate to responsibility.

The individual.

While reflecting on responsibility, something can be observed more often: individuals looking at overwhelmingly global problems tend to feel kind of responsible for or challenged by them amid a sense of helplessness. There is the realization of the need to change course in the face of climate change and the wish to help reduce the many humanitarian problems, conflicts, and wars.

Yet, at the same time individuals ask themselves what they personally can do.

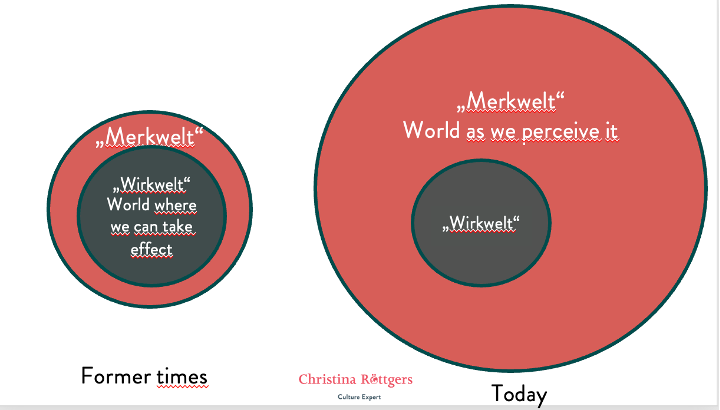

From a philosophical perspective the growing unease of individuals can be explained: modern advancements, such as globalization and technology, have increased the complexity and disparity between the world individuals influence or impact, the so-called “Wirkwelt” (world of impact) and the world individuals perceive, the “Merkwelt” (world of perception) (Husserl, 1936. He refers to the Wirkwelt as the real world though.). These two worlds used to be almost congruent for the longest time in history. The news our ancestors received were usually ones they could act on or deal with directly. Nowadays though, all information is available almost instantly and the challenge is to choose the information we want to receive as it has become impossible to deal with all available information. At the same time, our zone of influence is usually much smaller than the zone where we can take effect. (figure 1) We are for example informed about developments in the world far out of our personal reach. This means that we perceive much more than we impact and that is, what creates in some individuals a feeling of being overwhelmed, powerless or helpless.

Figure 1: The increasing gap between the world of perception and the world of taking effect.

So, what can we do ourselves considering this awareness?

What could give us guidance for our actions?

One way of navigating these questions is formulated by the philosopher Hans Jonas in his book “Das Prinzip Verantwortung” (The Principle of Responsibility), which he wrote already in 1979. It represented a switch from older ideas of ethics, solemnly focusing on the individual and being anthropocentric, to the impact of humanity and its technological developments.

His imperative reads:

„Handle so, dass die Wirkungen deiner Handlung verträglich sind mit der Permanenz echten menschlichen Lebens auf Erden.“ (“Act so that the effects of your action are compatible with the permanence of real human life on earth.”)(Jonas, 1984).

This includes the idea of sustainability of our actions within our personal responsibility.

While his principle seems very logical and might be easy to accept in theory, it seems impossible to follow. The complexity of modern global dynamics makes it challenging for individuals to foresee the consequences of their actions fully.

In the fashion industry, for example, it is difficult to determine whether it is better (more sustainable) to produce locally, thereby avoiding the impact of transportation, or in developing countries, thus providing more economic opportunities for the poorer population. Which production location is, therefore, more ethical?

For interculturalists and politicians Hans Jonas’ imperative presents a similar dilemma to that of Immanuel Kant: universal acceptance would be required across all societies globally to enable collective action. Unfortunately, the recent COP 28 in Dubai, for example, highlighted that this consensus has not yet been achieved.

Nevertheless, how do we, as individuals, intend to address this dilemma? Individual action does not necessarily require a global consensus.

There are films like the documentary “Tomorrow” that explore various worldwide initiatives aimed at creating a more sustainable future – not solely in an ecological sense. Among other stories, it showcases individuals who have devised their unique approaches to assuming such responsibility (https://www.tomorrow-documentary.com). For instance, it follows a French couple who transitioned from careers in law to pursue permaculture farming. Another narrative features a village in India where residents have implemented a truly democratic approach to address neighborhood issues, fostering coexistence among diverse castes. However, for many, drastically altering their lifestyle may seem daunting. Yet, each person can contribute in some way.

Embracing practical approaches and acknowledging that there isn’t a single, overarching solution may serve as starting points. “Tomorrow” vividly illustrates that there is no one-size-fits-all solution, but many, offering relief from the overwhelming burden often felt by individuals. The top 5 already existing solutions for democracy, education, economy, energy, and food are presented also in a blog. Our personal responsibility might not be to solve all the problems, but addressing one issue by every individual would already be a huge step forward.

A conclusion for individuals could be to strive to make a difference within their sphere of influence, their “Wirkwelt,” where they can exert tangible impact. It’s advisable to concentrate on one problem or issue that resonates most with us, rather than attempting to address too many at once.

If every individual embraces this approach, collectively we can make a significant impact.

Groups – and how they relate to responsibility.

The group perspective is arguably the most complex and challenging one of all categories.

Examining how groups relate to responsibility requires an understanding of what defines a group and the characteristics that make a group suitable for assuming responsibility. This is because, just as with individuals, any kind of group exists due to differentiation.

This raises questions: How do we differentiate? Which groups warrant examination? The challenge of these questions needs to be included in the understanding and claims of diversity. By defining minority groups requiring better recognition and support, we distinguish them from the majority. Ideally, successful inclusion would render discriminated minority groups indistinguishable from the broader society.

Considering these points, we must ask ourselves:

What groups should we create and when?

What groups do we belong to, or wish to belong to?

What groups should we actively engage in, and which should we analyze?

Shall we look at ethnicities, nations, or colors at all

In Germany, statistics regarding ethnic backgrounds are mostly forbidden – for good reasons due to lessons learned from the racist persecutions and horror during the Nazi time which were partly facilitated by collecting ethnic data.

Yet, if we are to define suitable responsibilities for groups, we need adequate data upon which to base our decisions. Many answers can only be provided if groups are systematically examined. The discrimination of a certain group can be better proven and addressed if relevant data about that group is available. For many groups, such data is lacking.

A great example was recently provided by Caroline Criado-Perez in her book about the gender data gap. She demonstrates how the absence of data about women, and consequently, the ignorance about their needs and behavior, prevents not only women but entire cities and societies from finding better, cheaper, and more sustainable solutions in all areas of life (Criado-Perez, 2019).

So, this argues for obtaining as much group-relevant data as possible. Again, we face a dilemma: Is it better to obtain the data or to protect individuals’ data? Does individual data protection offer better safeguarding for discriminated groups than an informed analysis of specific group data, which could help avoid bias against certain groups? However, the downside is that the data could also be abused to fuel stereotypes and bias.

Even if we had data, are we able to respond in the sense of being responsible as a group?

Is there such a thing as a group responsibility? If so, it would necessitate an extremely strong identification with the group, implying firstly being a member of the group and secondly being ready to take responsibility for the actions of all group members collectively. What are the pre-conditions of such strong group identification?

One might consider a sports team, for example, where individuals unite for one common goal, or families.

However, could such group identification, leading to group responsibility, extend beyond a group of people that one personally knows, if at all? Could it be expanded to the national level? Could all citizens of a country be responsible if the country’s government acts irresponsibly? Would it make a difference regarding the responsibility of a population if the government were democratically elected or if the population had limited choice?

These are the challenging additional questions that arise when contemplating group responsibility.

Teams in organizations

A special case of groups are teams in organizations. They are defined by a common goal, and there is an increasing trend towards assigning responsibility to the entire team.

The typical ingredients of a successful team, such as a common goal, clarity of the goal, and trust, are prerequisites for being able to act responsibly. While the common goal and trust strengthen the identification with the team and its purpose, the clarity of the goal ensures the ability to act in the intended manner.

From an intercultural perspective, it is particularly intriguing how clarity of the goal is achieved. This starts with questioning how the goal is communicated. The use of more direct or indirect language will have different effects depending on the cultural backgrounds of the team leader and members.

Another important consideration is who should ensure an understanding of the goal. In countries with lower power distance, it would be expected for the team members needing more information to equally ensure the correct understanding of the goal. Conversely, in countries with higher power distance, it would be seen as the full responsibility of the boss to provide all necessary information.

Returning to the example of event planning, the question encompasses not only whether the expectations were clearly understood but also how all necessary information could be acquired. Depending on the cultural background, the responsibility for providing or obtaining the necessary information can be on the boss or the team member.

Consequently, one may question whether responsibility is assigned at all, or rather, only tasks. While in countries with a lower power distance, it is typically understood that the assignment of a task also transfers the responsibility for its success, in countries with a higher power distance, an assignment would be more commonly seen as merely delegating tasks. This can create a lot of misunderstandings in multinational teams and affect their joint responsibility.

The collective sense of responsibility in a team is also influenced by the rules for remuneration and acknowledgment. In individualistic countries, it will always be seen as a stronger motivator if individual contributions are measured and acknowledged. In more group-oriented countries the opposite might apply where the team might deliver better results if the individual contributions are not tracked. The latter scenario is perhaps the closest case to where one could speak of the responsibility of a group.

Global responsibility

By introducing the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), the UN has outlined the most significant challenges for the international society to address. Goal number 10 (reduced inequalities) underscores an inherent problem that must be tackled in conjunction with several other goals (no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, etc.). Addressing inequality, however, is closely tied to the redistribution of power, shifting from men to women, from the super-rich to the poor, and from the West to the Global South.

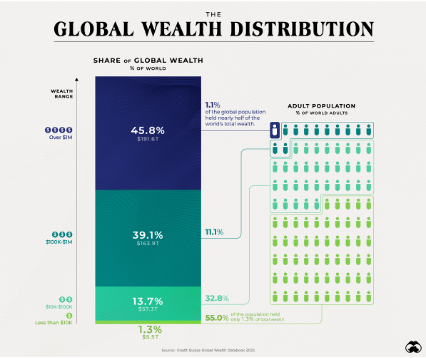

Data on the distribution of global wealth is particularly illuminating in this context. (figure 2)

Owning a house or an apartment likely indicates that individuals belong to the 12.2 percent of the world’s population that owns 84,9 percent of the world’s total wealth as of 2021.

This wealth is partly sustained by the fact that, as of today, 40 million people (according to the International Labor Office, ILO) are still victims of forced labor, which must be seen as modern slavery. (figure 3)

The website http://slaveryfootprint.org offers insights into how a luxurious lifestyle, or even one that consumes more than necessary, is upheld by a system of slavery. By exploring this website, individuals can comprehend, assess, and monitor these connections.

For many of us, residing in some of the most privileged societies globally, this realization prompts the understanding that achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of reduced inequality necessitates being among the first to relinquish portions of our wealth and power.

Are we ready for such a shift? If we did, would that lead to more balance?

Or would the renunciation of power and wealth by those who actively try to achieve the goal of reducing inequality reinforce the non-democratic developments of those who ignore this goal? Would politicians act against their oath – to act in favor of the people who elected them – if they were willing to share more power and wealth globally?

In any case, addressing global responsibility necessitates a reimagining of our economic system to incorporate environmental and sustainable values. Kate Raworth, for instance, has developed the “Doughnut”-Model of Economics, challenging the paradigm of endless economic growth and advocating for an economy that avoids environmental overshoots and social shortcomings (Raworth, 2018). Encouragingly, cities like Amsterdam and nations like Costa Rica are already embracing this model and adapting their economic concepts accordingly.

Furthermore, a new approach is required for measuring the economic success of societies beyond the traditional GDP metric. Marilyn Waring, researcher and MP in New Zealand, was among the first to critique GDP for measuring the wrong indicators, such as drug smuggling and sex trafficking, while overlooking essential economic sectors like unpaid care work and, by that, setting the wrong priorities in politics (Waring, 1988). Her TED Talk elaborates on this perspective, which has since gained traction among many others.

Summary and outlook

Ethics for an individual often revolves around the idea of an absolute, universal standard of moral behavior.

However, from a cultural perspective, achieving such universality is not feasible. The neutral descriptive approach of anthropologists enables mutual understanding among cultures.

It is in politics, where cultural values often collide, as the purpose of politics is to establish common rules. International order can only be maintained if a basic set of values and rules is shared.

Feelings of helplessness among individuals may stem from a lack of differentiation between their immediate environment (‘Wirkwelt’) and the broader conceptual world (‘Merkwelt’) or from uncertainty about whether they are acting as individuals, as group members, or as politicians.

Identifying the pertinent questions is a prerequisite for finding answers at various societal levels and within different disciplines. This will finally enable us to take responsibility.

In an increasingly complex world, value-based leadership will be essential for finding solutions. Values will provide guidance and will make us responsible as we can derive answers to multiple problems and questions from them.

According to Keith Grint, value-based leadership is needed to address so-called wicked problems. These are complex problems that surface and really don‘t have any obvious solution; they hold a multitude of other problems within them. The leadership role is not to overcome these problems but to ask the right questions within them. Such problems require leadership that involves everyone and approaches that investigate every possibility. The COVID-19 pandemic was a typical example of a wicked problem.

Intercultural Sensitivity that makes you attentive to signals and open to multiple perspectives will encourage the search for multiple options (Brinkmann, 2014).

Since the solution to wicked problems cannot be obtained by rational conclusions only, values and emotions become more and more important for finding the right way to address such problems. Therefore, an understanding of the diverse values of different cultures and collaborators is necessary for true compliance. Furthermore, leaders who have flexible communication styles and can create commitment will certainly be more successful in achieving collaborative compliance within their team, and as such, these teams will be more responsible and resilient.

„ Leadership is taking responsibility for your own world,” Karen and Henry Kimsey-House say, “let‘s all be leaders.”

Literature and websites:

Brinkmann, Ursula & van Weerdenburg, Oscar – Intercultural Readiness. Four competences for working across cultures – Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Criado-Perez, Caroline – Invisible Women. Exposing data bias in a world designed for men – Vintage, 2020.

Grint, Keith – Problems, problems, problems: The social construction of leadership – Human Relations 58(11), 2005.

Hofstede, Geert, et al. – Cultures and Organizations. Software of the mind – McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Husserl, Edmund – The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology – 1936.

ILO – Global estimates of modern slavery: Forced labour and forced marriage

International Labour Office (ILO), Geneva, 2017

Jonas, Hans – Das Prinzip Verantwortung. Versuch einer Ethik für die technologische Zivilisation – Suhrkamp, 1984.

Kant, Immanuel – Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten – 1785.

Kimsey-House, Karen & Henry – Co-Active Leadership: Five Ways to Lead – Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2015.

Raworth, Kate – Doughnut Economics. Seven ways to think like a 21st – Century Economist, Penguin, 2018.

Waring, Marylin – If Women Counted. A New Feminist Economics – Harper & Row, 1988.

Waring, Marylin – TedTalk: https://www.ted.com/talks/marilyn_waring_the_unpaid_work_that_gdp_ignores_and_why_it_really_counts

Blog of the film tomorrow with top 5 solutions for democracy, education, economy, energy, and nutrition https://www.tomorrow-derfilm.de/blog.html

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_575479.pdf

0 Comments