Cultural congruency and conformity in two types of Diaspora

Dr. Luc Zwaenepoel

Abstract: This essay is researching transnational cultural processes by having two types of diaspora: the Congolese community in Brussels and the Hasidic Jewish community in Antwerp. Research is done by the key terms in migration culture: congruence, conformity, adaptation, and acculturation. In the Congolese context in urban Belgium, the cultural identity is hybrid, transnational with multi-scalarity and diasporic citizenship. The Jewish Hasidic community and diaspora have a cultural identity based on strict religious laws that makes it difficult to adapt to the Belgian and European cultures.

Keywords: migration cultures, cultural identity, Matongo, diaspora, Congo, Hasidic, congruency, conformity

The context: The natural demographic movement of emigration and immigration is not new and is part of changes in important world demographic data and the national economic planning of services and goods.

Essential types of migrants are guest migrants, seasonal migrant workers, labor migrants, family reunion migrants, climate refugees, war refugees, and Persons of Concern for UNHCR (refugees, asylum seekers, stateless persons) a group under international protection (UN, EU) and the international students.

The general public is often not making a difference between migrants and refugees, between economic migrants and labor migrants, and between climate refugees and displaced persons by conflict. All are seen as immigrants or transit immigrants.

In his essay, the term “migrant” will be used in the text.

The migration culture and the psychology of immigrants and emigrants are often mistaken and not seen as windows of opportunity for the National Economy to solve the shortage in labor and health service providers because of an ageing population.

Emigration is the movement of skilled and less skilled labor and their families to countries with more economic and social opportunities. As was seen before, with the Dutch/Belgian emigrants to Canada, the USA (the Red Star Line), the Guest workers to Northern Europe in the golden sixties and the surviving Jewish population who stayed in Western Europe.

Immigration is the other side of emigration and has the same demand and supply, push and pull principles in place.

Countries in Western Europe favored immigration (even with State aid) when the economy was booming in the sixties and national full employment was reached. Many Maghreb Africans, Turks, and Greeks have been called in to contribute to the economic welfare of Western economies. Some went back, and others stayed in the new countries and “integrated”.

This paper researches several themes that are widely discussed as more migrants reach the shores of “Fortress Europe” and international funds are available to Sub-Saharan border states to keep African migrants in Africa.

The cultural beliefs and social patterns that influence people to move. (12,20)

Cultures of Migration combines anthropological and geographical sensibilities, as well as sociological and economic models, to explore the household-level decision-making and risk-taking processes to leave the home country.

Even in countries where risk-taking and long-term vision are low, following Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, one can see that migrants are forced to leave their home country or send their young ones over the borders to Europe. The main reason for a high-risk take is the perception of the aggravation of their environment, economic misfortune, war and terror. But also, in the category of climate migrants is the impact of climate changes on rain-fed agriculture an indicator of more migration in Southwards.

African migrants do have strong links with their ancestral land, the tribal community and the extended family. To leave all these behind is also fed by the wrong perception of life and the economy in the West. Access to social media and Western movies intensifies the idea that a better life in another place is a possibility for better health care, education and social security. Often the departure of a young family member is sponsored by the family and by the community as a safety line for sending overseas remittances. Another aspect is the fact of having relatives in a faraway country that can lead to future family reunification.

Migrants are strong-willed people and high-risk takers, even willing to end up in the Mediterranean Sea as one of the many Africans that never reached” Fortress Europe”.

On the side of the receiving European countries, there is also the belief that all migrants are coming to steal their jobs and that migrants are a threat to change their race ratio. In reality, European countries with existing natural borders and hindrances to entry and a strict migration policy, are one of the least continents for migrant entrance per population per capita.

Countries like Lebanon, Turkey, and Uganda do have much more migrants of all sorts on their territory.

The cultural aspects in this situation are that countries with high risk-taking and with long-term visions are not taking the risk to receive more migrants (EU quotas) and have a short-term vision on the demographic indicators and the real needs to maintain the quality of their productive economies by allowing more migrants in Europe. Long-term planning without an extensive international dimension leads to shortages in labor for health centers and education personnel.

This is after the Corona period seen in the HoReCa sector, where companies are offering more fringe benefits to attract and keep workers.

Another important aspect is the language and the understanding of socio-cultural arrangements in the future host country. This is less of a problem for fluent French or English speakers. The language is only a part of the cultural and social patterns in the host countries. For some migrants that part of the equation is not fully understood. Often elderly migrants in a family reunification arrangement, speaking only their mother tongue, are lost in their new society and dependent on the assistance of the grandchildren going to school and speaking the language of the country.

The wrong assessment of social beliefs and new patterns leaves many older migrants close to depression and are the cause of mental illness that is not treated.

Understanding the demographic dividend of the African continent versus the demographic deficit of the Western countries (13,14)

The map of world demographics shows exactly the shift of population migration from so-called countries in development towards developed countries. The Club of Rome, a club of wise men, already indicated that the “population bomb” will have dire consequences on the environment, food production, health and conflict. They calculated in 72 that the world population is going to have exponential growth, at present, we are 7.888 billion in 2023.

Many scientists think Earth has a maximum carrying capacity of 9 billion to 10 billion people.

The limits of economic growth and the population increase will be seen in the twenty-first century. The Club of Rome’s main focus is on global problems associated with population and economic growth. It espouses a neo-Malthusian agenda of limiting population growth and promoting sustainable economic development to address perceived problems of environmental degradation. (13)

What is the Malthusian theory? (14)

Malthusianism (1798) is the theory that population growth is potentially exponential, according to the Malthusian growth model, while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population decline.

What can be learned from these theories and predictions on the state of the world that were made in 1972 by the Club of Rome? In the frame of this essay, it is evident that the Club was right after 50 years that the population and the unlimited economic growth had an impact on the environment and the quality of life.

Concerning the very old Malthusian theory, the reality is that the population growth and the production of food supply in the world have been significantly changed over the year by new techniques ( family planning, agricultural techniques and planning), global extensive transport means and communication lines

The three correctors of Malthus on population growth were: war, sickness and disaster.

Malthusian population theory suggests that a reduction in the population pressure on existing resources through emigration could trigger a rise in birth and survival rates in the sending population.

in 1798 in Thomas Robert Malthus’s piece, An Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus believed that the population could be controlled to balance the food supply through positive checks and preventative checks. These checks led to the Malthusian catastrophe.

The population theories about World population growth have been dated but it explains partly the phenomenon of immigration worldwide and especially from Sub-Saharan Africa to Europe. European demographic deficit is not caused by natural elements, catastrophes or warlike situations, changes are because of the high increase in the quality of life, the change in family structures, the decrease in children born per family, in new contraception, more women with a professional career and the rising costs of raising a kid towards adulthood. The Replacement-level fertility of a population is based on a Total fertility level of about 2.1 children per woman. This value represents the average number of children a woman would need to have to reproduce herself by bearing a daughter who survives to childbearing age. In most European countries this ratio is less than 2.

On the African side is the population growth still high because of the need for future labour in subsistence agriculture and the social care for ageing parents.

Population corrections in Africa are still in place like war, conflict, drought, natural disasters and climate change.

The demographic dividend of Africa:

The demographic dividend is the economic growth brought on by a change in the structure of a country’s population, usually a result of a fall in fertility and mortality rates. The demographic dividend comes as there’s an increase in the working population’s productivity, which boosts per capita income.

Demographic deficit (Europe) is generally the reduction in wealth due to the ageing of the population and in the financial context, the increase in the budget deficit due to the ageing of the population.

The push and pull factors of immigration are largely due to the perception of cultural processes (type of work, mentality, religion, and social arrangements) as in Europe. Also, the need to build up a better life for the individual and the family is important. Another push factor is the change in climate as rain-fed agriculture is largely depending on clear cycles of rain seasons. Young Africans, inspired by access to larger information, media and social tools, are pulled by often not realistic images of wealth, easy work conditions and the absence of conflict and war.

The demographic transition of immigration of course does have important changes in the social fabric of European cities and villages but also leads to some clashes of cultures and different social arrangements (turf and race).

The African migrant or newcomer is not always welcome, seeing the many obstacles to arrival and the high risk of losing his own life. However, the European attitude is biased on the one hand giving high amounts of international funding to Maghreb countries to keep migrants in Africa. On the other hand, allowing migrants with high skills to work in sectors that are craving for new personnel is the case for nurses, elderly caretakers, ICT and workers that can fulfill tasks that Europeans are not interested to do anymore.

This double take on immigration by Europe is calling for problems in having a clear perception of integrating new migrants into our societies.

The cultural aspect of this societal change in the last decennia and the upcoming years has been already fully debated. All kinds of discussions led to solution-seeking proposals: like creating diaspora hubs (“quartier Matonge for DRC and the Great Lake countries in Brussels), integration and language courses and curriculum, and increasing multicultural events to showcase exotic cultures.

The Hofstede approach is therefore based on the full understanding of the national cultural values (6D) and finding common ground by explaining the fundamental differences.

The described push and pull factors to explain immigration has two cultural components that for Africans are not common in their national culture: the high risk-taking and the long-term view.

Cultural identity and cultural bereavement ((3,12,20)

Upon the arrival of the migrant main questions are: How to adapt in the short term: to the language, the social arrangements, the administrative rules, the housing, the food, the education, and the medical care?

Problems of loss, cultural bereavement and disillusion after arrival lead to depression and feelings of loss.

Loss of the family structure and the loss of power and authority in the extended family structure. (Ubuntu context) (11,17,28)

Ubuntu is not only “I am because We are” and also “We are because I am. ”

Ubuntu is based on Orunmila (Odu Ifa verses) and stresses that Ubuntu means the “dance of being”. Its holistic humanistic vision is “Me and us” but also “We and the others”. (17)

This is visible in the Bantu philosophy of the Congolese living in the diaspora in Europe and the US. It facilitates adaptation and avoids acculturalization.

Cultural identity and cultural bereavement can be seen in the diaspora communities in different cities of Europe. This research will examine two diaspora communities existing already a long time in Brussels, Belgium: The Congolese Community around Brussels and the Hassidic Jewish community in Antwerp, Belgium.

Congolese Diaspora in Brussels (Belgium) ((4,6,7,8)

The Congolese migrant is over the years an important community in Belgium as well as the migrants from Rwanda and Burundi. This was a natural movement after the Independence as we see also the same migration patterns from West Africa to France in the sixties.

The Congolese community in Belgium is important and very well organized. They have a reference point in the center of Brussels called Matonge after the name of a famous quartier in Kinshasa. Matonge is the window on all that is Congolese culture and small business (food, hairdressers, colored clothing, handicrafts and music.)

The cultural identity of Congolese migrants living already long term in Brussels is still very African as a strong link exists with the homeland, the tribal village of the ancestors and the sending of remittances to elders and family.

Most Congolese have double nationality and had an education and schooling following the Belgian curricula. They often speak different languages and the French language and Lingala is the lingua franca.

The difference in cultural dimension between Belgian and Congolese culture (9,1

| Cultural dimensions | Belgian | Congolese culture (Bantoe) |

| Power distance | 65 | 79 |

| Individualism | 75 | 28 |

| Masculine | 54 | 71 |

| Uncertainty avoidance | 94 | 91 |

| Long term vision | 82 | 7 |

| indulgence | 63 |

Source: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool,countries

The most important difference is Individualism versus collectivism (22,23)

Most Africans have a cultural shock when they are confronted with the individual approach, the small family unit, the lack of cohesion in the big cities, the cold shoulder in case of difficulties and the nonexistence of an extended family, only visible during marriage and funerals.

The Congolese community is based on solidarity, tribal recognition and respect for the elderly. (Ubuntu)

After years of living in Belgium, the migrant gets used to the Belgian externalities of their culture. They have acquired several do’s and not do’s to integrate and conform, but their cultural values still exist and only change after a long time. Two Congolese in New York will be even more Congolese when they are abroad.

But how are Congolese youth as the third generation coping with Cultural identity? (3)

Some findings from a large international study of the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant youth (aged 13 to 18 years) who are settled in 13 societies (N= 5,366), as well as a sample of national youth (N= 2,631). The study was guided by three core questions: How do immigrant youth deal with the process of acculturation? How well do they adapt? What is their cultural identity?

There were substantial relationships between how youth acculturate and how well they adapt: those with an integration profile had the best psychological and sociocultural adaptation outcomes, while those with a diffuse profile had the worst; in between, those with an ethnic profile had moderately good psychological adaptation but poorer sociocultural adaptation, while those with a national profile had moderately poor psychological adaptation and slightly negative sociocultural adaptation. Implications for the settlement of immigrant youth are clear: youth should be encouraged to retain both a sense of their heritage and cultural identity while establishing close ties with the larger national society. (3)

Our focus here is on a particular ethnic group in Belgium, namely the Congolese diasporic ‘community’. Its particular atypical history of migration and the presence of a large number of residents of Congolese origin in Brussels bring out a series of processes of hybrid identity formation that are underrepresented in the literature on European urban transnational immigration. The Congolese diaspora offers a uniquely important and extraordinarily rich group who have formed a particular transnational, but locally embedded, ‘hybrid’ identity, shaped exactly by their particular histories, geographical trajectories, scaled networking, and urban embedding. Moreover, the rapid growth of a population of Congolese descent was marked by the transformation of a neighborhood in Brussels (Matonge) into a distinct, globally localized ‘African’ community, a transformation that coincided with the acceleration of globalization.

The estimate is that the Congolese diaspora in Belgium totals more than 80,000 individuals. Congolese immigration is atypical, particularly as most migrated through personal choice and not as a result of active migration policies from the Belgian state or of special post-colonial arrangements. (4,6,7,8)

Transnationalism and hybrid cultural identity (19)

Transnationalism’ is defined as:

“…[t]he processes by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement. We call these processes transnationalism to emphasize that many immigrants today build social fields that cross geographic, cultural and political borders. Immigrants who develop and maintain multiple relationships – familial, economic, social, organizational, religious and political – that span borders we call trans migrants.”

Source: The Congolese diaspora in Brussels and hybrid identity formation: multi-scalarity and diasporic citizenship Eva Swyngedouw & Erik Swyngedouw https://doi.org/10.1080/17535060902727074

Source: Matonge mural by Cheri Samba https://bdmurales.wordpress.com/2010/06/17/cheri-samba-porte-de-namur-porte-de-lamour/

Cultural duality in the second generation of migrant children ((3,4,6,7)

Young generations originating from the Congolese community adapt easily to the cultural duality of being Congolese and being Belgian/European. This is facilitated by having access to the Belgian education curricula and multilingual skills in a Belgian urban context.

Conclusions for the Congolese Diaspora in Belgium (12,18,20)

Cultural congruency and conformity

The Congolese community being part of the long history and the colonial past makes cultural congruity and conformity with the Belgian society and values easier. The older and the new arrivals encounter some problems in adaptation but are assisted by the Congolese community with a strong sense of solidarity.

Cultural congruity: The finding of common ground between cultural values concerning differences and religious attitudes. This is the case in Brussels, where the Congolese community is assimilated and adapted. The fact that the Congolese community is merely from a Christian background facilitates congruity. This is not always the case with migrant communities of different religions like Islam from the Maghreb or Arab countries. (See: multicultural mural Matonge)

Cultural assimilation or the process of groups of different heritages becoming part of the existing national cultural dimensions and acquiring basic habits, attitudes and modes of life of an embracing culture.

In the third generation of the Congolese community, assimilation is strong as most have been going through the Belgian school system and often have only Belgian nationality.

Amalgamation is perhaps the word for the cultural process it refers to a blending of cultures rather than acculturation. The blending of the two cultures is possible in the multicultural urban context of Brussels and less in the rural areas. A good example is the existence of the “quartier” Matonge as the center of Congolese culture in Center Brussels (see Mural)

The process of integration, naturalization (15,16,18)

Because of the hybrid cultural identity of the Congolese community, the process of integration is more feasible without losing the side of their tribal origins. This is the case of the third generation of Congolese youth, who easily assimilate into the Belgian context. Congolese ” migrants” have a strong place in Belgian society, in politics, in church, the administration, the police force and in the educational system. A good example is the Belgian National football team (called the Red Devils). Half of the team are African Belgians of the third or fourth generation. This is also the case for the National Football Team of France as most players are naturalized and have double nationality.

Ethnic, cultural diversity: the Hasidic community in Antwerp, Belgium (21,25)

A second case to illustrate cultural congruity and assimilation is the Hasidic and Jewish communities living in Antwerp, Belgium. In this essay, we will not go into detail to describe the differences between Hasidism, orthodox and non-orthodox communities. The Hasidic community lives already since the 15th century in Antwerp as it was a famous place for the diamond trade in Europe(1). Nowadays taken over by Indian and other centers for the international diamond trade. Almost 20000 Hasidim are living with their families in Antwerp center, in what is called the Jewish part of the city near the Central station. The Hasidic religion is based on strict observance of the laws (613) and has a strong sense of hierarchic community life with all institutions and rules in place. There are of course in Antwerp non-orthodox Jews, not living in communities and more integrated in the Belgian society.

Yiddish is spoken by most orthodox Jews, making Antwerp one of the few Yiddish-speaking centers in the world. For years, Yiddish was the language used in the diamond trade. But most Jews speak French, Hebrew and in less order Dutch. The main curriculum in school is lessons in Dutch, except for issues related to their religion.

The Hasidic community in Antwerp has a strong sense of community belonging. A good example is the existence of the “Eruv.”

As in other cities with large Jewish communities, Antwerp is surrounded by a wire called “eruv” (Eiroew in Dutch).

The diaspora of Hasidim is a community based on strict observance of the religion, worship, observance of the laws, sabbath, study of the Thora, and ritual cleaning.

The community is led by a dynasty of famous rabbis and is strictly hierarchical. The family unit is led by the husband and is patriarchic in all household decision-making.

Contraception and marriage with a non-orthodox are not allowed which makes traditional families very large.

Hasidic women represent a unique face of Judaism. As Hasidim—ultra-Orthodox Jews belonging to sectarian communities, worshipping and working as followers of specific rebbes—women are set apart from assimilated, mainstream Jews.

The Hasidic ideal is to live a hallowed life in which even the most mundane action is sanctified. Hasidim lives in tightly knit communities (known as “courts”) that are spiritually centered around a dynastic leader known as a rebbe, who combines political and religious authority.

The cultural identity of the Hasidic culture in Antwerp (22,23,24)

In the USA New York Jews have a strong political lobby in politics or social organizations, but that is not the case In Belgium. In the melting pot of New York are different communities often opposite in social life and beliefs and is coexistence a difficult battle focusing on turf and race. So are the differences between the Hasidic culture and the Porto Ricans often a problem as the Jewish community is defending their turf and their race. Arranged marriages in the Hasidic community can only be with Hasidic religious partners.

The Hasidim in Antwerp is faced with a double dilemma to live his life in the culture of orthodox Jewry on the other hand to try to be integrated and assimilated with Belgian and European culture as can be seen in the picture below. (21,25)

“Faced with a European model that provides little place for strongly affirmed identities and that the recent demographic shifts have made stricter than ever, they have to make a life choice. They can subscribe to this model and become cultural Jews only. This will allow them full membership in European societies, but it comes at the cost of their own Jewishness. Indeed, as we have shown, an identity based solely on culture has little chance of being sustainable. By accepting the reduction of their Jewish identity to its cultural dimension, the integrated Jews, voluntarily or not, are willing to put it at risk for integration’s sake. They accept being not Jews, but Europeans”. Source: Jonathan Tobin’s article in Commentary “The end of European Jewry” and the in-depth study about European Jewry challenges: “European Jewry – Signals and Noise.”

Source: http://jewishecosystem.org/euro2010/, p.7.

Source: http://jewishecosystem.org/euro2010/, p.7.

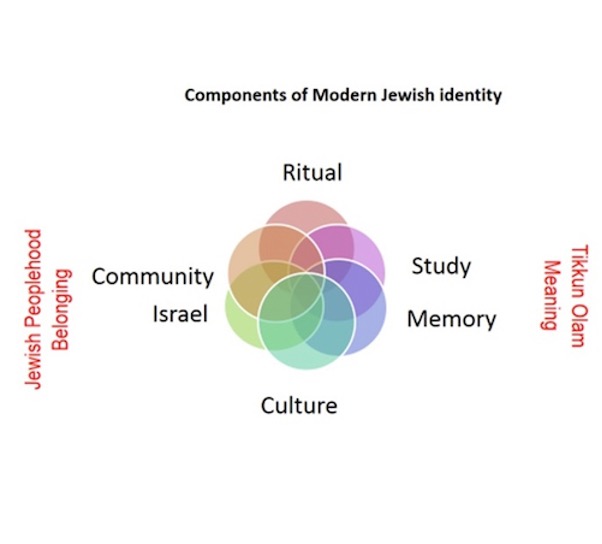

“The real question, therefore, concerns the possibility of an alternative model that will allow European Jews to remain proud and serious Jews while engaging towards a broader society. The need to build environments that will allow European Jews to “act Jewishly for non-Jewish causes” and follow the ancestral universal biblical commandment of TIKKUN OLAM (see figure)

Example of Israel’s cultural dimensions by Hofstede:

| Dimensions | indicators |

| Power distance | 13 |

| Individualism | 54 |

| masculinity | 47 |

| Uncertainty avoidance | 81 |

| Long term orientation | 38 |

| Indulgence | -1 |

Source: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool?countries=israel

Hasidim orthodox cultural values differ from Israel’s national values; there is a higher power distance (religious, hierarchy, patriarchism), masculinity is higher and long-term orientation is limited because of the strict observance of 161 rules.

Conclusions for the Hassidic community in Antwerp:

The Hasidic community can live and enjoy its cultural identity and is respected by the Belgian authorities and community. The main reason is the history of the Shoa in Belgium and the Netherlands (Anna Frank). Secondly, the freedom of religion and language are strong arguments in the Belgian context.

Some strict observation of the religious rules like the role of women and the fact that a man cannot touch the hand of another woman is seen in a “Woke” and feministic society as dated. However, this rule is also existing in Muslim traditions as well as the rule for women to be covered.

Cultural congruency and conformity

Hasidic communities are trying to conform to mimic cultural elements: individualism, risk-taking, and social values while respecting their cultural values in the extended familial environment. Cultural congruency with Belgian cultural values is not fully possible because of their religion. However, there is a need for adaptation by the host country and efforts are made on both sides to respect each other cultural identity.

As can be seen in the picture the cultural identity of Hasidim has many layers originating in religion, the long complex and dramatic history of the Jews in Europe and the dilemma of strong adaptation to a European context.

Cultural congruity: The finding of common ground between cultural values concerning differences and religious attitudes. This is the case in Antwerp, where organized consultations with the local authorities are a long-standing process and have proven successful.

Cultural assimilation or the process of groups of different heritages becoming part of the existing national cultural dimensions and acquiring basic habits, attitudes and modes of life of an embracing culture. This is partly the case as some attitudes and habits are prescribed by religious laws and also practiced in other religions.

Amalgamation is perhaps the word for the cultural process it refers to a blending of cultures, rather than acculturation. The blending of the two cultures is not possible for religious reasons.

Overall conclusions:

The picture of the mural Matonge shows the idea of the Congolese artist of how multiculturalism is seen in the Congolese part of Brussels. However, it does not show the cultural processes of the newcomer migrant in Belgium.

The two diasporas examined in this essay along the key words: congruency, conformity, amalgamation, adaptation, assimilation, transnationalism, and integration.

The Congolese community in Brussels has a transnational hybrid cultural identity that is multiscaled. The identity is based on the tribal, African cultural values with transnational adaptation to life in Belgium and Europe. This is facilitated by the Ubuntu Philosophy: “the dance of being We and the others.”

The Hasidim community is a different case, where cultural values are based on religion and strict religious laws. The Jewish culture based on identity, solely on religion and culture has little chance of being sustainable. “By accepting the reduction of their Jewish identity to its cultural dimension, the integrated Jews, voluntarily or not, are willing to put it at risk for integration’s sake. They accept being not Jews, but Europeans”. (3)

Bibliography:

- Abicht, Ludo (1995–96). “The Jerusalem of the West: Jews and Goyim in Antwerp”. The Low Countries – Arts and Society in Flanders and the Netherlands: A Yearbook: 21–26. Retrieved 9 May2023.

- Belcove-Shalin, Janet, Hasidism Today: Ethnographic Perspectives on Contemporary Hasidic Culture. New York, SUNY Press.1993

- JW Berry, JS Phinney, DL Sam, P Vedder;Immigration Youth, identify and adaptation; applied psychology; Wiley on line Library,2006

- Madly Simba Boumba; Participative Web 2.0- and Second-Generation Congolese Youth in Brussels: Social Network Sites, Self-Expression, and Cultural Identity; Diaspora and Media in Europe, 2018;ISBN : 978-3-319-65447-8

- The Encyclopedia of cross-cultural psychology; First published: 24 September 2013; Print ISBN: 9780470671269| Online ISBN: 9781118339893| DOI: 10.1002/9781118339893;Copyright © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

- S Demart; Congolese migration to Belgium and postcolonial perspectives:- African Diaspora, 2013 – brill.com

- D Garbin, M Godin; Saving the Congo’: transnational social fields and politics of home in the Congolese diaspora ;Africans on the Move, 2016 – api.taylorfrancis.com

- D Garbin;Regrounding the sacred: transnational religion, place making and the politics of diaspora among the Congolese in London and Atlanta;Global Networks, 2014 – Wiley Online Library

- Geert Hofstede, Gert Jan Hofstede, Michael Minkov (2010). “Cultures and Organizations, Software of the Mind”, Third Revised Edition, McGraw-Hill 2010, ISBN 0-07-166418-1. ©Geert Hofstede B.V.

- Khoza Reuel J; Attuned leadership, African Humanism as compass, Penguin Random House South Africa (Pty), 2012

- Leyendecker, B. (2011). Children from immigrant families—Adaptation, development, and resilience. Current trends in the study of migration in Europe. International Journal of Developmental Science, 5(1-2), 3–9;2011

- The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books, 1972, 205 pp., $6.50 (cloth) $2.75 (paper) L.C. 73-187907

- Malthus, Thomas Robert (1798). “VII”. An Essay on the Principle of Population.

- Portes, A., Guarnizo, L. E., & Landolt, P. (1999). The study of transnationalism: Pitfalls and promise of an emergent research field. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 217– 237. doi:1080/014198799329468

Journal of Social Development in Africa, 2015 – researchgate.net

- Oluwole Sophie Bosede; Socrates and Orunmila; Editions Ten Have;2017

- Eva Swyngedouw & Erik Swyngedouw(2009) The Congolese diaspora in Brussels and hybrid identity formation: multi-scalarity and diasporic citizenship, Urban Research & Practice, 2:1, 68-90, DOI: 1080/17535060902727074

- Peter F. Titzmann, Andrew J. Fuligni; Immigrants’ adaptation to different cultural settings: A contextual perspective on acculturation; Introduction for the special section on immigration;International Journal of Psychology; 10 November 2015

- Jonathan Tobin; Commentary“The end of European Jewry“ in European Jewry – Signals and Noise.”

- http://jewishecosystem.org/euro2010/, p.7.

- Geert Hofstede, Gert Jan Hofstede, Michael Minkov (2010). “Cultures and Organizations, Software of the Mind”, Third Revised Edition, McGraw-Hill 2010, ISBN 0-07-166418-1. ©Geert Hofstede B.V.

- Vanden Daelen, V. “Antwerp Jews and the Diamond Trade: Jews shaping Diamonds or Diamonds shaping Jews.” XIV International Economic History Congress in Helsinki, Finland. 2006.

- Rose-Carol Washton Long, Matthew Baigell, and Milly Heyd(ed); Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation; EW RESEARCH CENTERMAY 11, 2021;JEWISH AMERICANS IN 2020.

- Wursten H., (1997). ”Mental Images. The Influence of Culture on (Economic) Policy”Mental_images_The_influence_of_culture_on_economic_policy

- Zwaenepoel L; Development Management: An introduction to Moral Management in African Prismatic Societies, California University, USA, 1990

Bio Dr. Luc Zwaenepoel

He is a Drs in Development economics, PhD Development management and a Master’s in Family Sciences and Sexology. He lived and worked for 40 years on the African continent, the Indian Ocean and the Far East. His international work in economic development brought him in contact with a better understanding of African organizations and communities, with a great interest in the Bantu philosophy and the Ubuntu approach. He worked as a social demographer in the Institut de Formation et de Recherche Démographique (IFORD) and was a programme manager of the KFW/IGAD migration fund for the Horn of Africa.

As a novelist, he wrote a book: “Sartre in the Congo” 2020, a magical realism story, against the background of the first genocide in Kongo and Rwanda. Luc_zwaenepoel@hotmail.com

0 Comments