Cross-cultural psychology. Some observations

Huib Wursten, huibwursten@gmail.com

Summary

The author reflects on the question of why the accumulated empirical research on the influence of culture did not lead to the recognition that it is a very important factor in policy decisions.

Keywords:

Upwards sensitization, Downwards causation, Worldviews, Hofstede dimensions, Consciousness.

Introduction:

One big question still remains after my 34 years of consultancy in what I prefer to call “Intercultural Management” for Top Fortune companies and international organizations: why is this body of knowledge not taken more seriously by major policymakers?

Why is it that Governments seldomly invite experts in this field to explain how the values we identify play a decisive role in the way democracy is defined, in the set-up of societal institutions, in the content of important policies, like economic priority setting, taxing policies, immigration, welfare, etc.?

Why is it that in the very diverse European Union, ideas about how values influence leadership and decision-making are not reflected in conscious attempts to align the five systems we can identify?

While being involved by Top Fortune companies like IBM, Nike and JPMorgan Chase and international organizations like the EU, the IMF, the World Bank, UNDP, and the ECB, the question remains: why did the cultural interventions not lead to real change?

Looking back, some answers are possible as to why the accumulated knowledge in this field only sometimes gets the attention it deserves.

It starts already on the level of awareness training.

1. The definition of culture and the consequences.

In my work, I use the evidence-based framework created by Geert Hofstede.

The Hofstede definition of culture: Culture is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others.”(Hofstede Geert 2001; Hofstede et al. 2010)

The deepest layer of this preprogramming is “values,” defined as “the preference for one state of affairs over others.”

In this definition, value preferences result from subconscious and pre-programmed learning during the first 8-10 years of human life. After that period, the preferences are very difficult to change. For clarification, see two earlier articles describing the profound influence of this programming (Varkey, Kato, Wursten, 2022) and (Wursten, Jacobs, 2013)

This message is emotionally difficult for most highly educated managers in international organizations. The implicit message is:

“You think you are a rational person making conscious decisions about right and wrong. You think you can make a detached analysis of situations, asking for a decision. However, your decisions are “steered” by subconscious pre-programmed cultural preferences. “

It is a difficult message indeed. Some find this even insulting!

2. Underestimation of the depth of the research findings

Some people have the idea that this is just one of the many theories leading to advice about how to cope with diversity. This underestimates the importance of Hofstede’s findings. He had no preconceived ideas about the core values of diversity. He found these by applying factor analysis. Factor analysis (FA) is a technique to simplify a set of complex variables or items using statistical procedures to explore the underlying dimensions that explain the relationships between the multiple variables/items. So, in other words, the four confirmed Hofstede dimensions are about the core four issues all societies worldwide have to relate to.

Hofstede found four core issues. The different preferences of almost all nation-states in dealing with these issues have been charted. Because we are talking about fundamental value preferences, a discussion about diversity should necessarily start here.

What are the key issues?

Power Distance. How people deal with the unequal distribution of power in their society. In some countries, people accept hierarchy as an essential fact of life. In some other countries, people see hierarchy as just a matter of convenience in organizing a group or community.

IDV –The direction of loyalty. In collectivist cultures, people prioritize loyalty to the ‘ingroup’ they belong to (extended family, tribe, ethnic group, religious group, etc.). In contrast, in Individualistic cultures, people prioritize individual rights.

MAS –The direction of motivation: a preference for competition (masculine cultures) or a preference for cooperation and consensus-seeking (feminine cultures).

Uncertainty Avoidance -The need for predictability. The continuum goes from a strong need for predictability to a weak need for predictability.

For all dimensions, it is important to understand that we are discussing a continuum and not a binary division in comparing countries.

3. Overestimation of the ability to be Open-minded. “I am a Citizen of the world”.

Some resist cultural awareness programs because they think they are above the subconscious influence. They say to everybody that they are citizens of the world and have no specific preferences.

This is reason to be doubtful about this claim. Evidence shows that because of the pre-programming, it is, in reality, difficult to stay open-minded working in an international environment.

Given an opportunity to work internationally, most people are initially motivated to be open-minded and to learn from other perspectives and make it work. They are eager to meet interesting new colleagues with different approaches to problems. After a while, however, irritation starts growing if the “others” have solutions that go against the pre-programmed preferences. Research indicates that the initial open-mindedness turns into a heightened emphasis on the preferred behavior. What was first sub-conscious is becoming a conscious preference due to the confrontation. This means that, for example, concerning leadership Americans abroad behave more American than Americans in the USA. The same tendency applies to all cultures in reality. (Wursten 2021)

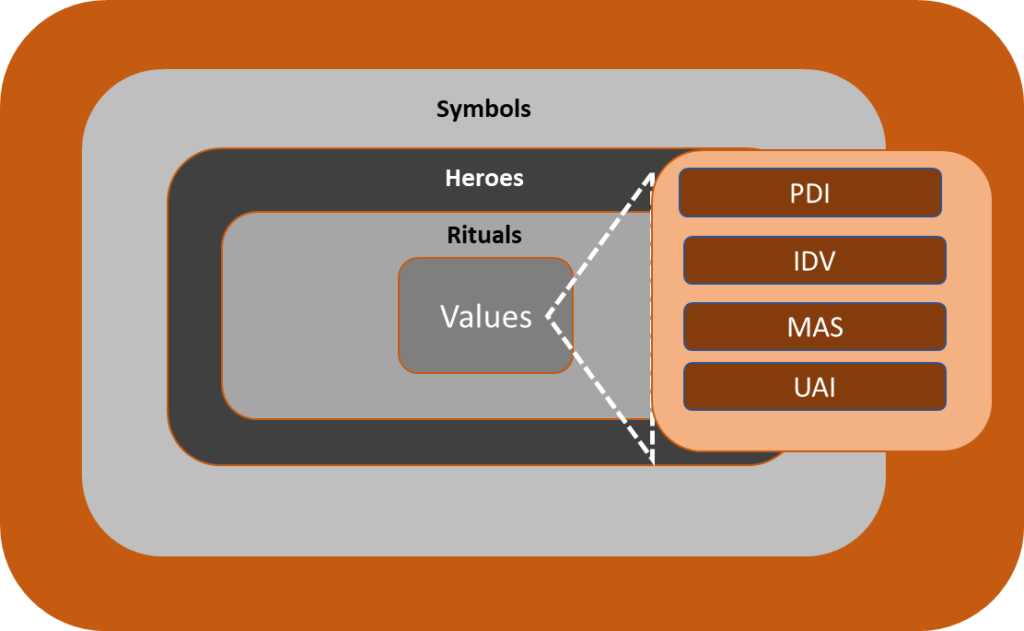

4. Lack of awareness of what can be changed. Values, Rituals, Heroes and Symbols

Culture has different layers. In the representation below, the layers are ranked from superficial to critical. From visible aspects subject to change to invisible but essential “values” that are deeply ingrained and difficult to change.

Because of the reluctance to take the pre-programming seriously, the cultural issue tends to be brought back to the more visible behavioral aspects: Symbols, Heroes and Rituals. In short, what is called organizational culture. The belief is that this ” corporate culture.” can define “Shared values”. HQ is then defining the norms. Others are asked to adapt to the norms. Even stronger, it might lead to a recruitment practice where only these people who know how to behave according to the criteria of HQ are hired. “Cultural cloning” is the result. This leads mostly to a mono-cultural approach.

5. Lack of understanding that “Upward sensitization” needs to be combined with the notion that culture has a “Gravitational influence” on important societal and organizational choices—”Downward causation”.

a. Upwards sensitization: Making people aware of their programming.

The culture in the workplace Questionnaire is a tested approach, endorsed by Prof. Geert Hofstede. Using the Questionnaire is making people aware that:

- They are also programmed concerning preferences. They are not neutral or above the programming.

- The country scores are central tendencies of a bell curve. As an individual, your private scores might be different.

- This explains possible irritations you have about the standard behavior of your compatriots.

- The bell curves in other countries have another shape.

The second step is to make people aware of:

b. Downwards causation

Combining the scores on the 4 Hofstede dimensions leads to a Gestalt (the whole is more than the sum of parts). This Gestalt creates a worldview. This worldview has a “gravitational” effect on all levels of behavior. In other words, the of behavior is derived from the preferences of the worldview. For example, the meaning and significance of the roles people have as parents, consumers, customers, employees, etc. Also leadership styles, delegation patterns, control mechanisms, and communication styles are to be understood by the preferences of the Worldview people have. See for a deeper analysis: https://culture-impact.net/identity-and-the-gravitational-influence-of-national-culture/. (Wursten 2019)

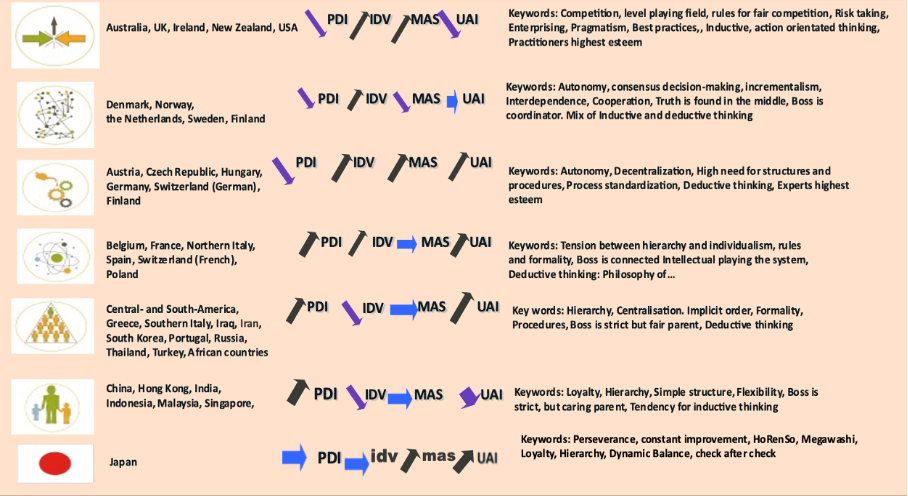

6. The Seven Worldviews

Seven consistent worldviews can be identified: The Contest, The Network, The Well Oiled Machine, The Solar System, The Human Pyramid, The Family, and (standing alone) Japan.

See for an overview of the attributes: Culture and Worldviews.

6.1 The worldviews define the “rules of the game.”

The worldviews shape the preferred “rules of the game”.

It is essential to understand that more is needed to be aware of different game rules. It is wrong to assume that it is just a matter of choice, like choosing which rules apply in playing cards. Different value systems have different rules of the game!

6.2 The pre-programmed Value preferences load the rules of the game.

For example, leadership and management techniques are not neutral and can be applied everywhere. MBO and Quality circles require a certain Worldview.

6.3 Majority preferences and minorities

Majority preferences shape the worldviews and the consequent rules of the game. Minority preferences exist.

However, the majority formulates the criteria for what is seen as successful and what is not. To be effective, the ones with alternative preferences learn the hard way to adapt to the required behavior for getting things done.

This means that minorities, over time, develop the skills to cope with the majority criteria. If they are asked to operate in another culture that mirrors their profile, they need more practical skills and competencies to perform successfully.

Of course, some people always refuse to behave according to the majority culture. The behavior we are talking about is about “most people most of the time.”

However, because of the homogenizing influence of the majority preferences, it is no surprise that the observations about friction between nationalities that are supposed to cooperate in international organizations are very consistent. Whatever type of industry, service, or product, the downward causation is at work and leads to different majority rules of the game. In cooperating, the differences become manifest. In this sense, it is counterproductive to call this observation just stereotyping. Stereotyping is assuming behavior that is not shown in reality. The majority preferences are however real and consistent. However, only sometimes a hundred percent. The 80/20 rule can be applied. The predictions apply in 80 % of the cases. It is wise always to check if the people concerned recognize the assessment.

Solutions for friction can never be found in forcing people to adopt another majority system. Real solutions can be found by comparing the rules of the game and developing win-win approaches that don’t go against the preferences but cover the existing ones. This requires creative negotiating skills.

Both approaches, upward sensitization, and downward causation are needed for effective change management.

7. In diversity programs, the gravitational influence of the rules of the game is underestimated

Nowadays, there is a lot of interest in Diversity programs.

Content-wise, these programs range from: “all people are unique” to “under the skin, everybody is the same.”

The messages about the need to cope with the “diversity” subject range from:

We need to celebrate diversity. It makes teams more creative and innovative. Differences become strengths in a collaborative effort. Collaboration is a path to peace.

to

The survival of mankind will depend to a large extent on the ability of people who think differently to act together”. (Hofstede 2010)

Celebrating Diversity: The Uniqueness of Individuals

One of the most memorable radio programs I remember from the recent past was produced by sending an aerial work platform to random building blocks, lifting a reporter to a random floor, followed by a knock on the window, and starting an interview with the one opening the window.

It was a simple concept with amazing results because the interviews were always very interesting. The conclusion was that each life has a unique story interesting enough to attract a big audience. The reporter remarked that:

Each life story deserves a book!

Understanding individual Diversity is interesting and fun at the three visible levels. It is great to look at the Art of other cultures—the paintings, music and dance. Rituals attract millions of people. It is great to visit Ireland to celebrate St . Patrick’s Day. It is amazing to experience Diwali in India.

It is self-evident that in creating teams, individuals’ special talents and skills should be considered. In any sports team, you need a mix of talents. In football, it is unthinkable to have only strikers. Also, defenders and passers are required to make the team effective.

This is relatively easy within one worldview with a common understanding of the cultural rules of the game. It is much more difficult if people need to work together in an international team with different worldviews. It is even more difficult if teams from different worldviews need to cooperate across borders.

7.1 Diversity within a worldview

Comparisons are always dangerous. However, in discussing diversity within worldviews, it can best be compared with style and dialect within the grammar of a language system.

In every language, there is a shared grammar system. The correct use of the grammar system is taught in schools, and tests and exams ensure that the grammar system survives for the next generation. But in all countries, one can find differences in style and dialects. Nobody will deny that the basic grammar systems of English, Chinese, Russian, and Sanskrit are different. People sharing one basic grammar system can still differ in style and dialect. With sometimes strong consequences. Take the example of the Scottish and the English. They share the same basic grammar system. Still, the Scottish are so different in style and dialect that even the English need help to understand what they say. This is how to look at diversity and most regional cultural differences. In almost all countries, people share a homogeneous (majority) culture, the Worldview. But rituals, heroes, and symbols, the more superficial layers of the culture, can be different.

People born and living in a certain culture see the basic grammar system and the worldview of that culture as self-evident and normal.

Deviation from the standard attracts attention and can be experienced as an emotional breach in expected behavior. For the people concerned, it can be seen as an argument that “culture is changing”. However, defining their behavior as the norm would be a mistake. They stand out just because they do not behave according to the norm. The different behavior gets a lot of (media) attention. Just because it is so different

Two examples:

a. A former Dutch colleague is in a care center after a stroke. There are about 20 nurses. Seventeen of them behave according to the expectations of the Dutch culture. They respect the patients’ autonomy as much as possible and involve them in decision-making. Three nurses are top-down in their behavior and don’t show patience in involving the patients. Observation of the colleague: all discussions among patients are about the behavior of these three because they are perceived as authoritarian.

b. Going back in time in the USA, the “Iron John” groups in California got a lot of media coverage. The base was a book by Robert Bly: Iron John. A book About Men. It inspired a men’s movement in the early 1990s. The book was 62 weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list. Groups formed with therapeutic workshops and wilderness retreats, often performing Native American rituals such as drumming, chanting, and sweat lodges. These rituals were organized to facilitate the personal growth of participants (most often middle-class middle-aged males) to connect spiritually with a lost, deep masculine identity or inner self. At that time, it was seen by some as a sign that the culture was changing.

In the meantime, it is clear that such a development did not change the dominant culture. It is getting attention because it is different from the dominant culture and should be understood as a counter-culture.

7.2 Culture and Identity

The effects of worldviews on Individuals are clearest when looking at one of the Hofstede dimensions, Individualism versus Collectivism.

In Collectivist cultures, people derive their identity from group membership. In Individualistic cultures, people create identity by focusing on uniqueness. See: https://culture-impact.net/identity-and-the-gravitational-influence-of-national-culture/

8. The world is too dynamic for cultural explanations.

A frequent remark made by customers is that cultural explanations are too static in a rapidly changing world.

The answer is that Culture is consistent but not static. The development of new behavior is, in a consistent way, influenced by the set of preprogrammed collective preferences.

Societies are indeed constantly developing. Two acronyms are used to describe this:

BANI is an acronym comprising the words ‘brittle,’ ‘anxious,’ ‘nonlinear,’ and ‘incomprehensible.’ The concept is attributed to Jamais Cascio, a California professor, anthropologist, author, and futurist. Cascio has written several publications on the future of human evolution, education in the information age, and emerging technologies.

VUCA stands for Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity and was created by the United States Army War College in the late 1980s to describe the scenario of the post-Cold War world.

Many people feel that “the only constant is change.” they say: “I am very different from my parents, and my grandparents are very different from my parents.” How can you apply findings from research 40 years ago to this rapidly changing environment?

The explanation is that usually, the visible aspects of culture are compared. In so doing, it is easy to observe that the observable behavior of the present generation differs from that of past generations.

Saying that culture is consistent does not imply that culture is static. Our parents and grandparents behaved differently because they lived in totally different conditions. Who had to deal with issues such as Globalization, the European Union, the Internet, mobile telephones, algorithms, Artificial Intelligence, etc., fifty years ago? The world is changing rapidly, and we are being forced to adjust to these changes and to develop new behavior. However, the development of this new behavior is not the same shape everywhere and is certainly not “random. The required new behavior is, in a consistent way, influenced by the set of preprogrammed collective preferences.

8.1 The consistency of Hofstede’s framework over time.

After the first publication of Hofstede’s research findings in Cultural Consequences, several people tried rightly to falsify the results.

A meta-analysis of such attempts showed that the results survived the scrutiny.

The latest repeat research was carried out by Sjoerd Beugelsdijk, a Professor at the Groningen University, and his team. They were looking at the continued validity of Hofstede’s (2001) framework and whether the relative positions of countries on national culture dimensions have changed over time.

Their results indicate that they have not. Correlations between countries’ dimension scores of the two generational cohorts they studied are remarkably close.

But on two dimensions, a slow change was detected. Everywhere, the score on PDI tends to be lower. Everywhere, the score for Individualism tends to be higher.

This finding means that, although cultural change has occurred, it has happened similarly for all societies, leaving countries’ relative positions largely unaffected.

8.2 Institutions and the need for change

Looking at how societies organize themselves, the majority preferences have a modifying influence at both micro and macro levels. They influence how good leadership is defined, how the decision-making process is structured, and how people monitor how policies are implemented. In short, everything that has to do with organizational behavior.

The preferred rules influence patterns of thinking, which are reflected in the meaning people give to the different aspects of their lives and, therefore, help shape the institutions of a society.

The Institutions cope with the force fields around them with a set of solutions that are relevant for a time. However, because of the rapid societal changes, the solutions tend to be frozen after a time and need to be more adequate in coping with new challenges. New policies are formulated to cope with the new reality. The relevant thing is that the new guidelines are not random or the same in all societies.

What should be more transparent is that the new policies are derived from the worldviews and the preferred rules of the game.

9. Imagined and True realities.

If one compares official organizational charts of organizations worldwide, they look the same everywhere. The same is true about all other relevant issues for today’s global business players: strategies, HRM systems, including reward techniques, management approaches like MBO, appraisal instruments like 360-degree feedback systems, etc.

Seemingly, the organizations are steered in the same way. In MBA programs everywhere, the same theories are taught; the general feeling is that organizational behavior is culture-neutral.

These theories reveal that most management, marketing, economy handbooks, etc., come from Anglo-Saxon countries: the USA, Canada, and the UK. The students from MBA programs assume that what they are reading about is just the latest development, the latest description of best practices. After graduating, they try to implement these best practices in organizations in their countries. If, then, after a time, they discover it’s not successful, they blame the failure on the people involved. Accusing them of being resistant, backward, stubborn, and ignorant. They don’t realize that the promoted theories are not wrong but have a value context that fits the rule of the Worldview of the Anglo-Saxon culture group, but not necessarily the rules of the game of the six other worldviews.

This is not something that is to blame on the Management Gurus. Frequently, I heard these “Gurus” say: “You tell me that this is not possible in your country. Tell me then, please, about the theories and research from your culture”. Then, most of the time, there is silence. The Non-Contest cultures should do much more to make the values and realities in their own cultures more explicit. They should be more aware that there is a difference between the “Imagined reality” (assuming, for instance, that what is valid in the USA is also valid everywhere) is different from “True reality”.

Conclusions:

To have the impact it deserves, interventions making use of the accumulated knowledge about the influence of culture should:

- Combine Upward sensitization and Downward causation

- Take the following steps in action planning:

1. Create an understanding of what constitutes basic value diversity worldwide.

2. Create an understanding of the seven rules of the game that distinguish countries worldwide.

3. For aligning people, the next step is deciding which of the 28 organizational consequences that are distinguished are getting priority in the change (usually a maximum of 4: decision-making, leadership, delegation, and control). Tool: list of 23 comparisons (Wursten 2019)

4. Negotiate mutually accepted rules of the game. Inclusive solutions can be implemented?

Literature:

Beugelsdijk, S., Maseland, R. and van Hoorn, A. (2015), Are Scores on Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture Stable over Time? A Cohort Analysis. Global

Strategy Journal, 5: 223–240. doi: 10.1002/gsj.1098

De Mooij, M. “The future is predictable for international marketers: converging incomes lead to diverging consumer behavior” International. Marketing Review. Vol. 17 No. 2, 2000, pp. 103-113 (University Press)

Hofstede Geert: Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd Edition. 596 pages. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications, 2001, hardcover, ISBN 0-8039-7323-3; 2003, paperback, ISBN 0-8039-7324-1.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the.Mind. Berkeley: McGraw-Hill

Malik Ken (2023) Focusing on diversity means we miss the big picture. It’s class that shapes our lives. The Observer January 29, 2023

Minkov, M. & Hofstede, G. (2014). Nations versus Religions: Which Has a Stronger Effect on Societal Values? Management Int Rev, 54, 801. doi:10.1007/s11575-014-0205-8

Søndergaard, M. (1994) Hofstede’s consequences: a study of reviews, citations and replications.Organization Studies, 15, 447-456

Taylor, Charles, The Politics of Recognition, In Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Edited by Amy Gutmann. Princeton: Princeton UniversityPress, 1994, 25-73

Varkey, Kato, Wursten (2022) Educational practices and culture shock. Culture Impact Journal. Special Culture and Education (2022). https://www.academia.edu/92272929/

Wursten Huib (2019). The 7 Mental Images of National Culture Leading and Managing in a globalized world ISBN-10: 1687633347 ISBN-13: 978-1687633347

Wursten, Jacobs (2013) The impact of culture on education Can we introduce best practices in education across countries? https://www.academia.edu/22731263/

Wursten, H: Reflections on Culture, Art and Artists in Contemporary Society. In JIME, July 2021

Wursten H, Lanzer F. The EU: The third great European cultural contribution to the World. 2015.

0 Comments