The Bani World And Nation-Building

Using coaching and intercultural competence at international organizations in the context of BANI and Nation-Building

Thomas Anthony Imfeld, M.A., Managing Director, bullseye international GmbH, Trier, Germany

Synopsis/Abstract

In a BANI world characterized as brittle, anxious, nonlinear, and incomprehensible, leaders in international organizations, impacting nation-building, benefit from having intercultural competence when using coaching approaches. This article focuses on what is useful to understand and apply in the context of cross-cultural coaching. Models are introduced to add insight for fostering performance. The paper fuses 3 components: the BANI model; the coaching model; intercultural model.

Keywords

Coaching, BANI, managing behavioral complexity, national culture, change

Implications

- Nation-building involves change and the development of people, societies, and their institutions. Human beings are a critical component in these processes. Working with intercultural competence and empowerment through coaching, coach and coachees support individual and organizational development objectives.

- Resilience, adaptability, empathy, mindfulness, and intuition are needed to cope and thrive in the face of BANI. Leaders in international organizations support the development of corresponding mindsets and behaviors at both the individual and group levels by investing in people; this can be supported with coaching.

- Attitudes and behaviors to organizational and personal goals can be impacted by national culture. In this regard, it is useful for coaches to have intercultural competence.

- Motivation and communication are two illustrative areas highlighting the importance of intercultural competence that coaches and coachees use to focus on changing behaviors and seeking productive outcomes. Ignorance of cultural components is not an option for international organizations.

- Intercultural competence can be gained in various ways. For coaches in complex organizational settings, Hofstede’s 6-D Model and Huib Wursten’s Mental Images are constructs to effectively frame intercultural issues. In international organizations, with a myriad of nationalities, it is useful to access a model and a gestalt for reducing cultural complexity and facilitating hypothesis testing to foster informed actions.

Conclusion

In the juxtaposition of BANI and nation-building, international organizations underpin their own objectives when people are supported to understand and develop desired traits and behaviors. This is challenging. The personalized nature of coaching, in an environment of psychological safety, can have a significant impact on shifting attitudes and fostering concrete behaviors. Coaching can be used to reconcile and align individual development with organizational objectives. Working internationally means working interculturally. Change initiatives are supported by the action-oriented work and positivistic professional relationships between coaches and coachees. Empathetic, proactive, introspective human actors are paramount to supporting desired individual and organizational outcomes.

What is nation-building? Nation-building is a process of socio-political development that turns loosely or even contentiously connected communities into a common society with a state that corresponds to it. This article looks at the people in organizations that shape, accompany, and influence the nation-building process. These are international organizations such as the IMF, World Bank, UNICEF, NGOs, and multinational companies. What the nation-building process and international organizations have in common are human beings with a diverse range of personalities, behaviors, and national cultures who work with processes involving change.

Human actors in change processes operate in the context of BANI. More than ever, working internationally in a BANI world, people are pivotal components in change processes. Change initiatives can be effectively supported by coaching. In turn, coaching in international settings benefits from intercultural competence.

Organizations, nations, and individuals want to ensure survival. In this chaotic world, we have great uncertainty about what is to come. Long-term plans and strategies are becoming less and less reliable. The fast pace of change and chaos makes some ideas that seemed illogical just months ago and were not part of any planning suddenly worth examining or even implementing. In the BANI environment, we learn that nothing is right and nothing is forever. Some say, what matters is to get through the storm and do it fast.

BANI is an acronym made up of the words ‘brittle’, ‘anxious’, ‘nonlinear’, and ‘incomprehensible’. The concept is attributed to Jamais Cascio, a California professor, anthropologist, author, and futurist. Cascio has written several publications on the future of human evolution, education in the information age, and emerging technologies. In our world with high levels of chaos, the well-known concept of VUCA is less relevant. VUCA stands for Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity and was created by the United States Army War College in the late 1980s to describe the scenario of the post-Cold War world. To replace VUCA, “Facing the Age of Chaos” with BANI at its core, Jamais Cascio publishes his article. Let’s examine BANI word by word.[1]

Brittle: In the BANI world, a system can work well on the surface, even if it’s on the verge of collapse. Consequently, taking precautions not to rely completely on the assumptions behind any systems makes sense, even if we think that the systems appear reliable, flexible, and unbreakable. To illustrate this, just think about the fragility of markets, our environment, peace, and the human condition. If something is brittle or fragile, we, as human beings can show capacity and resilience.

Anxious: While information is essential, too much of it creates anxiety. Even, technologies can contribute to making people feel powerless and unable to make important choices in times of pressure and tension. Our networked, virtual and digital world has so much information, threats and fake news that it easily becomes overwhelming. That’s why mindsets enabling us to take some distance from situations and develop creative problem-solving solutions are pivotal. Using emotional intelligence and cultural intelligence can also give us an edge when facing anxiety. When we feel anxious as human beings, we can apply empathy and mindfulness.

Nonlinear: In the BANI world, cause and effect are no longer sufficient for understanding, coping with, or mastering phenomena. We are increasingly facing non-linear paths and it’s sometimes disconcerting. We’re frustrated by our attempts at planning, especially long-term. We are experiencing accelerated economic crises, environmental threats, pandemic outbreaks, and wars. Technology is developing at a break-neck pace. Leaders are using artificial intelligence, machine learning, and algorithms to make sense of things and master decision-making. This implies that being able to flexibly deal with various scenarios and implications is the order of the day. If something is non-linear, as human beings, we seek context and adaptability.

Incomprehensible: Living in a fragile, anxious, and non-linear world makes many of the events, causes, and decisions incomprehensible. As human beings, we’re pretty good at finding answers but it is harder when many pieces of a puzzle are concurrently in flux, due to the fast pace of changes. Even having more information doesn’t help us unless we can make meaning out of the information. Binary thinking is inadequate. Either vs. or is not enough. Instead, finding meaning, purpose and direction require “and” thinking[2] added to the ability to prioritize. Technology is used to make sense of this complexity. This includes artificial intelligence, machine learning, and deep learning. If something is Incomprehensible, humans seek transparency and intuition.

While the BANI scenario can appear foreboding, it holds opportunities for persons and organizations willing to grow, learn and embrace change. It is possible to become anxious, paralyzed, apathetic, or even depressed when confronting BANI. Alternatively, we can grow personally, with cohorts and collaborators using insights for change and leadership. Are nations, organizations, and individuals willing to learn and grow by preparing for and coping with BANI? Many leaders are ready. This article is dedicated especially to innovators and early adapters.

In the context of BANI, coaching emerges at the crossroads of nation-building, international organization, and individual development. Coaching is centered on performance-based psychological principles. Coaching is about evoking solutions and supporting their implementation. Equally important in coaching is understanding and learning about a situation, an environment, a setting from different perspectives, and weighing alternatives for making sound choices and decisions. The purpose of coaching is to allow a coachee to understand their thinking and activate resources to achieve something worthwhile for the coachee, and often, their organization.

Coaching as a process enables learning and development to occur and performance and potential to improve. A coach uses knowledge and understanding of the process as well as a variety of styles, skills, and techniques that are appropriate to the context in which the coaching takes place. Field experience contributes to a coach’s value-added as does having specialized knowledge and subject expertise. A coach helps coachees learn how to act and behave during specific situations in the workplace.[3] In a coaching process, a key is to let coachees be learners, rather than a coach imposing ways of facing situations. Instead of “telling” coachees how to do things, coaches empower coachees to make future decisions on this own.

The coaching starting point is positivistic. It is about a person’s potential, not just their performance. The foundation to this way of thinking and interacting is trust. With trust, the coach positively influences performance. Coaching is a commonly used method of employee development that generates positive business outcomes. A strong coaching culture has been linked to increased business performance and employee engagement.[4] In organizations, coaching is typically used in five areas: 1) improving team functioning; 2) increasing engagement; 3) increasing productivity; 4) improving employee relations, and 5) speeding up leadership development.

Ultimately, coaching is related to being Agile. When companies start an Agile transformation -i.e. seeking more innovation in a rapidly changing technological world- and people learn new ways of working including self-organizing teams, the quest is really for changing mindsets. Yet, the reality is that not everyone has an Agile mindset or values. The point is that an individual’s personal value structure does not equal behavior. All people can behave in Agile ways if they are motivated enough.[5] In this vein, coaching is supportive.

At the core of effective coaching is supporting the coachee to be more the person they want to be. Within organizational contexts coaching is about supporting behavioral change. Ultimately, coaching is about consciously and genuinely helping an individual align their behavior with their beliefs and values. We all have preferences and deep feelings for these beliefs and values shaped by our upbringing. In comparative terms, we can pinpoint both differences and similarities in these preferences when examining our relationship to power, the group, uncertainty, time, happiness, and sources of motivation. Let’s examine some differences between a coaching focus and an intercultural context.

From ancient Chinese philosophy, yin and yang are a concept that describes how contrary forces may actually be complementary, interconnected, and interdependent and how they may interrelate with one another.[6] This is a starting point to both distinguish and relate coaching and culture. For successful coaching across cultures, we seek to bring both aspects together.

| COACHING “I”

Coaching largely frames the individual as the focus of work. The idea is to support the individual to impact, change and develop her/himself directly and effectively. Shorthand: Me; I can change myself. |

|

CULTURE “WE”

Culture is a group phenomenon. Simply stated, culture is the shared values, ideas, customs, and social behavior of a particular people or society. Shorthand: How I fit into the We. |

Figure 1: Coaching and Culture

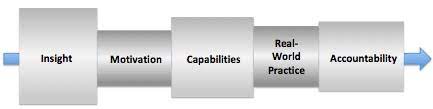

Seemingly countless tools and methods are available in coaching to support individuals to change their behavior. It can take anywhere from 18 to 254 days for a person to form a new habit and an average of 66 days for a new behavior to become automatic.[7] The emphasis here is on changing her/his own behavior and not the behavior of others. For the purpose of this article, we use David Peterson’s Development Pipeline. It describes the five necessary and sufficient conditions for change and is a useful guide with respect to where coaching provides the greatest value for the individual.[8]

Figure 2: David Peterson’s Development Pipeline

The pipeline analogy alludes to liquids traveling in a pipeline that can become blocked, slowed, or accelerated. In coaching, where understanding and goal attainment are critical parameters, it makes sense to focus on those areas where development is constrained. For example, if a coachee already has sufficient understanding about what they want to focus on if they want to focus, i.e., getting promoted, insight is likely not the focus condition. On the other hand, understanding their motivations might be useful, if serious conflicts or trade-offs need to be considered. Let’s look at each of the conditions by way of questions.

- Insight. Does the person understand what areas need o the developed in order to be more effective?

- Motivation. To what degree is the person willing to invest time and energy to develop her/himself?

- Capabilities. To what extent does the person have the skills and knowledge needed?

- Real-world practice. What opportunities does the person have to try out new skills at work?

- Accountability. What internal and external mechanisms exist for paying attention to change and providing meaningful consequences?

Each condition can be influenced by culture. To illustrate what this means, we’ll use the context of a coachee socialized in Central Asia i.e., Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkmenistan.

When we talk about issues related to culture, we are dealing with generalizations and bell curves i.e., the 80/20 rule, to provide a reasonable hypothesis that is subject to on-the-ground testing and always subject to revision. Sometimes issues have no cultural component, and instead, have to do with a particular situation and circumstance or are in the domain of individual personality factors. What is worth understanding when it comes to national culture and coaching? Let’s examine this using the five pipeline conditions.

Using the scenario of the Central Asian Coachee, Insight may be less guided by self-reflection of personal insights and more about understanding and guiding the perception of others and impression management. If this is so, the roots can be cultural. For example, it can be normal to frame issues in Islamic terms in which there is no or low separation between the religious, the personal, the leadership, and the government. In that case, using the Quran can be useful for framing issues for both coach and coachee. Another cultural factor is the importance of impression management and maintaining status. Where impression management is critical, awareness is necessary when attempting to use 360-degree feedback questionnaires or stakeholder interviews. Coaches need to be aware of the increased power perceptions and think about how any collected feedback is to be presented. Moreover, sensitivity to pride issues can cause the coachee to perceive negative feedback as an attempt to threaten career aspirations and goals. In the worst case, the source may be viewed as a foe. As a result, the coach will want to be aware of these factors, perform mitigation and seek constructive framing for all parties involved.

For Central Asian coachees, coaches want to pay attention to this mindset, framing, and make adjustments. Concretely, in goal setting, this can mean less emphasis on gaining personal insight leading to change and more about comprehending and channeling a response to the perceptions of others. The coach’s goal in developing insight is to support the individual to articulate what perceptions they want to change and how perceptions are limiting their ability to achieve their goals. In this vein, related questions can include the following: Whose perceptions matter to you, to your future, to your success?; Whom do you trust?; Whose perceptions do you believe?; Who knows you well enough that they can answer the questions posed?

In Central Asia, the coach is seen as an expert, often as a leader. As such, the coachee may not have the answers to these questions. In such cases, generic rephrasing may help as follows. What makes Yalda most effective in her role and her leadership? What gets in the way of Yalda being as effective as she is capable of being? What suggestions do you have for Yalda’s development? What skills, changes or development would make her more effective or help her to reach her potential? A coach can maintain a strong professional relationship with the coachees by paying careful attention to coachees’ sensibilities about any focus on weakness and understanding the importance of impression management.

In the second part of the development pipeline, looking at motivation, we can inspire commitment to change. Here motivation and trust are coupled. The coach can develop trust by using the GAPS model. This looks at Goals, Abilities, Perceptions, and Success factors from two perspectives. One perspective is the coachee’s view. The second perspective is viewed by other significant stakeholders. The model is useful because it can expose perceptional differences as a step toward implementing changes. Discussing goals and values can help in finding what is most meaningful for the coachee. This in turn can expose links to development priorities that can have a high payoff for both the coachee and the organization. With coachees from Central Asia, it can be useful to pay careful attention to high-status needs and social constructs, as forces for change. For example, motivation can be leveraged by showcasing a high-status person as supportive of the coachee’s goals for development and by keeping the sources informed of change and development.

Another cultural aspect is the external focus on control which can lead to the view that coaching is something that is done to someone and not done by the person/himself. In this mindset, the responsibility for change is on the couch and not the coachee. Here, the person may feel developed even if the actual change is less relevant. For the coach, awareness of these possibilities is useful.

When the liquid passes through the insight and motivation conditions of the pipeline we arrive at capabilities and real-world practice. This is all about having the skills and knowledge needed to effectuate change. Talking is not the same as doing. Here we may notice that Central Asians enjoy dialogue and are gifted talkers. Yet this is insufficient when it comes to change. For a change, we need to distinguish between insight/discussion and the demonstrated ability to do something different than it has been done previously. Coaches can work on building skills in real-time, through practicing and role-playing. This is followed by real work practice at work. High context and low context cultural differences may require techniques to understand how behaviors and emotions are communicated. Building trust and partnership are key. Finding the appropriate level of risk-taking for experimenting is a fundamental part of the process. This level will differ between in-coaching and outside-of-coaching environments, especially because of high impression and status management. Additional cultural factors to consider are saving face and obtaining the acknowledgment of change from those of high status. These two factors can make change real and meaningful to the coachee.

When the liquid gets near the end of the pipeline, we are in the condition of accountability. In Central Asian contexts, a lower internal focus of control lessens holding oneself accountable. However, the external focus allows for influence to come from respected external sources such as senior managers or important family members. In an organizational setting, this can be linked to measurable outcomes in the form or learning or coaching plans and specific measurable targets that are endorsed by the appropriate hierarchical levels. If the mindset is more about fixing problems rather than shaping the future, it is possible to use a senior person to achieve this. Working towards a clear commitment to action is the necessary criteria for change useful. This is supported by practice and role-playing as mentioned earlier.

Now that the liquid has reached the end of the pipeline, what have we learned? To keep the liquid flowing, coaches use psychology-based processes, real-world experience, and cultural understanding. In Central Asian cultures, changing behavior is more a social construct than and personal one. This is the “We” side of yin/wang that we saw at the inception of this article. In the coaching environment, safe opportunities to practice are a real value-added. Coaches find out where the energy is and channel it by creating clear links to measurable goals and conscious choices.

Coaches support their coachees and their international organizations to change and take action. In international settings, this is facilitated by having cultural competence. Methods, models, and approaches abound. Learning by doing is one approach. Taking courses and getting certification is another approach. Alternatively, people participate in online learning and videos. Another possibility is reading books. Whatever approach, you will want to consider a few things. Is your focus on country-specific cultural information? How much breadth and depth of knowledge do you seek? Are comparativist models, to speed your learning and provide you with linkages between cultural phenomena, of value to your objectives?

If you chose a single country approach, you have many possibilities. In one such approach culture is interpreted as a set of standards and you learn the ins and outs of a particular culture, by one nation or region at a time. This can be rewarding and time-consuming.

An alternative is to learn a cultural model. Cultural models abound yet the most scientifically validated cultural model is based on the research of Professor Geert Hofstede.[9] The result is a model comparing national cultures along 6 main dimensions. We will highlight the model briefly to understand its applications. Once a user comprehends what the six dimensions mean, it is possible to compare over 100 countries with ease and consider associated implications. This facilitates cultural hypothesis making and testing.

Hofstede defines culture as the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others. He acknowledges three levels in mental programming, i.e., personality, culture, and human nature. Seen as a pyramid, the base of human nature is inherited and universal. The next level is a culture which is specific to a group or category and is always learning. At, the peak of the pyramid is the personality which is specific to an individual and is both inherited and learned. When we work with culture, there are several layers, similar to the rings of an onion. At the core, where culture is deepest and associated with what is good/bad or right/wrong is values. Many people are not explicitly aware of their own values, let alone the values of others. It is understandable since culture cannot be easily seen or described. The outer layers of culture are easier to see and understand. These include rituals, heroes, and symbols. Also referred to as practices, these three outer levels of culture are what organizations tend to focus on and develop.

National culture and organizational culture are related but distinct. In this short article, the focus is on national culture also referred to as geographic culture, a concept delimited by national borders.

The 6D model of Hofstede works on a scale from 0 to 100 and makes tendencies in society more transparent and understandable. The cultural dimensions represent independent preferences for one state of affairs over others that distinguish societies (not individuals) from each other. In comparison to each other, the 6D score unlocks useful insights into intercultural human relations. For coaching in international organizations, the dimensions help to frame and contextualize intercultural issues.

A brief tour of the dimensions provides a taste of how this is done. The first dimension examines the extent to which the less powerful members of a society accept that power is distributed unequally. A low country score reveals that a bell curve member of a corresponding society will prefer low dependence, minimizing inequality and hierarchy for convenience. By contrast, a high score reveals a bell curve preference for high dependence, inequality is accepted and hierarchy is seen as needed. Numerous correlations reveal rich details of societal preferences. In our Central Asia example this dimension is revealed when a coachee subordinates their objectives in deference to a specific superior(s) or perceived superior(s) As a coach, we want to understand what that means and how to work with or mitigate that perception and behavior.

A second dimension contrasts individualism with collectivism. In collectivism, the “we” is emphasized, in individualism the “I” is dominant. In collectivism loss of face and shame are important constructs. In individualism, it is a loss of self-respect and guilt that commands more attention. Filling obligations to family, in-groups, and society are important in collectivism while in individualism, it is more about fulfilling obligations to self. In our Central Asia example, the coach will be keen to understand issues around saving face and group-related behavioral norms. This covers a gamut of issues including how, what, when to communicate, how to behave and dress, and when to do certain things. This dimension correlates within-group expectations and can dovetail with religious behaviors. An example might be an unwillingness to confront a particular issue due to a particular constellation of people involved.

A third dimension is dedicated to distinguishing between dominant values of achievement/success versus cooperation and quality of life. Some societies have a need to excel, to polarize, to live in order to work, see big and fast as beautiful, and have admiration for the successful. Other societies emphasize more quality of life, seek consensus, work in order to live, view small and slow as beautiful, and have sympathy for the unfortunate. In our Central Asia example, this dimension can manifest itself in the area of career advancement whereby career advancement per se may play a less motivating role.

Uncertainty avoidance is a dimension looking at the extent to which people feel threatened by uncertainty and ambiguity, and try to avoid such situations. Where uncertainty avoidance is low, we find more relaxed atmospheres, there is less stress and emotions are less show. There is less of a need for rule and conflict and competition are seen as fair play. In contrast, high uncertainty avoidance correlated with anxiety, greater stress, and the need to show emotions, to release stress. We also find a need for rules and a view that conflict is threatening. In our Central Asia example, we may find a need to bridge coachee preferences for structure and predictability in the face of BANI-driven organizational initiatives to purposely disrupt and increase the change of pace in increasingly ambiguous settings.

Another dimension looks at the extent to which people show a future-oriented or pragmatic perspective rather than a normative or short-term point of view. With this dimension, it is possible to constructively expose timeframes, preferences for stability and change, conventional and pragmatic approaches, and even perspectives about truth in the workplace. In our Central Asia example, we may find organizational objectives fostering change, diversity, and inclusion at odds with normative perceptions about such initiatives. Coaching can expose the underlying beliefs while offering ways to bridge gaps, impact attitudes and change specific behaviors.

The final 6D dimension highlights the extent to which people express their desires and impulses. Relatively weak control is referred to as indulgence while relatively strong control is referred to as restraint. In our Central Asia example, this dimension can be manifested in skepticism about organizational initiatives and reluctance to accept or embrace desired changes. Here too, coaching offers a psychologically safe environment to explore, understand and focus on behavioral changes to align the individual with organizational objectives.

Equipped with a 6D understanding as a foundation, it is possible to further reduce complexity by working with culture clusters. By focusing on the first four main dimensions of national culture, clear patterns emerge as combinations related to low and high dimensional scores reveal 6 national clusters. They are referred to as; Contest, Network; Family, Pyramid, Solar System, and Machine. When working with highly complex organizations it is normal to have a myriad of nationalities collaborating. As such, the Culture Clusters are a further way to create effective insights in the face of complexity.

The culture clusters were coined by Hofstede and further refined by Huib Wursten who crafted a gestalt, the 7 Mental Images of National Culture.[10] In a short book, it is possible to cover the globe of national cultures using just 7 distinct mental images. Using Huib Wursten’s gestalt, both coach and coachee can rapidly achieve a common language and reference point to discuss issues impacting coaching objectives when they relate to national culture.

Acknowledgments

The author kindly acknowledges coachees from Central Asia who helped shape this article and provided practical relevance and learning to the author.

References

Cascio, J. (2020). Facing the Age of Chaos. https://medium.com/@cascio/facing-the-age-of-chaos-b00687b1f51d

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind, third edition (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional.

Imfeld, T. (2021). What is transition coaching? https://www.bullseyeinternational.ch/wp-content/uploads/White_Paper_Transition_Coaching.pdf

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009.

Passmore, J. (2009). Diversity in Coaching: Working with gender, culture, race, and age. London: Kogan Page.

Peterson, D. B. (2006). People Are Complex and the World Is Messy: A Behavior-Based

Approach to Executive Coaching. In D. Stober & A. Grant (Eds.), Evidence-Based Coaching Handbook: Putting Best Practices to Work for Your Clients (pp. 51-76). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Thoren, P-M. (2017). Agile People: A Radical Approach for HR & Managers. Lioncrest Publishers.

Wursten, H. (2019). The 7 Mental Images of National Culture. Hofstede Insights.

About The Author

Thomas Anthony Imfeld, born and raised in Metro New York, earned his BA and MA degrees in the USA. Working on both sides of the Atlantic, Thomas has been leading international business development at a visual communication company. He served Fortune 500 companies globally over a long period. Thomas founded and incorporated his own consultancy in 2012 working for clients in the Mobility Industry and beyond. He obtained certifications in career coaching, intercultural management, and training. Thomas uses his experience, knowledge, and networks to support individuals and organizations in change processes to secure objectives. He calls Trier, Germany, home where his son was born. Thomas is involved in the community, assisting global citizens, ex-pats, women, and neurodiverse Gen Alphas.

[1] Cascio, J. (2020). Facing the Age of Chaos. https://medium.com/@cascio/facing-the-age-of-chaos-b00687b1f51d

[2] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

[3] Imfeld, T. (2021). What is transition coaching? https://www.bullseyeinternational.ch/wp-content/uploads/White_Paper_Transition_Coaching.pdf

[4] Human Capital Institute, in partnership with International Coach Federation. (2016). Building a coaching culture with managers and leaders. Retrieved from http://www.hci.org/files/field_content_file/2016%20ICF.pdf

[5] Thoren, P-M. (2017). Agile People: A Radical Approach for HR & Managers. Lioncrest Publishers.

[6] Source of yin/yang image. https://medium.com/@cascio/facing-the-age-of-chaos-b00687b1f51d

[7] Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009.

[8] Passmore, J. (2009). Diversity in Coaching: Working with gender, culture, race, and age. London: Kogan Page.

[9] Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind, third edition (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional.

[10] Wursten, H. (2019). The 7 Mental Images of National Culture. Hofstede Insights.