Neuroscience of Inclusion: New Skills for New Times

Neuroscience of Inclusion: New Skills for New Times

Author: Shannon Murphy, MA

CEO & Co-Founder

BrainSkills@Work

Abstract

Our brain is not wired for inclusion, no matter how well-intentioned one may be. The brain needs help to engage across cultures and differences effectively. It’s a paradox that the very hallmarks of the best of humanity, such as the ability to demonstrate kindness, compassion, care, understanding, open-mindedness, and empathy, are not always easily engaged across differences.

Why is that? We have inherited a brain that operates on fear, especially fear of others who are different from ourselves, particularly when those differences are not familiar or cause us discomfort – consciously or unconsciously. It’s tied to the inherent survival mechanisms in the brain and differences that are unfamiliar, or cause discomfort get processed as a threat. The brain’s us/them dynamics have plagued humanity for millennia, with often horrific consequences that continue to play out currently in wars, killings, conflicts, and increasing polarization across differences and political divides.

The brain needs our help, and there is good news. We can learn to override our biology and leverage the malleability of the brain by engaging in self-directed neuroplasticity. By understanding how the brain engages across differences and what gets in the way of being inclusive, we can practice brain-based skills and tools that build new neuropathways, support higher levels of self-awareness, and assist in the regulation of our body’s physiology. Then, we are poised to reflect the best of humanity and make a conscious choice in every interaction to engage with care, kindness, and compassion, and in the process, shape a more inclusive brain.

Keywords:

DEI, DEI training, Leadership, Leadership training, Inclusion, Neuroscience.

Introduction: Our Brain Is Not Wired For Inclusion

Our brain is not wired for inclusion, no matter how well-intentioned one may be. The brain needs help to engage across cultures and differences effectively. It’s a paradox that the very hallmarks of the best of humanity, such as the ability to demonstrate kindness, compassion, care, understanding, open-mindedness, and empathy, are not always easily engaged across differences.

Why is that? We have inherited a brain that operates on fear, especially fear of others who are different from ourselves, particularly when those differences are not familiar or cause us discomfort – consciously or unconsciously. As human beings, we have survived as a species by protecting our own and warding off threats – the two faces of survival. It is helpful to recognize that the brain’s primary job is not conscious thought or being inclusive for that matter. Its primary job is to ensure our survival, and everything else falls farther down the list of priorities.

The brain is incredibly complex, highly networked, and intricately tied to the body’s systems and physiology. It has developed in ways to ensure our survival, and that impacts a broad range of mechanisms, from how the body uses energy, to memory and past experiences, to how we perceive and interpret the world around us. In managing the body’s resources and needs, energy efficiency and speed are critical to survival. We react and respond to threats, real or perceived, quickly and often before we have consciously processed them. Think about the last time you were driving and suddenly a car pulled in front of you, and you reacted instantly to avoid it hitting you. Or you were about to cross a street and suddenly step back as a car or bus wooshes by you before you consciously registered the danger.

While the threat response is complex, it all happens quickly, with different areas of the brain engaging, such as the amygdala and hypothalamus, and rapid changes in the body’s nervous system and endocrine system. Based on the context or situation we find ourselves in, the stronger the perceived threat, the stronger the response. This is often referred to as the fight, flight, freeze, faint, or fawn response. Which response the brain decides to act on will vary from person to person, situation to situation, and past experiences, such as trauma, that have shaped our threat responses.

The threat response of the brain is well researched and understood – how it impacts the physiology in the body and what action the brain decides to take. What, at times, is less understood is how profound this really is. We like to think we are making conscious choices. Yet, often the brain has already made a determination based on the context and situation we find ourselves in, quickly processing past experiences, and incoming sensory data while striving to run the body as efficiently as possible. This also goes well beyond the threat response and encompasses much of how we move through the world on a day-to-day basis. There is a range of opinions among neuroscientists as to the degree to which free will exists, and how much of our experience is shaped by our past experiences, conditioning, and the brain’s predictions. Some neuroscientists say there is no free will; our experiences and actions are generated entirely from our past conditioning. Others take a more mechanistic view of the brain that it is a prediction machine based on the inputs. Despite these differences, most neuroscientists do agree on something profound: many of our decisions, actions, and behaviors happen outside the radar of our conscious awareness.

Neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett states in her book, 7 ½ Lessons About the Brain, “Your brain is wired to initiate your actions before you are aware of them. This is kind of a big deal.” She describes how the brain determines our actions based on our memory, past experiences, and new sensory input. In milliseconds, the brain puts all these bits and pieces of information together, predicting and shaping what we do next. This is critical to think about when crossing cultures and being inclusive, as our culture, conditioned responses, beliefs, and biases all influence predictions the brain makes and the corresponding action one takes. This can be tricky terrain, for when it comes to inclusion and cultural agility, the brain can work both for us and against us. When we can better understand these dynamics, we can then learn to work with the brain and build new behavioral habits that support inclusion and creating meaningful relationships across differences. One aspect that is helpful to understand is the inherent social circuitry in the brain and the role it plays.

Wired to Connect

The brain has inherent social circuitry, which is what drives the fundamental need for human connection. We are social beings with a survival-based need for inclusion. Matthew Lieberman, Director of the UCLA Social Cognitive Neuroscience lab and author of “Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect,” studies the social networks in the brain. His research shows how our brains have a strong survival-based need to connect and belong, and how the brain developed the ability to join and cooperate with others to increase our collective ability to survive. According to Dr. Lieberman, the brain’s deeply embedded social circuitry is what made it possible for us to become smarter by working together, and an intrinsic human need for group belonging. The brain’s built-in social wiring is what establishes our primary need for inclusion. Dr. Lieberman states that “the human need to belong and connect with others is even more fundamental than our need for food or shelter.” ( Lieberman, M. 2013)

The social circuitry is what allows us to forge meaningful relationships with others. It represents the networks, circuitry, and pathways that support the brain’s inherent capacity for empathy, compassion, and understanding of others. To belong and feel like a valued member of the group is not just a nice thing to have; it is a brain requirement for survival. Being excluded or marginalized directly impacts this innate need for group belonging and connection. Knowing this helps us understand why experiences of social exclusion and marginalization can be so painful and often traumatic. The pain of social exclusion is real pain. Not only does social pain register in the same pain centers as physical pain, but it’s also “stickier.” Think of the last time you stubbed your toe or got physically hurt. You may recall the experience, but not feel the pain associated with that experience. Now, think of a time when you felt the pain of being socially excluded in one way, shape, or form; perhaps you were discounted, marginalized, belittled, or ignored. Chances are, as you think about it, the emotions of that painful experience come flooding back. Those experiences stay with us, and particularly for historically marginalized groups and identities, there is a cumulative impact as well. This is why cumulative microinequities are sometimes described as death by 10,000 paper cuts.

The need for social connection and meaningful relationships is so vital that when people are isolated or excluded, it impacts how effectively the brain and body function. Research studies show, for example, that being excluded interferes with the process of creating and connecting neurons in the brain, which is essential in learning new skills and behaviors. (Stiles, Joan, Jernigan, Terry L. (2010) Lack of social connection has been shown to increase the risk of increased mental health challenges, including depression, anxiety, loneliness, and cognitive decline. One study linked loneliness to a 40% increased risk of dementia. (Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti, Terracciano, A. 2020). Social isolation is shown to impact physical health, posing an increased risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, insomnia, and weakened immune system. Isolation is even linked to reduced life span. ( National Institute on Aging 2019) and (Cené CW, Beckie TM, Sims M, et al. 2022) Additionally, underscoring the importance of social connection, research shows that when young children are denied social contact including caring appropriate physical touch, such as children in institutions, it impacts brain development and functioning. More recently, studies of children born during the COVID-19 pandemic in an environment of social distancing and isolation show the negative impact on their development, with significantly lower scores in verbal, motor, and cognitive performance compared to babies born before the pandemic. (Xiong, Hong, Liu, Zhang, Y. 2022)

Intersectionality and inequities also play a role, as Tulane University research highlights that some groups have an increased risk of social isolation and loneliness, which is important to recognize from both a health equity perspective as well as an inclusion perspective. The groups identified included: immigrants, due to language, cultural and socio-economic barriers; historically marginalized groups such as BIPOC (black, indigenous, people of color), LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual), people with disabilities, due to ongoing discrimination; and older adults that live alone. (Tulane University (December 8, 2020) These studies and others show that social isolation, exclusion, and marginalization have a significant impact on people’s ability to perform at their highest and best, and negatively impact health and wellbeing.

Wired To Connect? Not Necessarily Across Differences

Paradoxically, a fundamental human need is connection, yet this is challenging across differences. While the brain has inherent social circuitry (as described above), cooperation develops in the brain within groups, not between groups, which is a central challenge. The brain unconsciously filters and categorizes every person we see as familiar/not familiar, comfortable/not comfortable. Differences that are unfamiliar or cause discomfort get processed by the brain as a threat. This is tied to the old survival mechanisms in the brain and body’s physiology when we had to quickly ascertain “friend or foe.” The brain’s us/them dynamics have plagued humanity for millennia, with often horrific consequences that continue to play out currently in wars, killings, conflicts, and increasing polarization across differences and political divides.

The brain’s base responses to differences directly impact our ability to be inclusive and work effectively across cultures. Research studies show how aspects of the social circuitry, such as the capacity for empathy, do not readily engage when the brain perceives someone as different from oneself based on any aspect of identity. For instance, in studies where subjects simply viewed photographs of people who look like them, the areas in the brain for cooperation, empathy, and self-awareness are activated. Conversely, when subjects viewed photographs of people who didn’t look like them, these same areas did not activate as strongly or in some cases, did not engage at all. (Association for Psychological Science, 2014)

This means that when we meet someone whose differences the brain perceives as familiar and comfortable, we aremore inclined to move toward that person and create connections and build trust. However, when we meet someone and the brain’s base response is not like me, or it’s a difference that causes discomfort for any reason – their political affiliation, communication style, culture, race, how they dress, where they worship or don’t, their education, their speech patterns, their job level, or any other characteristics the brain perceives is outside its comfort zone – this is no small event. When the brain registers differences as discomfort, it sends an “away” impulse and even regards these differences as potential threats. ( Wellesley College, 2015)

As a parent of a teenager with Down syndrome and speech apraxia, I see the “away” all the time when I am with her. Sometimes, it is more subtle, such as being in a restaurant and the server asks me what she wants instead of asking her directly. Other times, it is more apparent and painful, such as when she started playing with our city’s house soccer league. When she started elementary school, after years of watching her two older siblings play, she was finally old enough to join the city league. She was also the only child in the entire league with a visible disability, although I am certain there are children in the league with hidden disabilities. She was so excited! We went to picture day, and I watched the children physically move away from her in the photo line, hoping she didn’t notice to spare her that pain. We went to practice, and the soccer coach did not make eye contact with her, say hello to her, or acknowledge her in any way the entire three-month season. When I reflect on that, do I think the soccer coach was intentionally trying to discriminate against my daughter? Perhaps. What I think may be more likely is that she had never been around anyone like my daughter before, and with her discomfort, the away response kicked in and she lacked the self-awareness to notice, manage and override it. The away response happens so quickly and unconsciously, and it gets experienced as a microaggression or microinequity, even though there is nothing small about that to the recipient. From a brain perspective, we must train ourselves to notice discomfort and how it shows up in our bodies, thoughts, and emotions in order to learn to override it and engage more readily across unfamiliar differences or differences that cause discomfort.

Dr. Jennifer Gutsell of the Volen National Center for Complex Systems and formerly with the Social Interaction and Motivation Lab at Brandeis University, has studied “motor resonance” in the brain. Motor resonance occurs when wewatch another person’s actions, and it produces very similar brain activity in our brains – as if we’d performed thesame action ourselves. Dr. Gutsell’s research shows that subjects’ brains only registered motor resonance when watching people who looked similar to themselves performing an action. This same motor resonance was not evident when subjects watched others outside of their ethnic group perform the same actions.(Gutsell, J.N., & Inzlicht, M. 2010)

People also showed resonant brain activity when observing emotions in others from the same cultural or ethnic group. When members of the same cultural or ethnic groups observed sadness in members of their own group, their brains also registered sadness. When observing sadness in people of different cultural or ethnic groups, however, there was no affective resonance observed. Researchers also found that the lack of resonance effects was even more pronounced when strong dislike and prejudice towards a group were also present. (American Psychological Association, 2011)

From an evolutionary standpoint, our brains are not positioned well for inclusion. The impulses that were critical to our survivability are now getting in the way of our ability to respectfully engage with others who don’t share our same life experiences, beliefs, attitudes, motivations, and desires. This is what Dr. Joshua Greene, Director of Harvard’s Moral Cognition Lab, calls “the tragedy of commonsense morality.” (Greene, J. 2013) We are learning that the brain’s base instincts are fundamentally out of line with the needs of our current workplaces and our world. By relying on a brain that gives us information about others that is often not accurate or helpful, our opportunity to successfully operate in the new world of increasing global diversity is at risk. Dr. Green acknowledges this and goes on to say that in order to live peacefully with others whose beliefs and values may be threatening to our own, we have to learn to override what our base instincts may be telling us and that this process can feel counter-intuitive to the brain.

A New Path: Working With the Brain and Leveraging Neuroplasticity

It is clear that to consistently demonstrate inclusive behaviors and work across a myriad of differences; even when there is discomfort, the brain needs our help. There is good news. We can learn to consciously intervene and help repattern the brain’s base responses to differences. We can learn to override our biology and leverage the malleability of the brain by engaging in self-directed neuroplasticity. As research has shown, the brain can change. We can now engage in self-directed neuroplasticity and consciously influence new neuropathways in the brain. For instance, research shows that bias can be repatterned in the brain with conscious intention and work. Fear responses can be repatterned, and we can increase our ability to access self-awareness to notice, manage, and override our base responses and reactions. Every time we notice and override the brain’s base responses, we are actively building new neural connections that support inclusive behaviors. This process requires self-awareness.

Self-awareness plays a foundational role in being inclusive and culturally agile. It is a mega-competency because it’s so central to inclusion, cultural agility, leadership effectiveness, and emotional intelligence. To work effectively across differences, we need high levels of self-awareness to notice and manage our reactions. In Stamped From the Beginning: A Graphic History of Racist Ideas in America, Dr. Ibram Kendi states that persistent self-awareness is foundational in being anti-racist and dismantling inequities.(Kendi, D.I.X., 2016). The frontal lobe and prefrontal cortex play an important role in our ability to access self-awareness, and it also has mechanisms that help us notice and manage our reactions to differences.

There is circuitry, for instance, in the frontal lobe that can help us manage our biases and navigate the brain’s base responses to differences more effectively. One study looked at how the brain responded to differences in socioeconomic background. They paired people who had very different socioeconomic backgrounds, based on education level and family income, to have a conversation with each other. The study accounted for the intersectionality of identities such as race, age, and gender that could impact the conversation, and worked to match pairs in ways that would minimize these variables on the results. The study found that when they put people into the conversations across the socioeconomic differences, there was heightened activity for both people in the frontal lobe. (Neuroscience News. 2020) This study aligns with other research suggesting that the frontal lobe plays a role in regulating behaviors and avoiding bias.

The frontal lobe and prefrontal cortex help us access self-awareness when we are engaging across differences. Fortunately, our brain’s prefrontal cortex plays a vital role in our uniquely human mental ability to adapt and learn new information. Its “executive functions” include planning and programming actions, monitoring and regulating our behaviors, controlling our conscious activity, comparing the results of our actions with our initial intentions, and correcting our errors. (Panikratovaa, Y., Vlasovab, R. et al. 2020) It is what helps us see multiple perspectives; make intentional choices; consciously choose compassion and understanding over judgments, biases, and stereotypes; notice and understand the impact of our behavior on others; and engage curiosity and a willingness to learn. Most important to curious learners, it gives us the ability to override the fear circuitry that keeps us stuck in our old ways and unwilling to take calculated risks because it enables us to access self-awareness and engage in self-reflection. The prefrontal cortex is also essential in managing biases, challenging assumptions, and stereotypes, and making conscious choices to engage in new, more inclusive behaviors. (Friedman, N.P., Robbins, T.W. 2021) and (Mochol, G., Kiani, R., Moreno-Bote, R. 2021)

To move beyond our conditioned narratives of others and manage the us/them dynamics, biases, and assumptions, we need the capacities of the prefrontal cortex to manage our state and keep self-awareness online. Yet this can be challenging for the brain, again, due to the survival mechanisms. When the fear circuitry engages and the brain goes into a threat or stress response, it destabilizes the prefrontal cortex. We lose access to all the capacities that help us be inclusive, including our ability to access self-awareness and self-reflection.( Rolls, E.T. 2017). When the fear circuitry in the brain gets triggered by stress or threat responses, it reduces, and can even prevent, our ability to listen with an open mind, have empathy, and intentionally choose respectful, inclusive behaviors. This is why learning skills to manage our state and calm the fear circuitry to maintain some access to self-awareness is so vital to being inclusive and culturally agile in our behaviors. (Friedman, N.P., Robbins, T.W. (2021)

Learning Brain-Based Skills to Increase Inclusion and Cultural Agility

Learning brain-based skills can help us notice our base responses and reactions so we can override them with new, more inclusive choices at the moment. This requires strengthening metacognition and being aware of our state. Metacognition is the ability to think about our thinking, emotions, and reactions. This can absolutely be strengthened, as numerous studies show, through practices such as mindfulness. We can become more adept at observing our thoughts and emotions in the moment, which gives us important clues as to how we perceive others, and situations, and if there is any discomfort present.

We can also consciously stretch the boundaries of the brain by continuously learning about differences, a central purpose in intercultural and diversity, equity, and inclusion work. When an aspect of difference becomes better understood and more familiar, it’s easier to engage and create meaningful connections and relationships. Again, I see this with my daughter with Down syndrome. The kids who know her readily engage with her, run up to say hello, hug her and engage in meaningful conversations. They are quick to engage with her the same as other classmates who do not have Down syndrome. There is an underlying comfort and familiarity that facilitates meaningful relationships. We have to do this work very consciously across a myriad of differences and multiple aspects of people’s identities.

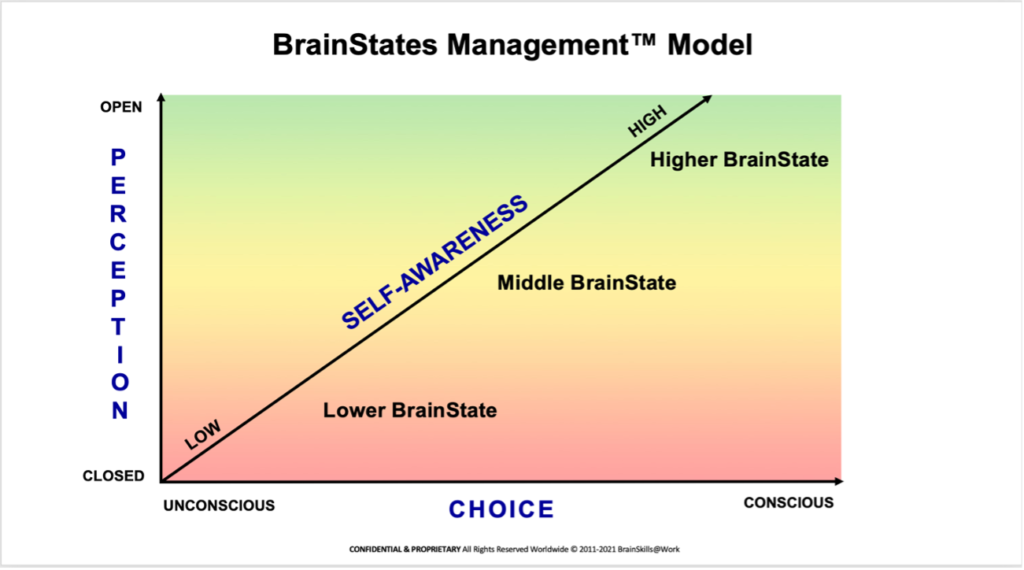

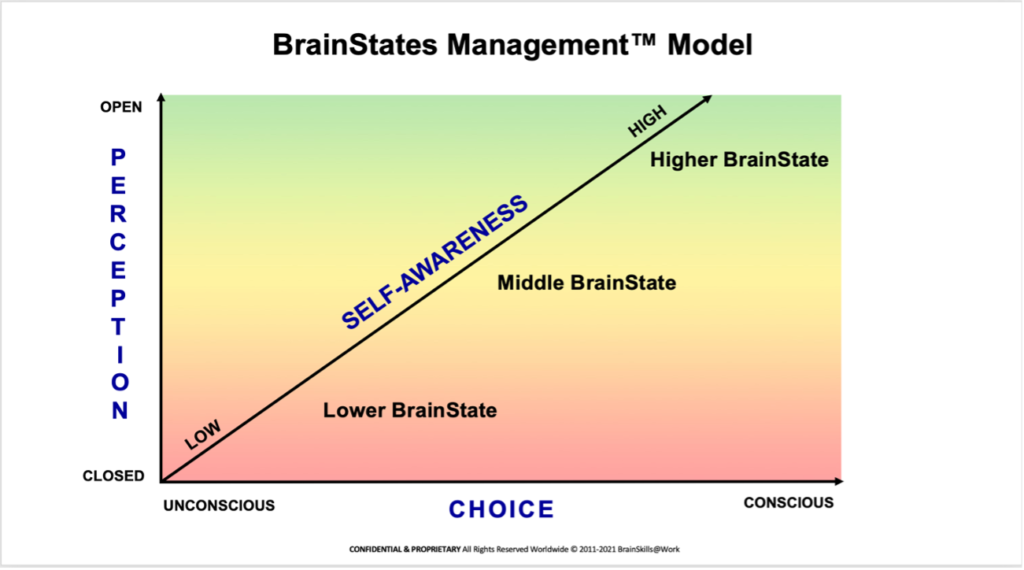

We can also become skillful in learning to manage our state, learn to quiet the fear circuitry and keep access to the prefrontal cortex. The BrainStates Management Model helps us do this. This tool provides insight into how we can keep self-awareness online and access our highest and best selves more consistently. Here is an overview of the tool.

Three dynamics underlie the BrainStates Management Model: Perception, Choice, and Self-Awareness. From neuropsychology, we know that these three dynamics are not static. They fluctuate, are interconnected, and are influenced by activation of the fear circuitry and the body’s survival-based physiological responses. Let’s look at how they work together and underlie the key concepts of BrainStates and BrainStates Management.

Looking at the model, you can see that the dynamics of Perception (left axis), Choice (bottom axis), and Self-Awareness (diagonal axis) form the building blocks of the model. Together, these illustrate the concept of three BrainStates: the Higher BrainState, the Middle BrainState and the Lower BrainState. Each BrainState represents the level of perception, the degree of conscious choice, and the amount of self-awareness available to us.

Perception: Perception in the brain, it ranges from very open at the top, where the brain can access the big picture and take in a really big field of possibilities, to a very closed perception at the bottom, where open-mindedness and seeing new possibilities is very low.

Choices: Choices in the brain can range from conscious choices, where we can intentionally engage in inclusive and respectful behaviors and align with our highest and best selves, to unconscious choices, where our behaviors, attitudes, and decisions are very unconscious, reactive, fear-based, and below the radar of our awareness.

Self-awareness: Self-awareness along the diagonal axis ranges from low to high. Being able to access high levels of self-awareness is essential for self-reflection, self-correction, and for setting and achieving personal and professional goals.

Looking at the BrainStates Management Model, the three intersecting dynamics of perception, choice, and self-awareness form three different “BrainStates.” Each BrainState involves distinct aspects of our thinking, feeling, and physiological processes. The catalyst in the brain that determines the three different BrainStates is the degree to which the fear circuitry is activated. In the Higher BrainState, the fear circuitry is not active and, therefore, the levels of perception, self-awareness, and conscious choice are more available. We can be open-minded and see a greater range of options while considering other people’s needs and concerns. We can demonstrate empathy, an important emotional intelligence competency, which is critical to establishing trust with others. In the Higher BrainState we can make conscious choices about our attitudes, behaviors, and emotions — even when a new choice may initially cause us discomfort.

When the fear circuitry starts to engage, we can find ourselves in the Middle BrainState. The threat/stress activation level in the Middle BrainState ranges from mild activation to relatively strong activation and, therefore, perception, self-awareness, and conscious choice also range from slightly diminished to greatly diminished. At the higher end of the Middle BrainState, there are low levels of stress or threats online, resulting in states such as anxiety, worry, agitation, or preoccupation. However, at this higher end of the Middle BrainState we can still focus on the work and be productive, but not at our highest and best levels of performance. In the lower end of the Middle BrainState the threat/stress response is more strongly activated. The stronger the threat, the more the fear circuitry engages and the more perception in the brain narrows. At the same time, self-awareness diminishes and the tendency to act from old, unconscious habits and patterns increases. All these factors cause even greater fluctuations in our thinking, emotions, and reactions, which can make the Middle BrainState challenging at times.

In the Lower BrainState, the threat/stress response is fully activated, perception becomes narrow, and self-awareness and conscious choice can be completely reduced. This BrainState is strongly associated with the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the fight/flight/freeze/faint/fawn response, which often results in strong defensive reactions. In this BrainState it is exceedingly difficult to intentionally choose inclusive attitudes and behaviors, and we are least able to notice how our behavior is impacting others.

We can fluctuate in and out of different BrainStates, even in a single day. It’s important to note that in the right context, all the brain states serve an important function. My family is still a family because of the Lower BrainState. When my younger two children were 11 years old and seven years old respectively, they made the poor decision to have hard candy while bouncing on the trampoline in our yard. My youngest daughter choked, and thank goodness the Lower BrainState kicked in, and my 11-year-old performed the Heimlich maneuver on her multiple times until the candy was dislodged, flew across the trampoline, and my youngest daughter could breathe again. Only then did the 11-year-old scream for help, one of those blood-curdling screams that as a parent is bone-chilling and every worst-case scenario flashed through my mind as I raced outside into the yard. What was interesting was the 11-year-old could not share what happened until hours later when their body’s physiology had calmed down enough to coherently share what happened. Our BrainStates are also significantly influenced by circumstances in the environment, as well as our overall physical health, amount of sleep, diet, and exercise. This fluctuation also provides the opportunity to learn to notice and manage our BrainStates and keep ourselves working from our highest and best selves.

Learning to notice and manage BrainStates has a positive impact on increasing our ability to be culturally agile and inclusive more consistently. One organization taught their 300 top leaders BrainStates Management, including the skills to recognize BrainStates and shift to a higher BrainState to keep more awareness online. In conjunction with this skill-building training, each leader completed the BrainStates Awareness Profile, a self-reflection tool designed to give insight into one’s BrainState tendencies. The BrainStates Awareness Profile measures seven neuroscience-based dimensions underlying BrainStates Management. They received one-on-one coaching and targeted skill development based on their individual results. The leaders also took the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) as a baseline measure.

One year later, after practicing the BrainStates Management skills and receiving ongoing “boosts” to keep the skills front and center, they completed both the BrainStates Awareness Profile and the IDI again. Interestingly, the leaders that improved their BrainStates scores and moved from the Middle BrainState as a tendency into the Higher BrainState as a tendency also progressed on the IDI. The results showed:

- 30% increase moving into the Higher BrainState as a tendency

- 60% increase moving into the intercultural mindsets of Acceptance/Adaptation

The leaders that scored in the Higher BrainState as a tendency also had higher engagement scores with their teams, increased retention, and increased diversity hiring for new positions. The leaders who did not increase their score in the BrainStates Awareness Profile and remained in the Middle BrainState as a tendency also did not progress in the IDI and had lower engagement scores. By learning the BrainStates Management skills, they were able to increase their cultural agility and inclusive leadership significantly.

Making a Conscious Choice: Demonstrating Care and Kindness

Although it’s impossible to change our past, with some intentional effort, we can change how the brain will respond both in the moment and in the future. As we practice brain-based skills, we are strengthening the brain’s ability to work across differences more effectively. Everything we learn and practice today seeds our brain to respond differently tomorrow, which results in performing new, more inclusive behaviors.

We can shape a more inclusive brain. We can intentionally draw the circle wider to include more complexity of identities. We can make a conscious choice in the moment to demonstrate the best of humanity – to engage with others with care, compassion, and kindness. We can leverage the best of the human spirit, override our biology, and intentionally demonstrate the best characteristics and versions of ourselves. We know this is possible because we have all seen it and done it ourselves. Think about when you reached out to someone in need, you paused and were more kind to the person on the phone helping you resolve an issue, you apologized to someone, or you demonstrated genuine care toward someone else.

We are inspired when we see breathtaking examples of the best of humanity and altruism in action, such as the Kenyan runner Abel Kiprop Mutal, who was confused about where the finish line was, and Spanish runner Ivan Fernandez Anaya, pushed him to the finish so that he could win. Even though Anaya could have run right past him, he chose instead to help him win. Or a Nebraska man who risked his own life to save three people from a car that had flipped upside down into an icy pond and was quickly filling up with water and the people inside would not have gotten out without his help. There are a multitude of examples of people rising up and exemplifying the best of humanity in action.

We have all seen people reach out in kindness and demonstrate care and tremendous compassion. I saw it on the second-grade soccer field. My youngest daughter with Down syndrome had worked hard all season, even though she had not scored a single goal. It was the last game of the season, and with only two minutes remaining, her coach called a time-out. I was perplexed, as they didn’t really keep score at this age, and the kids were far more interested in chasing a butterfly that happened to cross the field than engaging in soccer strategy. I watched the coach huddle the team together, and talk with them briefly, then he went and spoke with the other team’s coach. That coach huddled his team together briefly, and then they resumed their places on the field, except for one notable difference. My daughter was placed in the center-forward striker position. When the play resumed, she moved the ball down the field and, with a well-placed kick, scored her first goal of the season. To see the joy in her face as she jumped up and down, and the joy in both teams’ faces as they jumped up and down, and everyone on the sidelines on their feet cheering for her is something that will always stay with me and still brings tears to my eyes. I saw the best of humanity that day. I know what we are truly capable of when we make a conscious choice to act with love and care.

By understanding how the brain engages across differences and what gets in the way of being inclusive, we can practice skills and tools that build new neuropathways, support higher levels of self-awareness, and assist in the regulation of our body’s physiology. We can stretch the boundaries of the brain to make unfamiliar differences more familiar and comfortable. We can override the threat response and unconscious away responses, and every time we notice and override these responses, we are actively building new neural connections that support inclusive behaviors. Then we are poised to reflect the best of humanity and make a conscious choice in every interaction to intentionally engage with care, kindness, compassion, open-mindedness, and empathy, across differences. It is a conscious choice we have to make as human beings in every interaction we have. Perhaps it’s the most important decision we can make, for the choices we make today shape our brain of tomorrow.

Acknowledgement:

I want to thank Mary E. Casey, co-founder of BrainSkils@Work and co-author of our book Neuroscience of Inclusion: New Skills for New Times. I am so grateful for you, and the neuroscience of inclusion exists because of our mutual love of neuroscience, making the science practical, and our partnership

Literature:

Sapolsky, R. (2023). Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will. New York Penguin

Fridman, Joseph (2021, January 25) The dangers of seeing human minds as predictive machines. Retrieved from:https://aeon.co/essays/on-the-dangers-of-seeing-human-minds-as-predictive-machines

Feldman Barrett, L. (2020) 7 ½ Lessons About the Brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (p. 77)

Lieberman, M. (2013) Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect. Oxford University Press

Stiles, Joan, Jernigan, Terry L. (2010, December 20) The basics of brain development. SpringerLink. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2989000/

Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti, Terracciano, A. (September 2020) Loneliness and Risk of Dementia. The Journal of Gerontology. Retrieved from: https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/75/7/1414/5133324

National Institute on Aging (April 23. 2019) Social isolation, loneliness in older people pose health risks. Retrieved from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/social-isolation-loneliness-older-people-pose-health-risks

Cené CW, Beckie TM, Sims M, et al. (August 4 2022) Effects of objective and perceived social isolation on cardiovascular and brain health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. JAHA. 2022;11(16):e026493. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.026493

Xiong, Hong, Liu, Zhang, Y. (November 25, 2022) Social Isolation and the brain: effects and mechanisms. Nature: Molecular Psychiatry. Retrieved from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-022-01835-w

Tulane University; School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine (December 8, 2020) Understanding the Effects of Social Isolation on Mental Health. Retrieved from: https://publichealth.tulane.edu/blog/effects-of-social-isolation-on-mental-health/

Association for Psychological Science (September 8, 2014) Faces are more likely to seem alive when we want to feel connected. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologicalscience.org/news/releases/faces-are-more-likely-to-seem-alive-when-we-want-to-feel-connected.html

Wellesley College (July 29, 2015) Prejudice causes the perception of threat: Study suggests that threat can be used to justify actions that result from prejudice. Retrieved from: https://www.wellesley.edu/news/2015/july/node/66581

Gutsell, J. N., & Inzlicht, M. (2010). Empathy constrained: Prejudice predicts reduced mental simulation of actions during observation of outgroups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(5), 841–845.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.03.011

American Psychological Association (September 1, 2011) Perception of facial expressions differ across cultures.Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2011/09/facial-expressions

Greene, J. (2013) Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason and the Gap Between Us and Them. Penguin Books

Kendi, D. I. X. (2016). Stamped from the beginning. Avalon Publishing Group.

Neuroscience News. (October 5, 2020) How the brain helps us navigate social differences. Retrieved from: https://neurosciencenews.com/dlpfc-social-differences-17126/

Panikratovaa, Y., Vlasovab, R. et al. (2020) Functional connectivity of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex contributes to different components of executive functions. International Journal of Psychophysiology 151 pp. 70 -79

Friedman, N.P., Robbins, T.W. (2021) The role of the prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacol. Retrieved from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-021-01132-0

Mochol, G., Kiani, R., Moreno-Bote, R. (2021) Prefrontal cortex represents heuristics that shape choice bias and its integration into future behavior. Current Biology. Retrieved from:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982221001330

Rolls, E.T. (2017). Limbic structures, emotion, and memory, reference module in neuroscience and biobehavioral psychology. Elsevier. Retrieved from: https://www.oxcns.org/papers/568%20Rolls%202017%20Limbic%20structures,%20emotion,%20and%20memory.pdf

Friedman, N.P., Robbins, T.W. (2021) The role of the prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacol. Retrieved from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-021-01132-0