INCLUSIVE LEADERSHIP: FINDING SOLUTIONS THROUGH CULTURAL COMPETENCE

INCLUSIVE LEADERSHIP

FINDING SOLUTIONS THROUGH CULTURAL COMPETENCE

Elizabeth A. Tuleja, Ph.D.,ACC.

Abstract

The world is unsettled as societies attempt to reset what people think about diversity, equity, and inclusion. Leaders of organizations strive to find the “right” program to “train” its people with grand hopes that a short seminar will make a lasting difference, only to find that change doesn’t happen. Unfortunately, many traditional programs do the opposite of bringing people together; rather, people can feel named, blamed, and shamed. This article approaches the DEI topic with a developmental approach at the individual level that encourages a person to delve deep into who they are and why they think, believe, and behave the way they do. It proposes solutions based upon cultivating cultural competence. It also addresses the skills needed to become an inclusive leader and how cultural competence helps create solutions to diversity challenges within organizations.

It’s divided into two parts. The first part presents the capabilities of an inclusive leader along with some techniques and a model for dialog. It demonstrates what the skilled, inclusive leader does to solve a problem. However, tips and techniques are not enough. The second part provides a way forward demonstrating how a successful inclusive leader gains cultural competence. It explores what a leader needs to learn via an ongoing developmental process (over time, with reflection, and through coaching) in order to develop the cultural competencies needed to become a skilled, inclusive leader.

Key Words: Cultural Competence, Assessment, Intercultural Development Inventory, Diversity and Inclusion, DEI

+ + + + +

Describing the problem

In today’s sensitive workplace, everyone’s on edge regarding diversity and inclusion issues. People are afraid of offending someone and then being disciplined or even losing their job.

Organizations strive for more diversity and inclusion within the workforce. With this comes the pressure to ensure that individuals feel included and have a voice. In theory this should be a given. But hiring talent from diverse backgrounds is not enough. With diversity comes complexity – complexity of values, beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and life experiences which can lead to misunderstanding, conflict, and distrust among employees.

Concerns about politics, religion, gender, age, ability, race, ethnicity, social issues, and more are at the forefront of employees’ minds. Discord rather than harmony is created when people emphasize their perspective as others become more defensive and polarized in response.

The problem is that organizations don’t become inclusive just because there’s diversity. And people don’t get along simply because they’re told to or are required to attend awareness workshops or one-off training sessions. Whether an organization is engaged in a merger and acquisition across borders or even within its own – differences have to be identified and unity created.

PART I

Often, no matter how skilled a leader may be, the issues are complex, emotional, and potentially explosive. Leaders experience relational fatigue and stress while trying to manage their team when sticky situations arise. It can feel like walking a tight rope.

While current challenges involving diversity, equity, and inclusion abound, it is possible to find solutions through developing intercultural competence and using it to impact one’s own circle of influence. It’s a powerful development process that yields results on a lasting level.

The following is a real life event that will serve as a starting point for the discussion throughout this article. While this incident happened in an educational setting in the USA, you can change the characters to fit your organization’s makeup and cultural context.

It happened like this: An instructor sang a refrain from an African American spiritual directly related to that day’s history lesson. A student filmed and posted it to social media. In reaction to the viral video the administrators required sensitivity training for the instructor.

Cultivating inclusive leadership

In the situation described above, how could the leadership team have taken a proactive stance rather than a reactive one in order to thrive rather than simply survive in these turbulent times? The key is to develop inclusive leadership capabilities.

What is an inclusive leader? Inclusive leaders are aware of their unexamined assumptions and are able to recognize different perspectives by withholding judgement as they adjust their responses to the challenges that come their way. They don’t rush to action but take a step back to consider all angles of the situation. They are bridge builders who recognize that differences exist and find ways to bring people together. They have learned to actively seek opportunities to learn about others – this makes collaborating, managing their teams, and making decisions more effective.

There are three things that cultivate inclusive leadership.

- Inclusive leaders understand the connection between diversity and inclusion. Diversity is the mix of people in an organization – it’s the differences represented by various groups (e.g., instructor, student, administrators) who are represented within the organization. Inclusion is making the “mix” work by helping people feel valued for who they are and what they bring to the organization. This is established through organizational structures and policies to ensure engagement and contribution. Inclusion is assessed by how well an organization and its leaders value its diversity andhow it pragmatically sets procedures in place to be ready when challenges arise.

For example, how can diverse teams manage their differences in order to achieve better business results while at the same time improving employee engagement? People are going to disagree. They will say or do things that are misinterpreted. Inclusive leaders work towards a corporate culture where all members feel respected, valued, and safe regardless of their position. When an instance arises, the leadership team’s top priority is to ensure that all parties involved are heard, are treated fairly, and are not afraid of the power dimensions.

In the beginning scenario, it would have benefited all to understand the context of the lesson, the learning goals of the instructor, the motives of the student, and the underlying concerns of the administrators. There were missed opportunities for learning and personal growth that could have come out of this situation rather than rushing to take action. Understanding what diversity and inclusion mean is the first step to becoming an inclusive leader. This leads to the second point.

- Inclusive leaders look at situations from multiple points of view. They examine an event from a stakeholder perspective. This would include the following:

WHO. Identifying who were the primary groups involved (instructor, student, administration)? Who are the secondary groups that could also be affected (e.g., the student body, other employees, the public, the donors)?

WHAT. Asking what were the respective needs, perspectives, possible motivations regarding what happened? Was the student upset and needed to talk to someone about an underlying issue? Thought it was funny? Wanted to get “likes” on social media? Perhaps the student thought it was a great lesson and wanted to share it with others.

HOW. Encouraging how each stakeholder’s role contributed to the situation. Perhaps the instructor could have demonstrated sensitivity and collaboration beforehand by asking students their opinions rather than just assuming. This also includes examining how the organization plans for situations and how they choose one response instead of another.

In the opening scenario there was a rush to judge one person over another rather than trying to understand all points of view. When strategies aren’t in place, those in leadership positions by default put themselves into a reactive versus proactive stance. The inclusive leader understands that each person must be heard and feel valued without a rush to judgement. Rather than assume the worst and respond with a knee-jerk reaction, there should be a calm discussion from all angles. Everyone has their own needs, motivations, and limitations which are based on the underlying values, beliefs, and attitudes that people often aren’t even aware of. To include only one perspective is to exclude the other. This leads to the third point.

- Inclusive leaders invite all stakeholders into a dialog. The goal is for everyone to take a step back and think about what happened by giving benefit of the doubt. The leadership team must talk through the incident with the instructor to understand their motives and purposes. The leadership team must create a safe environment for dialog with the student about their motives and reasons. The leadership team must also think about their reaction and examine what decisions might have been made by hasty assumptions. Then, the leadership team must involve administrators, instructors and students working together to create a structure that could be used in the future to open DIALOG rather than shut down and name, blame, shame – because as a result valuable learning opportunities that were missed.

Creating workable solutions through dialog

Inclusive leaders understand that everyone is “on edge” and worried about saying the wrong thing. Inclusive leaders LEAD WITH THEIR EARS. It’s about listening skills and empathy. It’s about withholding judgement and not making assumptions. Here’s what this means when considering the mix of people to make them feel included. A skilled, inclusive leader is able to:

Determine what happened

Initiate conversation

Acknowledge other perspectives

Let go of judgement

Open up opportunities for all

Give benefit of doubt

Using this framework of DIALOG could have helped the administrators when dealing with the problem of the singing sage.

However, this is “all well and good.” While using this mnemonic is useful in theory, it is difficult in practice.

Leadership skills aren’t formed overnight. It’s a developmental process that enables a person to understand who they are; understand who others are; and then understand how they react to differences. When a leader uses the DIALOG framework, it becomes their new superpower. They learn to listen more and talk less by finding out where the other person is coming from – and then truly listening to understand based upon the person’s perspective.

While it’s natural to think about your response when someone else is speaking, when you lead with your ears, you are putting that person’s needs above your own – you are then able to ask non-judgemental questions that inform you about their perspective rather than trying to promote your own. You learn how they see the world and frame issues that matter to them.

Inclusive leaders understand how to make the “mix” of a diverse group of people feel included; how to look at issues from the point of view of all involved; and how to invite those people into dialog and learn from each other.

PART II

Taking action through self-development

The first part of this article discussed the challenges of diversity and inclusion along with introducing what inclusive leaders do to be successful. Now we’ll turn to how they develop cultural competence which is the foundation for dealing with cultural differences.

Introducing a pithy acronym such as DIALOG is a helpful model, but in reality, creating a dialog around difficult conversations is easier said than done. It’s great advice, but so is much of the information available today regarding diversity and inclusion initiatives. There’s plenty of advice on what leaders should do (e.g., determine…initiate….acknowledge). But very few solutions exist (e.g., exactly how does one suspend judgement and listen to understand when one’s belief system is threatened?). While needed, most of the talk and training around diversity, equity, and inclusion comes in the form of awareness training that is external and doesn’t necessarily last. Why is that? If we are to truly develop successful inclusive leaders, then we must step away from mere talk and get to the heart of the matter – which originates in the internal attitudinal and behavioral habits of the individual.

The second part of this article focuses on a way forward to help individuals change their attitudes and behaviors from the inside-out and do so without giving up their values and beliefs. It examines a critical developmental process via a scientific assessment tool (IDI-Intercultural Development Inventory)[1] that effectively helps individuals and groups identify and explore areas of cultural differences and similarities in order to navigate them more effectively.

What is cultural competence?

The key to linking diversity (the mix of people) and inclusion (the mix of people feeling valued) is cultural competence, which is the capability to shift cultural perspectives and appropriately adapt behavior to cultural differences and commonalities. When one develops intercultural competence, one gains a more complex understanding of how to engage cultural diversity. This developmental process enables a person to grasp that people from other groups have different ways of making sense and responding to cultural differences. A significant result is that people begin to identify such differences and establish accurate commonalities to produce a shared experience through the recognition of goals, needs, interests and motivations. There is no quick fix to solving diversity and inclusion issues in the workplace or around the world. But taking the time to identify, reflect on, and alter one’s attitudes and behaviors for more effective personal leadership will yield positive results. We must first evaluate our unconscious assumptions – learned through our cultural backgrounds – and then redirect them appropriately. If we believe that it’s someone else’s responsibility to fix what is broken, we have missed the mark because we all have a part in helping to solve the problems in our organizations, communities, and the world.

This quote by Gandhi is appropriate for the discussion.

We but mirror the world. All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a [person] changes [their] own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards [them]. This is the divine mystery supreme. A wonderful thing it is and the source of our happiness. We need not wait to see what others do.[2]

This means that social transformation must go hand in hand with personal transformation. Each of us has the opportunity to effect change within our own circle of influence – by becoming aware of our unexamined assumptions and going through a developmental process that will grow our cultural sensitivity. We can make a difference because we start with ourselves – and we become the change.

But how do we do this? How can we implement a model of DIALOG for difficult conversations? How can we change our attitudes towards others without sacrificing our core values? This is no easy feat as it takes grit, which is the courage and perseverance needed to improve oneself. Transformation occurs through the tough inner work of becoming aware, reflecting mindfully, exploring possibilities, making mistakes, and trying again and again. It is a constant process of life-long learning.

In decades of teaching, coaching, and consulting, I have developed an approach when it comes to working with professionals from around the world who want to grow their inclusive leadership.[3] A way to do this is via an exceptional scientific assessment tool that proves effective and is based on a developmental model of intercultural sensitivity.

Developing cultural competence through intercultural sensitivity

The IDI – Intercultural Development Inventory

The IDI – Intercultural Development Inventory – is a scientifically validated and reliable psychometric tool that assesses a person’s orientation regarding difference.[4] It consists of a continuum of 5 stages (orientations) of development with the goal of moving from a monocultural mindset to an intercultural mindset. These mindsets indicate a person’s orientation towards interacting with people and situations different from them. The goal is to move towards intercultural sensitivity.

A monocultural mindset is when a person sees things only through their own cultural worldview (which includes their values, beliefs, behaviors). This can result in an ethnocentric viewpoint regarding how one perceives and experiences cultural diversity. A person in this mindset isn’t able to identify the differences between their own perception and that of others who are culturally different –their reality is the only right reality.

An intercultural mindset is the capability of shifting one’s perspective and adapting behavior to the cultural context and situation. This doesn’t mean that a person needs to let go of their values and beliefs; it simply means that they are able to “put themselves in someone else’s shoes” or “see life through their lenses” and recognize that they have different “lived experiences.”

The IDI provides an objective assessment of an individual’s or group’s reaction to cultural differences and similarities and then provides a way forward with the goal of moving away from a monocultural towards an intercultural mindset. This is done through a personal action plan based on awareness, reflection, and continuous learning. The reflection exercises in the personalized action plan are meant to be revisited again and again, since developing intercultural competence is an ongoing learning process that never ends.

In the beginning of this article, we discussed what inclusive leaders do. Using a tool such as this is a method in which a person learns to develop the cultural competence – the skills – needed to become an inclusive leader. Because this is a developmental process, it’s necessary to examine the five stages that lead to intercultural sensitivity.

Stages of intercultural sensitivity

Denial

The first stage in the monocultural mindset is the denial of differences. It reflects a more limited experience and limited capability for understanding and responding appropriately to cultural differences regarding values, beliefs, perceptions, emotions, and behaviors.[5]

A person in this orientation makes uninformed observations about culturally different “others” or makes superficial statements of tolerance. They are uncomfortable acknowledging that differences exist, or even miss the fact that differences exist at all. This is from having limited contact with people outside their in-group. Therefore, this orientation leads to broad stereotypes and overgeneralizations of the “other.”

While people within this stage may not intentionally seek to demean people or groups through stereotypes, their lack of awareness may incline them not to notice unjust policies, such as not being aware of how certain practices are promoted and affect others in non-dominant groups.

Polarization

The second stage is polarization where people are unable to recognize the depth of critical issues that are important to people with a different background. So, out of defense, they are critical of other viewpoints and favor their own. This happens when people begin to interact with others who are different – or are presented with a crisis that forces people to face uncomfortable situations or deal with serious societal problems.[6] An evaluative mindset develops where a person views others as “us versus them.”

This manifests itself as people in non-dominant groups who become frustrated with colleagues or leaders in control of policies that affect them negatively. On the other hand, people in such positions of power may feel threatened by pushback when individuals or groups try to make themselves heard. As a result, people become polarized about important issues and react with defense.

Minimization

The third stage is minimization where a person begins to find commonalities between themselves and people of other cultures. It’s called the transitional stage because this orientation means that a person sees differences. In this stage, people recognize that there are differences rather, don’t deny that differences exist, or become defensive. It’s an orientation that highlights cultural commonality and universal values and principles for all.

However, by thinking that all humans are the same, this masks the deeper recognition and appreciation of cultural differences. On the surface this stage appears to be sensitive because one thinks that the common ground of shared humanity can put aside our differences. But in reality the minimization of cultural difference occurs when a person assumes that their own cultural worldview is shared by others. For example, in a group someone makes a statement about politics, policies, or practices. This minimizes the fact that not all people agree, but the person making the comment assumes everyone is on the same page.

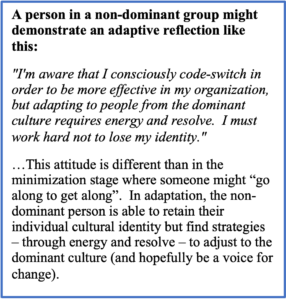

Statements like this may not be meant to hurt someone, but actually masks the deeper issues that suppress the concerns experienced by people in non-dominant groups. There is no inner reflection of the effect this has on others. But as a reaction, people in non-dominant groups will often “go along to get along”, which is a result of minimization.

The bad news is that this is the hardest stage to move out of because most people think that they are o.k. since they respect others as they would themselves.[7] But the good news is that with this awareness and knowledge a person can begin to see things from the perspective of someone else – and then adjust our attitudes and behaviors.

Acceptance

Once a person moves through the monocultural mindset through the transitional stage of minimization they enter into the intercultural mindset. This is when they are able to look at the complexity of issues and see both sides. What is being “accepted” at this stage is a recognition of the equal but different complexity of others.

A person in acceptance realizes that worldviews are complicated and theirs is just one of many. This doesn’t diminish their worldview – they don’t have to agree with someone else’s worldview – it’s simply a realization that others believe, think, and act differently.

This stage is characterized by:

- Recognising and appreciating cultural difference

Understanding that their cultural perspective is just one of many

Understanding that their cultural perspective is just one of many- Feeling confident in not having to agree.Recognizing and appreciating cultural difference

In this stage, people are curious about cultures and want to create mutual understanding. Their perceptual awareness is emerging and they want to bridge the gap, but don’t necessarily know how to do it. They are not yet able to adapt their behavior and responses to different cultural contexts. In order to move from this stage, learners need to gain culture-specific knowledge.

Adaptation

Adaptation is the most advanced capability to shift behavior based upon cultural situations and contexts. In this stage a person knows how to produce alternative behaviors that are appropriate. There is a deeper self-awareness, understanding, and empathy that enables them to experience the other’s world “as if” they are part of that culture. This evolves from much exposure, experience, and intentional learning about cultural differences.

This doesn’t mean that a person is perfect and does not make mistakes. The adaptive person is aware of steps and missteps and is constantly checking their conscious or unconscious competence. As a result, they:

- are conscious of reframing cultural information and observations in various ways

- are able to make sense of cultural differences in ways similar to people from another cultural group

- have high value and commitment to intercultural competence for self and others are able to bridge differences.

Such knowledge is extremely valuable, but knowledge alone is not what people need to solve diversity, equity, and inclusion challenges in their organizations. An assessment tool like this one just describe powerfully enables individuals and groups to develop the cultural competence needed to become inclusive leaders. Users take the assessment, learn about the framework, are debriefed by a certified coach, and begin to work on an action plan that has learning goals specific to an individual’s orientation. The action plan is a guide to be worked through and reevaluated again and again. This developmental process is reflective and ongoing as the individual is objectively how to develop intercultural sensitivity. There are no quick fixes.

How cultural competence can solve diversity and inclusion problems

Using an assessment tool that objectively provides a snapshot of where a person is at and what developmental steps they should take – combined with coaching over time – can help individuals and groups “become the change” within their circle of influence. This developmental learning is not for the “faint of heart” as it takes time, patience, and perseverance. It also takes courage: courage to look within and acknowledge that each of us is part of the problem; courage to commit to dealing with unexamined assumptions; courage to make changes in their attitudes and behaviors; and courage to even to explore cultural worldviews with which they disagree or are uncomfortable.

Reflecting back on the opening scenario with the misunderstanding of the instructor, student, and leadership team, if this was your organization, what would have been your course of action? How could you have satisfied all of the many primary and secondary stakeholders?

Imagine being able to talk about the tough issues around immigration, ethnicity, race, disability/ability, gender, and other issues, where people listen and try to understand rather than become defensive and polarized out of fear, discomfort, or frustration.

- Rather than denying differences exist, you work with others in your organization and become comfortable acknowledging them – from multiple perspectives so that people in non-dominant groups feel they have a voice.

- Rather than becoming defensive and polarized about what you learn as an organization from these discussions, you figure out a way to work through the discomfort with these new revelations.

- Rather than trying to gloss over differences by minimizing them and hoping everyone will be happy, you help people become comfortable with seeing difference by talking about the hidden dimensions of culture: values, beliefs, and behaviors – all of which make up who we are.

- Rather than wondering how to move beyond acceptance, you pull from your most valuable company resources – the people itself – and seek ways to take the positive acceptance of each other and move it towards adaptation– to help the entire organization together.

Imagine people in your organization one day being able to say that they feel included, understood, listened to, and a vital part of the organizational culture all because the leaders were in a constant process to develop their cultural competence and ensure that the entire organization did as well.

Conclusion

This article provided a solution to developing inclusive leaders who can help effect change in their organizations through cultural competence.

The first part of this article illustrated WHAT successful inclusive leaders do. It demonstrated the importance of looking at all sides of an issue while suspending judgement and looking for observable facts. Then it provided a model – DIALOG – to get people thinking about how to respond to differences in ideas, opinions, and values. The second part of this article examined HOW to develop that success by describing a scientific assessment tool that when used consistently, over time, and with a trained coach, will yield great results.

The critical link between awareness and action when dealing with DEI concerns is cultural competence. The successful inclusive leader is both curious and willing to interact with diverse others even when there is uncertainty and ambiguity. They learn about their own culture and those of others and challenge assumptions without losing their identity. They develop the capacity to be flexible around different worldviews and are not threatened by them. And they are able to take action – to be successful and to regroup when they make mistakes.

The world has and will always have problems and challenges relating to cultural diversity. But each of us, growing in our skills and wisdom, can help create positive change – one person at a time – starting with ourselves. We may not be able to change the world, but we can have that ripple effect within our own circle of influence – if we have the courage to become aware, gain knowledge, engage in reflection, and cultivate the competencies so desperately needed in our multicultural global world. It can be done.[8]

Literature

[1] Hammer, M. R., & Bennett, M. J. (2009). The intercultural development inventory. Contemporary leadership and intercultural competence, 16, 203-218.

[2] Good Reads. Retrieved May 10, 2023 from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/760902-we-but-mirror-the-world-all-the-tendencies-present-in.

[3] Tuleja, E. A. (2021). Intercultural Communication for Global Business: How leaders communicate for success. Routledge, pp. 54-56.

[4] Paige, R. M. (2004). Instrumentation in Intercultural Training. In D. Landis, J.M. Bennett & M.J. Bennett (Editors). Handbook of intercultural training (3rd edition) (85-128). Thousand Oaks: CA. Sage.

[5] IDI Inventory. Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://idiinventory.com/generalinformation/the-intercultural-development-continuum-idc/.

[6] Bennett, M. J., & Hammer, M. (2017). A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. The international encyclopedia of intercultural communication, 1(10).

[7] The Intercultural Leader Institute. Retrieved May 5, 2023 from https://www.theinterculturalleader.com/about.

[8] The Intercultural Leader Institute. Retrieved April 10, 2023 from https://www.theinterculturalleader.com/inclusive-leadership

If this article has sparked your curiosity and you’d like to learn more how you can become an inclusive leader through the developmental process of intercultural sensitivity, connect with me on Linked In https://www.linkedin.com/in/theinterculturalleader/ and visit www.theinterculturalleader.com for more information.

Understanding that their cultural perspective is just one of many

Understanding that their cultural perspective is just one of many