A Call for Many Peaces:

A Call for Many Peaces:

The Power of Hibakusha Stories and Cultural Analysis of

the Concept of Peace

By Reiko Tashiro, CQ Lab, Japan reiko.tashiro@cqlab.com

ーーーーーーーーーーー

SUMMARY:

In today’s world, conflicts persist even 80 years post-World War II. The recent suggestion of tactical nuclear weapon use by Russian President Vladimir Putin highlights the growing threat of nuclear warfare, underscoring the urgent need to preserve the narratives of aging hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors). This article delves into the societal impacts of hibakusha stories, recounting the experiences of a survivor and their testimonial activism. It examines how these narratives influence grassroots movements. In the latter part, it questions the dominant notion of peace and the cultural influences on it. Hypothesizing that prevailing peace paradigms reflect specific cultural values, it calls for a more culturally inclusive approach to peace studies. This article serves as a starting point for studying diverse cultural manifestations of peace.

*” Hibakusha” refers to survivors of either the atomic bombing at Hiroshima or Nagasaki in 1945.

KEYWORDS: Hibakusha, Nuclear Weapons, Story Telling, Positive Peace, Cultural Worldview

ーーーーーーーーーーー

INTRODUCTION:

It has been approximately 80 years since the first atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite numerous efforts towards nuclear disarmament and abolition since then, as of early 2022, it is estimated that nine countries, including the United States and Russia, possess a total of 12,705 nuclear weapons (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2022). The belief in the nuclear deterrence theory remains strong in maintaining peace. The U.S. Department of Defense stated that the country’s highest nuclear policy and strategy priority is to deter potential adversaries from nuclear attacks of any scale (2018). The Escalating tensions among nuclear-armed states, along with the proliferation and modernization of nuclear arsenals, and the increased risk of accidental nuclear use, contribute to a growing threat.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists which symbolizes the proximity of humanity to catastrophic destruction through its Doomsday Clock, set the clock hand to its closest to midnight (90 seconds) in 2023, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The journal maintained the same setting in the following year and stated that ominous trends continue to point the world toward global catastrophe.

In the first half (Part 1) of the article, the focus is on the impact of hibakusha stories on society. Japan stands as the sole nation to have experienced atomic bombings in wartime. Therefore, it is essential to pass down the experiences of aging hibakusha. The narrative begins with the author’s mother, Toshiko Tanaka, a hibakusha who survived the bombing of Hiroshima. It details her experiences of the bombing and testimonial activities since 2007.

In the latter half (Part 2), a hypothesis is posited that today’s peace studies are influenced by certain cultural perspectives. As evidence, Johan Galtung’s Positive Peace (PP) and the Positive Peace Index (PPI) developed by the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) are explored. Analyzing the top rankings of PPI using Hofstede’s 6-Dimension Model and Wurstein’s 7 Worldviews, it is noted that PPI rankings notably skew towards cultures characterized by individualism and low power distance. Considering the reality of cultures predominantly exhibiting collectivism and high power distance, the call is made to acknowledge diverse concepts of peace.

The article aims to document the power and contribution of hibakusha’s stories and to analyze the cultural perspective of today’s peace studies.

ーーーーーーーーーーー

Part 1: The Power of Hibakusha Stories-Toshiko’s Story

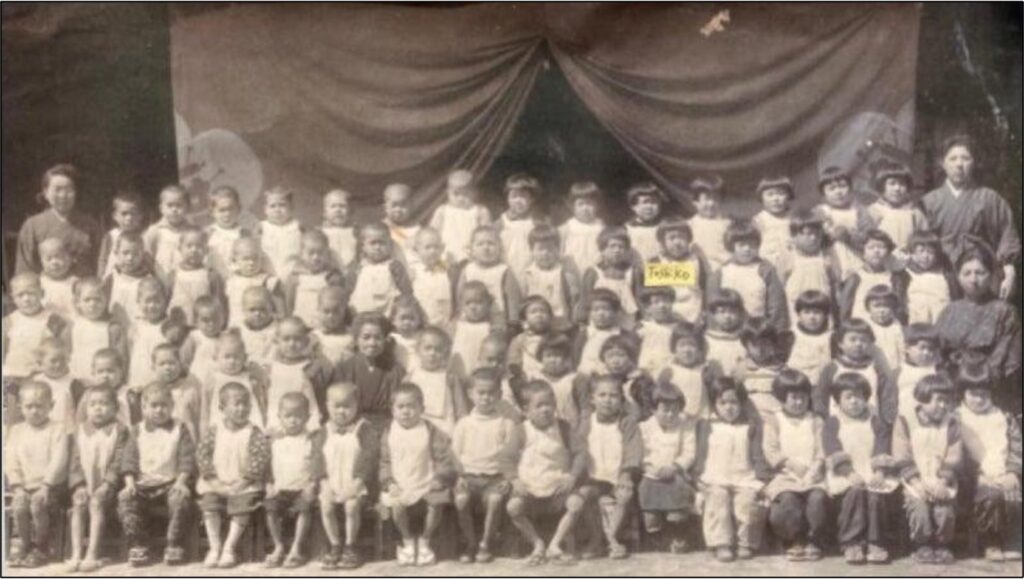

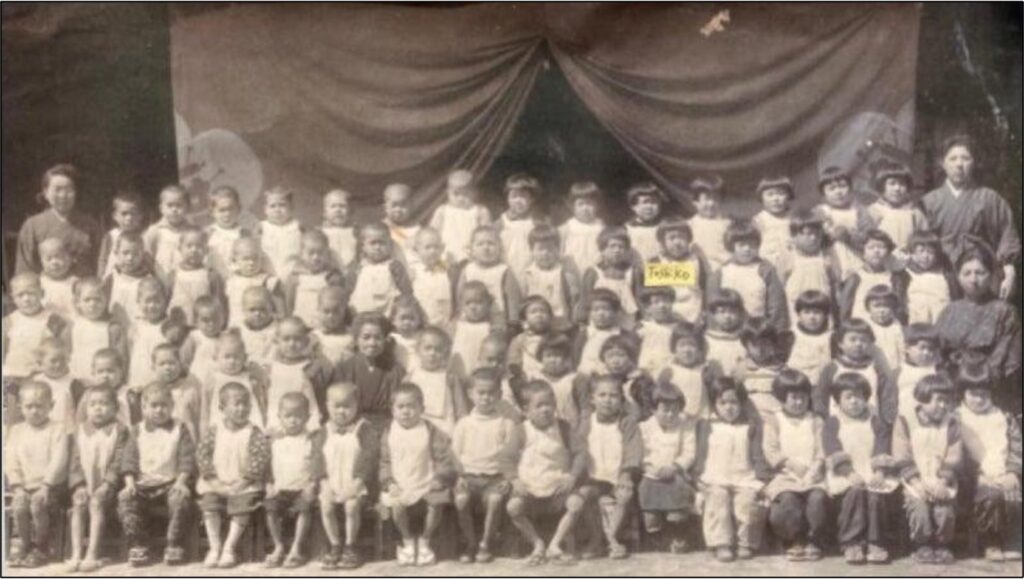

Graphics1: A graduation photo of Mutoku Kindergarten, Hiroshima, taken in March 1945 (Provided by Toshiko Tanaka)

Tragedy of Mutoku Kindergarten

This is a graduation photo from Mutoku Kindergarten in Hiroshima City, where the author’s mother, Toshiko Tanaka, attended. It was taken in March 1945. (Toshiko is the fifth child from the right in the fourth row, marked with a yellow note). The kindergarten was located at the site where the present-day Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum stands (Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward, Hiroshima). Five months after this photo was taken, Hiroshima was devastated by the dropping of an atomic bomb, resulting in the loss of countless lives.

At the time of the photo, Toshiko’s family lived in Kako-machi, Hiroshima City, about 1 kilometer from the hypocenter. However, due to the demolition of neighboring buildings by the authorities, the family was ordered to evacuate, and they moved to Ushita town in the present-day Higashi Ward (2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter) just one week before the atomic bomb was dropped. Consequently, although the family suffered extensive damage, they all survived. However, it is presumed that the survival of the children other than Toshiko, who would have likely attended nearby local elementary schools after graduating from Mutoku Kindergarten was bleak. The city of Hiroshima estimates that at 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, nearly 50% perished within the day. In areas closer to the hypocenter, an estimated 80-100% lost their lives. Tomonaga (2019) states a total of approximately 140,000 people in Hiroshima died instantaneously or within five months due to the atomic bombs, and the damage to the survivors’ health has continued to this day.

Memories of the Day of the Atomic Bombing

On the morning of August 6, 1945, at 8:15 AM, six-year-old Toshiko, a first grader, was waiting under a cherry blossom tree with her friends to go to school. It was a hot summer morning with a clear blue sky spread out above. As someone shouted, “Enemy plane!” and looked up at the sky, everything in front of Toshiko flashed white, and she couldn’t see anything. Acting quickly, she covered her face with her arms, resulting in burns to her right arm, head, and the back of her left neck. Even after 79 years, Toshiko vividly remembers the intense pain of the burns and the uncomfortable sensation of sand blown into her mouth by the blast.

That night, Toshiko developed a high fever and lost consciousness, but she recalls some memories from that day. Sometime after the atomic bomb was dropped, Toshiko witnessed a group of people moving silently like “ghosts” in front of her house. They were severely burned and had made their way from the epicenter to the outskirts seeking help. Many of them had burns so severe that they no longer looked human, with skin hanging from their fingertips as they reached out their arms. There were no longer any voices asking for help. Toshiko recalls the sight of them silently dying along the way was like a scene from hell.

Toshiko’s family tried their best to shelter the people fleeing from the epicenter in their partially destroyed home. Among them, Toshiko cannot forget about the two girls who were sisters. The 15-year-old elder sister arrived carrying her two-year-old sister, who had suffered severe burns. It is presumed that the elder sister took on a parental role after their parents perished in the atomic bombing. The elder sister appeared unharmed without any burns. However, it was later learned that the burned sister survived while the apparently unscathed elder sister had passed away. It is believed that she may have received a lethal dose of radiation. But at that time, people found this puzzling as they were unaware of the radiation effects caused by the atomic bomb.

Memories of Odors

When Toshiko miraculously regained consciousness several days later, the first thing she noticed was the intensely unpleasant “odor” reminiscent of burning rotten fish. She quickly realized it was the smell of bodies being cremated in parks and schoolyards throughout the town. Many hospitals and medical personnel were also affected by the atomic bombing, and survival depended on luck and resilience.

Damage from Radiation

From around the age of 12, Toshiko began to suffer from abnormal fatigue and swelling in her body, which led to a diagnosis of abnormal white blood cell levels. Radiation from the atomic bomb not only caused acute effects immediately after exposure but also continues to be a cause of long-term illnesses such as leukemia, other forms of cancer, and psychological damage, resulting in many people suffering even to this day (Tomonaga, 2019).

The story of “Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes” is based on the true story of Sadako Sasaki, who was exposed to the atomic bomb at the age of two and developed leukemia ten years later (see UNESCO Digital Library,1986). Despite suffering from symptoms, Sadako continued to fold paper cranes, believing in the Japanese tradition that folding a thousand cranes would grant her wish for recovery. However, her wish remained unfulfilled, and after eight months of battling the illness, she passed away at the age of 12. This story symbolizes the many individuals, like Sadako, who suffered from the aftermath of the bombings. It serves as a poignant reminder of the significant impact on civilians, particularly women and children.

Discrimination Against Hibakusha

Despite the economic development achieved in post-war Japan, discrimination against hibakusha was deeply ingrained in society. Toshiko recalls that in those days being a survivor of the atomic bomb was considered a “shame” that should not be openly discussed, leading many people to fear discrimination and maintain silence. Particularly due to concerns about the genetic effects on future children, women were avoided as marriage partners. Toshiko remembers a friend from high school who had a fiancé but whose severe keloid scars from the atomic bomb on her back led his family to oppose the marriage. The woman suffered a mental breakdown and remained single for the rest of her life.

Toshiko, blessed with two children (the author and younger brother) after marriage, had assumed her husband wouldn’t mind marrying a survivor like herself. However, when the author was born, her husband rushed to the hospital and anxiously counted the newborn’s fingers and toes. Only after confirming that the newborn was healthy did he express gratitude to his wife with a relieved expression. It was at that moment that Toshiko realized her husband had deeply feared the effects of radiation on their children. This story instilled in the author a sense of duty as a second-generation survivor to convey the threat of nuclear weapons to future generations.

The Wishes Embedded in Art

Until Toshiko turned 70, she never openly declared herself a hibakusha or engaged in testimonial activities. However, during her 45 years as an enamel mural artist, she had secretly incorporated symbols of peace, such as doves and the Atomic Bomb Dome, into her artworks. She explained, “I didn’t include these symbols to show to anyone else. I wanted to heal the trauma deep within myself by doing so.”

Toshiko’s works have been selected and awarded at exhibitions both domestically and internationally, establishing her as a renowned artist. In 1981, her artwork was presented to the late Pope John Paul II during his first visit to Hiroshima, representing the city’s commitment to peace.

Graphics 2:

Enamel mural work titled “Tree of Hiroshima” (180x90cm 1998) and Toshiko Tanaka: Approximately two months after the atomic bombing, a young Toshiko witnessed the bleached bones of a horse and a human side by side on the roadside, along with a small flower growing nearby. This scene serves as the motif for the artwork: the remains symbolize death and the flower the resilience of life emerging from death. Newspapers in those days claimed that no grass or trees would grow in Hiroshima and Nagasaki for 70 years. In reality, new shoots began to sprout from the scorched earth within a few months.

Testimonial Activities from Age 70

In 2008, at the age of 70, Toshiko embarked on a journey with Peace Boat, an international NGO based in Japan. At that time, she still felt uncertain about speaking out as a hibakusha. However, during a visit to Venezuela in South America, she was approached by a mayor who said, “Hibakusha have a duty to convey to people what happened due to the atomic bomb. If you don’t tell them, who will?” This prompted Toshiko to start actively engaging in testimonial activities both domestically and internationally. Over 15 years until the end of 2023, she circumnavigated the globe four times and conducted testimonial activities in approximately 80 countries. Her audience ranged from the general public, politicians, and international organizations to educational and research institutions, both domestically and abroad.

Peace Activism Through Art

As an enamel mural artist, Toshiko has participated in numerous projects related to peace education and advocacy through art. One example is the Garden for Peace project by NAJGA(North American Japanese Garden Association). Upon the request of the late Martin McKellar from the Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida, Toshiko designed the “Peace Ring” pattern, which has been depicted as sand patterns in Zen gardens across the United States every September since 2020, in conjunction with the International Day of Peace. This project, aimed at seeking peace, has shown a quiet expansion, and according to NAJGA’s official website, as of 2023, 27 gardens have participated in the project.

The Power of Stories

Toshiko’s support strongly impresses upon the author the “power of stories.” While Hibakusha shares numerous testimonies domestically and internationally, not everyone initially listens empathetically. Many people, especially in the United States, believe that “the atomic bombings ended the war” and justify the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Moreover, in Asian countries where wartime atrocities by the Japanese military occurred, solely emphasizing the atomic bomb’s damage may not open people’s hearts. However, the personal stories of Hibakusha, who lost their peaceful daily lives, awaken individuals to the shared threat of nuclear weapons, making them unable to remain indifferent. The author has witnessed firsthand how stories transcend historical and cultural differences, move people’s emotions, and bring about behavioral changes.

One project that particularly impresses the author as demonstrating the “power of stories” is their role in adopting the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons(TPNW) by the United Nations in 2017.

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), a coalition of NGOs, launched a global campaign to prohibit nuclear weapons under international law. Through their advocacy efforts, TPNW was adopted by a vote of 122 countries at the United Nations in 2017. Behind this achievement were the stories of survivors who worked alongside ICAN to lobby various governments and international organizations. ICAN was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize that same year. Setsuko Thurlow, who survived the Hiroshima bombing at the age of 13, concluded her Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech as follows:

“When I was a 13-year-old girl, trapped in the smouldering rubble, I kept pushing. I kept moving toward the light. And I survived. Our light now is the ban treaty. To all in this hall and all listening around the world, I repeat those words that I heard called to me in the ruins of Hiroshima: “Don’t give up! Keep pushing! See the light? Crawl towards it.”

The New Perspective Brought by Stories to a Palestinian Youth

As a final example of the power of stories, here is a case where a story brought new perspectives to the listeners.

In 2010, Toshiko was invited by the U.S. NGO Hibakusha Stories to testify at a public high school in the immigrant-rich district of Queens, New York. Among the audience was a young boy who had immigrated from Palestine. According to the teacher, he had endured a difficult childhood in Palestine, with relatives killed by the Israeli army. He had closed himself off to others even after moving to America. After hearing the atomic bomb testimony, he approached Toshiko with a question.

“I don’t understand. You suffered terrible burns and nearly lost your life because of the atomic bomb. All your classmates were killed. How can you forgive such a thing?”

Toshiko quietly responded to the boy.

“I, too, once hated America. But hatred only begets more hatred. Retaliation breeds retaliation. One day, I realized that we must break free from this ‘chain of hatred.’ … I want to continue living for the sake of my deceased classmates. As long as I am alive, I want to keep telling the world that they lived, that they existed.”

The boy stared at Toshiko, quietly listening. After this exchange, when asked by Kazuko Minamoto, who served as Toshiko’s interpreter, what he thought, the boy responded as follows.

“Before hearing Toshiko’s story, I couldn’t imagine a survivor forgiving America. My mind is still in turmoil and I can’t make sense of it… But I understand that there are perspectives like Toshiko-san’s.”

Several years later, Toshiko received a letter from the boy’s teacher. The letter stated, “as a result of that conversation, the boy underwent profound internal changes that surprised those around him, and he became more accepting of diverse perspectives.” This incident became a glimmer of hope for everyone involved, including the author, that violence, including nuclear weapons, might be reduced worldwide someday. Amidst the harsh realities in Gaza today, all we can do is sincerely hope that this Palestinian youth continues to hold onto “another perspective.”

Thoughts as a Second-Generation Hibakusha

The author’s emotional journey from perplexity to a sense of mission and solidarity, and finally to hope, supporting the activities of Hibakusha since 2008, can be subjectively described as follows:

Initially, the author harbored a sense of perplexity regarding speaking out as a second-generation Hibakusha until recently. It was questioned whether it was presumptuous to speak on behalf of those who directly experienced the bombing or who suffered and died as a result. Many second-generation survivors likely share this perplexity. The author once confided this uncertainty to MT, a second-generation survivor residing in New York who empathized with the same feelings. Even MT, who seemed to take a leading role in activities such as producing a documentary film about Hibakusha, shared the same doubts. This realization was quite surprising for the author.

Amidst the ongoing conflicts in the world and witnessing the unwavering dedication of the older generation advocating for nuclear disarmament until their final moments, the initial confusion of the second-generation survivors eventually transforms into a sense of duty to carry on their parent’s legacy. One second-generation survivor, upon learning about the Russian invasion of Ukraine, recalled his late father, who had shared his experiences through testimonies worldwide, even addressing 5,000 young Ukrainians in Crimea during the 1990s. Feeling that “the seeds of peace sown by my father are trembling,” he embarked on continuing his father’s legacy by engaging in testimonial activities. Stepping forward, second-generation hibakusha realize the presence of people worldwide who share their sentiments, leading to a sense of hope.

Suggestions for Making Hibakusha Testimonies Sustainable

The author would like to discuss the support needed to make A-bomb testimonies sustainable in the future. The average age of Hibakusha in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is now over 85. While the number of Hibakusha is drastically decreasing, the burden of testimony per person is dramatically increasing in proportion to the growing calls for the abolition of nuclear weapons. It is important to regard hibakusha as a “scarce resource for humanity” and to optimize the content of their activities by reducing their physical and mental burden as much as possible while confirming their wishes. Specifically, in addition to operational support (see note below), the digitalization of testimonies, which is already underway, and the promotion of the substitution of testimonies by those who have handed down their stories, the existence of a “manager” to optimize the quantity and content of activities is essential. The author would like to voice that elderly hibakusha tend to overwork themselves psychologically and physically to respond to the passionate requests for testimonies and interviews from all over the world.

Note: The operational support needed includes coordination with the source of the request, preparation of slide presentation materials, translation and interpretation, media relations, IT assistance, travel escort as a caregiver, and supplementary explanation of the actual situation of the atomic bombings. However, as already mentioned, what is more important is the management of the requested projects on behalf of the elderly hibakusha, including “accepting or not accepting” the requests.

Part 2: A Call for Many peaces

Norwegian peace scholar Johan Galtung, who laid the groundwork for peace studies, proposed the concept of “positive peace.” He coined the term “Negative Peace” for the previously common idea that peace is simply the absence of war (direct violence), believing that the opposite of peace is not “war” but “violence” itself. Galtung argued that humanity should strive not only for the Negative Peace of merely overcoming “direct violence” but also for addressing “structural violence” embedded in social structures such as hunger, oppression, and discrimination, as well as “cultural violence” that justifies these forms of violence. He advocated aiming towards a state where these three forms of violence are eliminated, known as “Positive Peace.”The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) defines Positive Peace as “the attitudes, institutions, and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies” – not merely the absence of violence or its fear.

In measuring the Positive Peace Index (PPI), which targets countries worldwide (163 countries in 2023), the IEP has identified the following eight empirically derived elements:

1. Well-functioning government

2. Sound business environment

3. Low levels of corruption

4. High levels of human capital

5. Free flow of information

6. Good relations with neighboring countries

7. Equitable distribution of resources

8. Acceptance of the rights of others

The top 10 countries in the 2022 PPI rankings were as follows:

1. Sweden

2. Denmark

3. Finland

4. Norway

5. Switzerland

6. Netherlands

7. Canada

8. Australia

9. Germany

10. Ireland

High individualism and low power distance observed in top PPI countries.

The Hofstede 6-Dimensional Model and Seven Worldviews (7WV) by Huib Wursten are utilized as tools for quantifying and visualizing cultures. Wursten combines Hofstede’s four cultural dimensions (Power Distance, Individualism, Uncertainty Avoidance, and Achievement (Masculinity)) to classify countries into seven cultural groups based on worldviews. Each Worldview shares commonalities in organizational structure and approaches to human relations, suggesting the presence of unique implicit worldviews.

Graphics 3: Huib Wursten, Mental Images and Nation-Building (2022), Culture Impact Journal

Result of the analysis of PPI Top countries (2022)

A high correlation between PPI ranking and individualism/low power distance is observed. All the top 10 countries belong to Western countries characterized by WVs with high individualism and low power distance. 5 of the 10 belong to the “Network” culture, with 3 “Contest” and two “Well-Oiled Machine” cultures.

The top 10 PPI countries (2022) according to 7 Worldviews:

– Network: Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Netherlands

– Contest: Canada, Australia, Ireland

– Well-Oiled Machine: Switzerland*, Germany

* Switzerland includes regions classified under the “Solar System” (French-speaking regions)

Expanding the ranking to the top 20 countries, 81% of the countries are classified under WV with individualism, and 67% under low power distance WV.

The Positive Peace Index has a high correlation with GDP per capita (IEP, 2022). This aligns with the following Hofstede’s statements on the correlation between individualism and a nation’s wealth (2010):

“We found that a country’s IDV (Individualism) score can be fairly accurately predicted from two factors…Wealth (GNI per capita at the time of the IBM surveys) explained not less than 71 % of the differences in IDV scores for the original fifty IBM countries.”

Hofstede also mentioned the correlation between individualism and power distance (2010):

“Many countries that score high on the power distance index score low on the individualism index, and vice versa. In other words, the two dimensions tend to be negatively correlated: large-power-distance countries are also likely to be more collectivist, and small-power-distance countries to be more individualist…”

:Positive Peace Report 2022- IEP

Using Hofstede’s Individualism and Power Distance scores, countries are roughly mapped into two groups (Graphics5): Western countries with high individualism and low power distance (egalitarian) which are located in the upper left quadrant, and the world’s majority countries with collectivist values and high power distance (hierarchical) which are located in the lower right quadrant. (The graph includes estimated scores).

Graph 5: generated by Hofsted’s Globe https://exhibition.geerthofstede.com/hofstedes-globe/

The former group of countries, characterized by high individualism and low power distance, leads the modern world in many aspects such as diplomacy, economy, and academia. And that is also where Peace studies and the idea of Positive Peace originated from. However, on a global scale, populations with such characteristics are rather a minority. It suggests that Western universalist concepts based on human rights, democracy, and market economies would be perceived as “foreign” to majority cultures. As Hofstede puts it,

“Respect for human rights as formulated by the United Nations is a luxury that wealthy countries can afford more easily than poor ones…The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other UN covenants were inspired by the value of the dominant powers at the time of their adoption, and these were individualistic.”

This suggests that when discussing peace, there may be insufficient attention paid to the values of the vast majority of the world’s population. For example, it is worth studying peace approaches based on the collectivistic/hierarchical side, such as those of Japan (ranked 12th in 2022 PPI, IDV 46, PDI 54), Singapore (ranked 14th in 2022 PPI, IDV 20, PDI 74), South Korea (ranked 19th in 2022 PPI, IDV 18, PDI 60), and Portugal (ranked 20th in 2022 PPI, IDV 27, PDI 63). Costa Rica abolished its permanent military and ranks 39th in the 2022 PPI ( IDV 15).

A Call for Many Peaces

Taga, in his introductory book to Peace Studies (2020), cited Wolfgang Dietrich, an Austrian peace and political scientist who warned that imposing the idea that “peace is singular” onto those who do not share the view is a form of “intellectual violence.” Dietrich argued that claiming one’s concept of peace as the only one leads to concealing inequalities such as economic disparities in the world. Even if the meaning of peace varies from one community to another, he believed it is not incompatible, and called for a dialogue about the various interpretations of peace.

“It would follow that specific forms of peace and of resistance against the capitalist world system should not be interfered with and that the idea of the one (perpetual) peace in the one world, as it is put down in all key documents of modern world politics, is, at least, sheer intellectual violence vis-a-vis those who cannot share this idea, because it is just this: an idea, put in front of man in order to conceal that not even this one is equal. The world, therefore, needs more than one peace for concrete societies and communities to be able to organise themselves.

The peaces do not become mutually compatible the moment everybody understands one another, but when all live in their own peace, that is, treat others like the members of their own kin, and so respect them even if they do not understand them. Let us look for our place and act in accordance with it! Let us talk about the many peaces!”

-Wolfgang Dietrich A Call for Many Peaces: Farewell to the One Peace

In the last paragraph of the book (2010), Hofstede emphasized the resonating idea with Dietrich that the only way to human survival is to accept cultural differences and coexist. If not, “any other road is a dead end. ” In the future, insights from cultural research (e.g., Wursten, 2023) will help us understand various concepts of peace and facilitate humanity’s coexistence.

CONCLUSION & DISCUSSION

In this article, the first part extensively discussed the story of a hibakusha and the societal transformations brought about by stories. In the latter part, a hypothesis is presented suggesting that mainstream concepts in today’s peace studies may be biased towards a single perspective of peace which is based on individualism and low power distance.

Future studies can explore the cultural diversity of notions of peace and approaches toward it.

REFERENCES:

ANT-Hiroshima. (n.d.). Toshiko Tanaka’s biography and activities. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://faces-hiroshima.com/en/toshiko-tanaka/

Hibakusha Stories. (n.d.). History of Hibakusha Stories Initiative. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://hibakushastories.org/history-of-hibakusha-stories-initiative/

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (3rd ed.).McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-166418-9.

Institute for Economics & Peace (2022). Positive Peace Report 2022. Retrieved from https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/PPR-2022-web.pdf

Minamoto, K. (2013). Kiseki wa Tsubasa ni Notte. (Miracles ride on the wings). Kodansha. ISBN:978-4-06-218405-2

North American Japanese Garden Association. (n.d.). Gardens For Peace. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://najga.org/gardensforpeace/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Americans, Japanese: Mutual Respect 70 Years After the End of WWII. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2015/04/07/americans-japanese-mutual-respect-70-years-after-the-end-of-wwii/

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. (2022). Yearbook 2022: World Nuclear Forces. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2022/10

Taga, H. (2020). Heiwagaku Nyumon 1 (Introduction to Peace Studies 1). ISBN 978-4-326-30289-5

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. (2024). 2024 Doomsday Clock Announcement: A moment of historic danger: It is still 90 seconds to midnight. Retrieved from https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/

The City of Hiroshima. (2022). Overview of Atomic Bomb Damage. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/soshiki/48/9400.html

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). (2024). Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.icanw.org/hiroshima_and_nagasaki_bombings

The Nobel Peace Prize. (2017). International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons Nobel Lecture. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2017/ican/lecture/

Tomonaga, M. (2019). The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: A Summary of the Human Consequences, 1945-2018, and Lessons for Homo sapiens to End the Nuclear Weapon Age. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 2(2), 491-517. DOI: 10.1080/25751654.2019.1681226

UNESCO. (1986). The UNESCO Courier: A Thousand Paper Cranes. Retrieved from

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000069680 U.S. Department of Defense. (2018). Nuclear Posture Review 2018. Retrieved from https://dod.defense.gov/News/Special-Reports/0218_npr/

Wursten, H. (2019). The 7 Mental Images of National Culture. Hofstede Insights. ISBN 9781687633347

Wursten, H. (2023). Culture and Geopolitics. Are we diverging?. Retrieved from https://culture-impact.net/culture-and-geopolitics-are-we-diverging/