National culture, Organizational culture and the issue

of values. “Is and Ought“

Blog by Huib Wursten and Fernando Lanzer

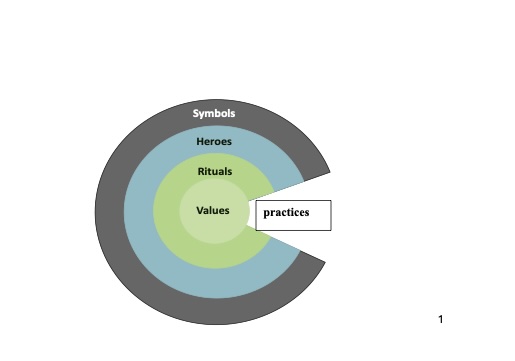

When it comes to culture, a common distinction is made between Values and Practices. Values are typically associated with national culture, while practices are more closely linked to organizational culture.

This distinction is expressed in the picture below

Fig 1: Hofstede’s culture onion

What made it confusing is that, in a widely known management model by Robert Waterman Jr and Tom Peters from the consulting firm McKinsey, the so-called 7-S framework the term “Shared values.” is included. This was also part of their best-selling book “In Search of Excellence,” published in 1982.

The McKinsey model consists of Structure, Strategy, Systems, Skills, Style, Staff, and Shared values.

They described shared values as defining an organization’s key beliefs and aspirations that formed the core of its corporate culture. Shared values were considered central because “they influence and shape the organization’s culture, impacting how individuals within the organization behave and make decisions.” In the McKinsey framework, “Shared values” was later referred to as “Super-ordinate Goals” and placed at the center of the model. It was clear that “Shared values” referred to aspirations (goals), rather than the underlying values described by Hofstede as being at the core of national culture.

Three years later, Edgar H. Schein published an article titled “Issues in Understanding and Changing Culture” in 1985. In it, he distinguished between what he called Artefacts, Espoused Values, and Underlying Assumptions. This model was included in his book “Organizational Culture and Leadership,” which became a classic reference.

Artefacts. These are observable phenomena like behavior and any overt, visible, describable aspects of the organization. They include branding and logos, office design and architecture, dress code, policies and tools.

Espoused values. Also visible to observers are the organization’s stated values and rules of behavior. It is how the members represent the organization both to themselves and to others. This is often expressed in official philosophies and public statements of identity, such as mission and vision statements, corporate values and codes of conduct. It can often be an aspiration for the future, of what the members hope to become. Trouble may arise if espoused values by leaders are not in line with the deeper tacit assumptions of the culture.

Underlying assumptions. These are unconscious, unspoken, hard to articulate (particularly from within) elements of the organization. They include the “real” but unspoken aim of the organization (to make the owner or shareholders wealthy? To serve the public? To create jobs?) and underlying beliefs about quality, speed, or safety.

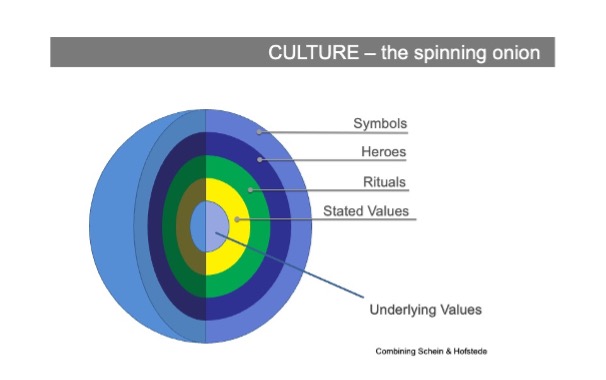

In 2017, Lanzer adapted Schein’s original illustration to include terms used by Hofstede in the “onion model”:

Fig 2: Schein’s model of organizational culture

Schein stated that the underlying assumptions of an organization give rise to the espoused values. The espoused values then drive people to create the organizational artifacts – which are, at the surface, easy to see and change. However, the underlying assumptions are the heart and soul, the undertone of the organization that we cannot easily see or determine – and if we want to change an organization, it is here, in the depths of organizational culture, that we must work. Shared tacit assumptions influence everything that happens in an organization, but they’re difficult to uncover and even more difficult to change. If we don’t discover or understand these underlying assumptions, any organizational change may not succeed anywhere other than at the surface level.

For effective management strategies, it is important to understand the difference between underlying values, as described by Hofstede, “shared values,” as discussed by McKinsey in their Organizational Management Framework, and the assumptions described by Schein at the organizational culture level.

| Hofstede Country Culture | Schein Organizational Culture | McKinsey Management Framework |

| Underlying values | Assumptions | |

| Country mottos, Constitution, Legislation | Stated Values(Corporate Values, Mission, Vision, Codes of Conduct) | Shared Values (Super-ordinate Goals) |

| Rituals | Artefacts | |

| Heroes | Artefacts | |

| Symbols | Artefacts | |

| Practices | Organizational Behavior | Behavior |

| Strategy, Structure, Systems, Skills, Style, and Staff |

In 2018, Lanzer proposed a picture to integrate the concepts introduced by Hofstede and by Schein: it was named a “spinning onion”, in three dimensions, to add the fact that the outer layers typically change much faster than the inner core. It is a known fact in physics that the linear velocity of a sphere is faster on the outside surface when compared to its core. In cultural terms, we know that the outer layers can change more easily and quickly compared to the core underlying values.

Fig 3: The Spinning Onion

In essence, it the difference among models describing country and organizational cultures is about the distinction between what the philosopher David Hume labeled as Is and Ought.

Country culture

Country culture is about CORE UNDERLYING VALUES.

The Hofstede dimensions of culture (Hofstede2001, Hofstede et al. 2010) represent a well-validated operationalization of differences between the cultures of present-day nations as manifested in dominant value systems.

The definition of culture: it is about the collective “programming” of the mind

that distinguishes one group or category of people from another.

“This definition stresses that culture is (1) a collective, not an individual attribute; (2) not directly visible but manifested in behaviors.

(3) about subconscious value preferences (4) shared by the majority of people in a certain country. We are talking about the preferences of most people most of the time.

The value dimensions and subsequent Worldviews are not a random collection of factors that emerge from a particular situation. Instead, they are validated through repeated research over more than 50 years.

Hofstede identified fundamental issues every society must cope with. So, what we call a cultural difference is determined by how the dominant majorities in a country address those issues.

The first four confirmed dimensions in Hofstede’s model (power distance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, and uncertainty avoidance) reflect those issues.

Each country has a ‘score’ on each dimension. These scores, in turn, provide a ‘picture of a country’s culture. Hofstede’s approach is clear, simple, and statistically valid.

Because of repeated research with matched samples, most countries’ scores are now charted.

The awareness is, however, growing that the scores on the four confirmed dimensions influence each other. Together, they lead to a “Gestalt “; the whole is more than the sum of the parts. In other words, the whole has ” properties” that cannot be reduced to properties of the parts; in the case of culture, the Gestalt takes the shape of a mental picture of what the world looks like, a worldview. Seven of these worldviews can be identified. For an overview of these

worldviews, see: Wursten H. https://culture-impact.net/cultural-dimensions-and-worldviews/

Research shows that core underlying values remain consistent over time—not to be confused with static! New situations arise, and the systems must adapt to the new environment. The adaptations are not happening from scratch. The shape is not random but steered by the rules of the game of the respective Worldview influencing each nation, community, or organization.

The 7 Seven Worldviews can be compared with the basic grammar of language systems.

Like in language, every basic grammar system allows different styles and dialects.

In our cultural discourse, organizational culture is about the dialects within the Seven Worldviews. The important observation here is that the dialects can only be fully understood by the grammar system to which they belong. In plain language, attempts to change organizational culture can only be successful if the changes are supported by the preferred values of the national culture to which they belong.

Organizational Culture, “Shared Values”, and Assumptions

We already referred to the McKinsey 7-S Framework. It was developed by McKinsey & Company in 1982 and was used to analyze and improve organizational effectiveness by examining seven interrelated elements within a company.

1. Strategy:

2. Structure:

3. Systems:

4. Skills:

5. Style:

6. Staff:

7. Shared Values

1. The meaning of the words “shared values”

The term “shared values” is confusing. The above clearly shows that the values (the subconscious preferences) are found on the level of the Hofstede dimensions and Worldviews. It is at this level also that we find what Schein called “Assumptions.”

The McKinsey “shared values “ are not about the existing programmed subconscious value preferences of employees. In other words, they are not about the “Is”. They are about the “Ought”: statements about the desired expected behavior of employees and the ambitions of the top management. They are better understood by concepts such as Mission and Vision: the way top management of organizations define the organization’s purpose and primary objectives. It answers the question, “Why do we exist?” The vision statement outlines the desired future state of the company, providing long-term direction and inspiration. It is also an expression of desired behavior by the employees. The employees are expected to comply with the desired behavior.

Practices

Focusing on practices, the first observation is that differences in practices are mostly predictable as a result of the type of business companies are involved in.

For example, because of the necessary coordination method in certain types of businesses.

Direct supervision is a necessity in uniformed forces (the Army, the Police, and Fire Brigades) as a coordination instrument. People who are attracted to this type of organization accept this, and it is also mainly a matter of self-selection that people choose to be part of it.

In the process industry it is a necessity to accept standardization as a coordination instrument. The specifications should not be open for interpretation. Again, it is a matter of self-selection that people who prefer to work in such an environment accept this and see it as a must.

In social work and in political organizations, the preferred coordination instrument is mutual adaptation.

Still, when comparing organizations within the same type of business, their organizational cultures can be very different. This is because the strong influence of the core underlying values of national culture are translated with different intensity and combined in a unique way for each organization by the leaders (at every hierarchical level) of each firm or institution.

Compliance

How do companies make sure their employees behave in compliance with the “stated values”?

Companies use a variety of strategies to ensure that their employees behave in compliance with value statements. These strategies often involve a combination of policy, training, accountability mechanisms, and a supportive culture.

Some common approaches:

Clear Policies and Statements:

- Formal Policies: Companies establish and communicate clear policies, outlining expectations and consequences for non-compliance.

- Code of Conduct: The principles are often included in the company’s code of conduct, which all employees are required to acknowledge and follow

Training and Education:

- Mandatory Training Programs: All employees are required to attend regular training sessions on the stated values. These programs may include workshops, online courses, and seminars to raise awareness and educate employees on the importance of the stated values.

Leadership and Role Modeling:

- Executive Commitment: Senior leaders demonstrate their commitment to the stated values through their actions and communication, setting a positive example for the rest of the organization.

Accountability and Reporting:

- Performance Metrics: Including the behavior that shows the stated goals in performance evaluations and linking them to compensation or bonuses for managers and executives.

- Regular Reporting: Tracking and reporting metrics, such as workforce demographics, hiring practices, and promotion rates, to ensure transparency and accountability.

Support Systems and Resources:

- Employee Resource Groups (ERGs): Supporting ERGs or affinity groups that provide a platform for underrepresented employees to share experiences and provide input on company policies.

Recruitment and Retention Practices:

- Focused Hiring Processes: Implementing structured and standardized hiring processes to ensure a candidate pool that reflects the stated values.

- Retention Programs: Creating mentorship, sponsorship, and career development programs aimed at supporting the growth and retention of people with the right fit.

Creating an Open Culture:

- Open Communication Channels: Encouraging open dialogue and providing safe channels for employees to report behavior not in line with the stated values bias without fear of retaliation.

Regular Assessments and Feedback:

- Surveys and Feedback Mechanisms: Regular employee surveys and focus groups are used to gauge the effectiveness of the stated values and gather feedback for continuous improvement.

- Third-Party Audits: Engaging external consultants to conduct audits and provide an unbiased assessment of the company’s DEI efforts.

By integrating these strategies, companies can create a work environment that not only complies with the stated values, but is also coherent with the core underlying values of the organizational culture.

0 Comments